Photo by Amelia J Dowd.

There’s a difference between occupying a seemingly unceasing parade of subject positions through a kind of colonising, thieving, dissipatory borderlessness … and inhabiting them as a form of aesthetic and political revolt. I mean, everyone knows what a fawn is. In this, we are united. But what even is a human these days? A gut-slumpingly simple and, yet, brain-turningly complex miscellany of randomly assembled particles tricked up in an array of increasingly hologrammatic and yet achingly real-feeling linguistic constructions?

Are we animals? Are we aliens? Are we feminists, Marxists, non-binary, male, female, transgender, black, white? Are we, as Brecht via Anne Boyer might have it, ‘constantly at work’? What are our sexual orientations? Do we eat meat? What would it be like to live in a world made entirely of plastic? What did our parents do to us to make us this way? Is it really all their fault? Or is pointing the finger at the people we love and need just another way we’ve come up with to turn the screws a little tighter on our bespoke off-the-rack self-torturing assemblages?

Speaking of torture, what is language, anymore, anyway? Turns out the correct usage of the word ‘myriad’ is now 500g of voyeur and a half-life of spider bite. Form of repressed two-minute noodle. Are the unlocatable truths of our dispositions more sinister now than language can call into being? Is that saucy? Because Elena Gomez’s Body of Work is poetry improv. This is never host a subordination without an exit clause. This is every funny and stupid and offensive and clever and meaningless moment you’ve encountered on the internet and / or in your life, selected, examined, dismantled and date-vaxxed with a tincture of tenderness cocktail before being reassembled as something more meaningful that we can all pay attention to. Preposition.

Not only is this Gomez’s way of saying, ‘it’s OK, you don’t need to worry about all of this, I’m going to worry about all of this, and I’m going to worry about it in a way that will hopefully cause you to think again about subalterns and diasporas and sex and genders and colonisation and capitalism and Marxism and all the post-human-isms. Because I am’. Meanwhile. As a reader, I am capital (possibly), a household object with a point of view. Gomez continues. Not, or not only … Because the situation demands it, but … Because I demand of these situations that you, as yet, have no way of thinking. That they include me. Eye, E. Words are not stones. Or, are they not? Jumpsuits would have genitals if they could remember what they are.

Am I right? No longer possible to position oneself as Kafka-esque in response to a world in which one is neither dreaming nor sleeping, but into which one is somehow continuously being plugged. A Gomez poem walks up to a gatekeeper in a bar, ‘It’s not I don’t care but terrible / sentences for why,’ it says. The ongoing nightmare of multiconcatenous surfaces made bearable through the insubordination of what? ‘Forget the forgetting of forgetting,’ a well-known interview broadcast from a world-famous streaming service, the notorious talk show host recently remarked. ‘Do you think I’m as stupid as I look?’ To which the infamous improv specialist instantly replied: ‘How could that be possible?’

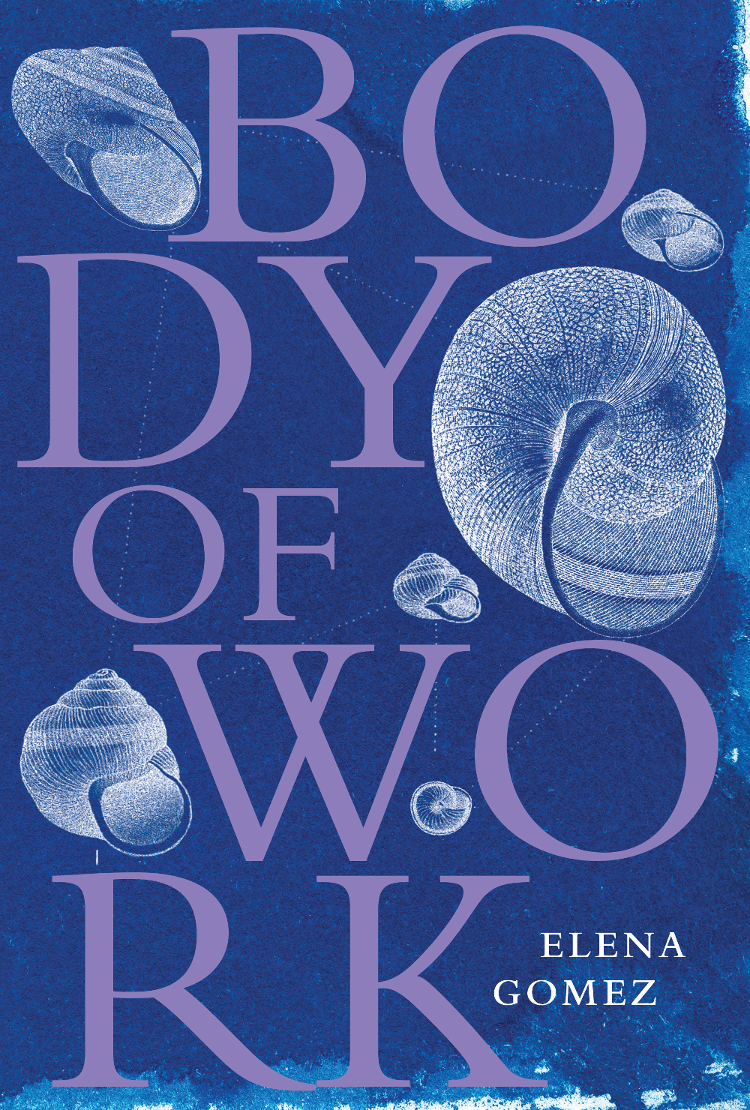

Cover design by Zoë Sadokierski