I thought 'Well, fuck everybody' and wrote the book I wanted to write.

The second-last day of winter in 1997 seems so far away now, but today I remember it clearly. After her captivating late afternoon reading, Dorothy Porter and I found a corner in the dining room at the Varuna Writers' Centre, Katoomba, the daylight waning outside amidst steely dampness and the trickling departure of friends.

I was but a young whipper-snapper and Dorothy had happily agreed to be interviewed for the third issue of Cordite. We'd just launched a selection from What a Piece of Work as the 9th Varuna New Poetry broadsheet, had no doubt enjoyed a couple of glasses of wine and were both keen to talk.

Today has turned similarly grey, a southerly wind driving drizzle from the sea into the city. That distant evening, over a decade past, feels very close, and time seems darkly sympathetic.

I last saw Dorothy in Darwin at the Wordstorm Festival in May this year. The first day we ran into one another in the hotel lobby, waited for our lift out the front, getting into the temporal elasticity of the tropics, catching up with where we'd been and what we were up to.

The next day we decided to walk, joking through the interminable humidity about how our amusingly confident senses of direction led us invariably astray into unexpected but nevertheless interesting places. We said goodbye under a tree after she read from El Dorado – 'water is a gorgeous lulling aqua -. it has always known I was on my way' – the Arafura sparkling in the near distance.

She urged me to check out the natural history museum and art gallery just up the hill, especially for the snakes – 'to me, snakes are sacred, treat them with respect' – and I went there.

I feel that the following interview grasps, however anything could possibly grasp such fleeting but enduring things, something of Dorothy's disarming vitality and no-bullshit honesty, her determination to 'live life as an epiphany' and, in the spirit of Frank O'Hara, her facility to just 'go on her nerve'.

I contacted David Prater this afternoon and he very kindly agreed to re-post it, a second incarnation after its first appearance way back in 1998. Dorothy was such a friend and mentor to so many writers, I thought it might catalyse in Cordite a space in which people can respond and send in their own memories and stories of Dorothy – a memorial of sorts.

Not that such a thing is necessary, given the poetry itself, but it at least feels right to share something of our grief and our memory of a woman and a poet whose neurons were abuzz.

Peter Minter, December 10, 2008

“Poetry's Like Sex – You Can't Fake It”

Peter Minter: I'd like to begin by discussing your earliest experiences of writing. When did you start writing poetry, and what initially motivated you?

Peter Minter: I'd like to begin by discussing your earliest experiences of writing. When did you start writing poetry, and what initially motivated you?

Dorothy Porter: I didn't really see myself as a poet until I was about sixteen, although I did start writing when I was about eight – writing stories and making little books. It wasn't really until the age of about sixteen that I began to see myself as a poet. I came to poetry via music, particularly the rock music of the late sixties, the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane, the late Beatles. It was an extraordinary time, a ferment.

I was 14 in 1968, which was an incredible year, and 16 in 1970, which is when I started taking myself seriously as a poet. That's when I started reading Poetry, not just the stuff at school. I was reading the usual things, in a critical sense, like Shakespeare and Keats, but at one time there was a poem by Ted Hughes called 'The Wind' that really struck me. Much more dramatic though was seeing William Carlos William's 'The Red Wheelbarrow' written on a blackboard. A friend of mine was at a progressive school with a groovy English teacher, who was a poet himself, and he wrote this poem on the board. I'd never seen a poem like that before, although now when I think of the content I'm amazed that it even appealed to me, but I just felt this extraordinary sense of possibility in its clarity and focus and short lines. So I started writing these short lines, a la William Carlos Williams.

That was a key thing, and at the same time I was trying to use the beat and passion of the things that were happening in music, to replicate those into what I was writing. Prose seemed unsatisfactory. I was writing these rather 19th century-esque, episodic novels about my friends at school, and I think the music 'upped-the-ante' of my emotional experience without me even knowing it. It was a very exciting time, even though I was just at school. I wasn't marching in any moratoriums.

So when did you start publishing your work?

I got to university, met like minded people, and had my first poem published when I was nineteen in the Saturday Poetry Bookclub, something Rae Desmond Jones and Joanne Burns were associated with. That was in 1973. Then I was involved in the Sydney University Poetry Society and I met Robert Adamson and other poets. Things escalated from there.

You had many early poems published in New Poetry. It's interesting that, with regard to the comments you make about the influence of American music, a great deal of the work published in New Poetry was influenced to some degree by American poetics. Was this something that you found happening with your own work as well?

To a certain extent, yes. Perhaps not as self consciously and as deliberately as some of the other writers at the time. It's not how I am.

I imagine you may have read a number of the postmodern American poets.

Well, I was hanging out with people like Robert Adamson and the young Chris Edwards, who gave me that Donald Allen book of American poetics (The New American Poetry) as a present, and I remember reading Duncan and the idea of the poem as a field, and things by Charles Olson…

Do you feel that reading that work, the ideas engaged with by those poets, were a direct influence on you?

Yes, I think they were, but again I'm always a person who has gone my own way, for good or ill. I'm not a cliquey, 'join-the-group' sort of girl!

Were there other US poets who were important to you then?

I think when I was older Frank O'Hara was a much more profound influence. I liked Robert Duncan's sense of the occult and the sacred, and was perhaps rather pretentiously interested in those things too, and I still am, though now in a much more meaningful way than when I was younger. I liked the sense of possibility in what they were doing, breaking all the old rules.

Frank O'Hara's voice seems to be present in your first collection, Little Hoodlum Were you reading him during that time?

I don't know if I was reading him that early, but I certainly was later on. I love his work, the warmth and intimacy, his sexuality. His poems are sometimes complex and opaque, and verbally challenging, but they're fun and, to be honest, I hate heavy, pretentious 'boys' poetry.

It's interesting that you make that comment, because you do use explicit, straighforward language, which is also present in O'Hara's poems, to balance the heavier, mythic or psychological density of your later work.

Like O'Hara, I go on my nerve. He pointed out the way in his wonderful manifesto on Personism. I like his campness and subversiveness, and the fact that, while he has a lightness of touch and an urbanity, he is not an academic poet. These are all things that did influence me, just as they did quite a number of people. But I think the question of influence is always a personal thing, its got to become part of you on an intuitive rather than a simply popular level.

But myth and psychological density are important to you as well?

I think its not something I'm self-consciously aware of, it's just part of the many things I'm interested in. I have an enormous curiosity and those aspects of my work are part of my very foggy but intensely spiritual sense of things, which are not a function of a materialistic or rational desire to make sense of life, but more to be part of things, to 'live life as an epiphany'. And myth is so rich. I like mythic stories – I'm a poet who reads a lot of novels and a lot of stories, and still the most extraordinary stories are told in myth. In fact, I think one the most powerful books I've read in the last couple of years, without a doubt, is Ovid's Metamorphoses. I'd only read it in snippets before, and it's about a lot more than beautiful young things changing into trees. One of the strong motifs throughout the work is the violence of incest, and lust and frustration. The stories are just unbelievably affective.

Such stories are a strong part of Akhenaten, and in other ways The Monkey's Mask. In what way are you interpreting the poetics and myth-making of poets like Ovid or Duncan?

I suppose I'm trying to compost them and assimilate them. Like a lot of writers I'm a magpie or thief more than an intellectual, and I don't think my approach is just cerebral. I work off what gives me a buzz and what doesn't. And when something gives me a buzz, whether its Ovid or whether its 'Piece of My Heart' by Janis Joplin, something will happen. I wait for my neurones to buzz.

Which is an interesting idea in itself, when some contemporary ideas about poetics prioritise linguistic models or theories within the process of writing. What you have just suggested is that you work more from an emotional, non-intellectual response to your material.

Absolutely. I agree with Ezra Pound that only emotion endures. I've got a problem with a lot of stuff that's theory driven. I think it can end up an incredible wank, and can back itself into a corner. And poetry has been backed into such a corner this century, so I think its time to turn it. I'm just interested in what endures.

So who are the poets that endure? I've heard you're quite interested in the Modern Russian poets.

Yes, particularly the two girls, Anna Akhmatova and Marina Tsvetaeva, and the two boys, Boris Pasternak and Osip Mandelstam. I've read them in translation. Then there's the gay poets, like Lorca or Cavafy. I've also learnt a lot from poets like Elizabeth Bishop, even though she and I are very different.

When you say you've learnt a lot from other poets, how do you respond to them? You've said that you're hesitant about engaging with theoretically based poetry, so what is it in your craft, as a material approach, that helps you 'make' this difference between an emotionally-based and an intellectually-based poem?

I trained as an actor and I always look at what works. Of course what works is a very subjective thing. And I do like some difficult poetry that could be seen as more theoretical than emotional, because I like a wide range of different poetries. But I don't pretend to myself that I like something when I don't. Poetry's like sex – you can't fake an orgasm. And some poetry I fancy and some I don't. It's like Frank O'Hara's joke about making jeans so tight people will want to go to bed with you. There are some poems I don't want to go to bed with, and there's some poems I do. I like clarity, I like honesty, I like pizzazz, I like passion, I like a pungent use of colloquial language. There's all sorts of 'ingredients' that appeal to me.

So was the experience of having had a lot of your initial publications in New Poetry, where a lot of those qualities were part of the poetic, important in the establishment of your own sense of voice?

Of course. It was terrific. It raised my confidence and I felt part of an exciting community of poets. It was a very exciting time, but it passed.

So how did you deal with the boredom of the eighties?

With great difficulty! It was a hard time, although that's when I wrote Akhenaten. The eighties were a hard time for me, but I look back, like Moses, and know that I needed to spend that time in the wilderness or I wouldn't have written Akhenaten, which was a seminal book for me.

For what reason?

Because I did what I wanted to do. The things I'd wanted to do finally came together in Akhenaten. I'd wanted to write a long narrative poem, and I'd wanted to explore things like gender, sexuality and history. Akhenaten's about everything. But I was nowhere near the centre of the poetry scene at that time, living in a house in the Blue Mountains, isolated, feeling neglected, bitter and pissed off. I know a lot of people see my career just in terms of the last few years, following The Monkey's Mask, but I've been around for a bloody long time, and during most of this time I've been ignored. So I'm enjoying it now, but I've had a long time in the wilderness, and in the wilderness I thought 'Well, fuck everybody' and wrote the book I wanted to write. I think that would be helpful to a lot of poets who only have their eye on the market, or their eye only on what's happening overseas. The irony is that, even though poetry's in desperate straits at the moment, a huge amount of poetry is published, and although I've seen packed poetry readings we have to ask why aren't people buying books of poetry?

Was the verse-novel style of The Monkey's Mask your way to help overcome this?

Yes. To my amazement that book seemed to leap across the flames.

Following the initial period, then, with New Poetry and the seventies and the eighties, some kind of shift happened for you around the experience of writing Akhenaten.

Yes, for the first time I did what I really wanted to do. I wanted to really go for it, not write the usual one page poem, because I wanted to write about everything…

It appears that you wanted to reject the aesthetic confines of the single-page literary journal poem.

Yes! I wanted to write something exotic and exciting. I was reading a lot of Cavafy, and I thought 'I want to write a book that's absolutely yummy,' something I'd want to read that wouldn't be a chore. And I threw everything into it, the whole shebang. I had nothing to lose. And part of me is kind of nostalgic for that time, because I had the freedom to do that. So I honestly wish sometimes that some poets would go away and say 'Fuck it!' and write the book they want to write.

Do you feel that you can't do that now?

I think poets are losing their nerve. There's too much a sense of what one should be writing for the market, the critical or reading markets, the big boy poets one should flatter with a book. There's a sense of people without much nerve. I'm just longing for poetry with verve and nerve, even if I don't really like it that much. I'm longing for poetry that just smacks me across the head.

Is that something you find happens often? I mean, who are you reading now you would consider energetic or important?

It doesn't happen enough. When I calm down and listen I know that we do have some very good poets. I've just finished Peter Boyle's book, The Blue Cloud of Crying, which is passionate and political. And his influences are different. They're not just the tired old Americans.

A more classical, European feel. Very unlike the Language Poets, for example.

That's right. To me Language Poetry is a poetry of a safe democracy, very much a middle class poetry, where nothing much is happening in life – being so comfortable one has to make something up. It's academic and dreary. Plenty of people disagree with me and that's fine. But I do see theoretical poetry as something fin-de-siecle. It's a poetry of lassitude, of decrepitude and fatigue. And what I found exciting about Peter Boyle's book is that, although there's some things I might disagree with, he was confronting me with things, and taking things seriously. I have a great respect for him after reading that book.

So you don't feel that Language Poetry and the theoretical project it assumes has helped free-up the use of poetic language?

Well, I haven't seen it do that yet, it's too dull. I think the language of music and the language of the streets, the rhythms of colloquial speech, are much more interesting, much more revolutionary than a bunch of blokes staring up their bottoms at universities. To me meaning is important, and I think its easy to make a virtue out of something you're not good at. It's interesting how people might eschew meaning or narrative, but they don't really know what they're doing themselves. It's also hard to evaluate poetry which becomes a form of esoteric nonsense.

Why do see it as nonsense?

I think it can end up a kind of meaningless babel. It has absolutely no appeal to me at all.

Something that has interested me about your work is that rather than assuming certain competencies of a particular readership, you appear to purposefully make your poetry broadly accessible.

But then some of my stunts are informed by postmodernism as well. The genre crossing of The Monkey's Mask is a postmodern cliche, as was its non-privileging of high culture over pop.

How did you negotiate that, from the position of being or playing 'the Poet'?

Well, this is where I'll mention a name that is going to make most people fall over in horror, Camille Paglia, who I disagree with profoundly on a lot of things, but who is a passionate advocate of popular culture. And so am I. Again, I'm a passionate advocate of anything with energy, and this leveling of assumptions is a great thing about postmodernism. Of course it can be made absurd. To my mind, Tolstoy is better than Jacqueline Susan, although a purist, fundamentalist postmodernist would disagree. I believe in literature, but also in flexibility, movement. I don't want to be in an anaerobic environment, and the oxygen is in pop culture. It might be ephemeral and fizzy, but it's alive.

A friend once said an amazing thing, that one of the greatest things that will be remembered about the twentieth century will be Black American music – jazz, soul, the blues and rock 'n' roll. In fact any skills I have in performance as a poet I've learnt from singers. From listening to Billie Holiday I've learnt that phrasing is crucial to both singing and poetry, but a lot of people don't seem to have any respect for the art of performance and reading, perhaps because for many poets its all in the head and they don't seem to remember its an art with a history that goes back a very long way. It can be a kind of arrogance thinking that you and your mates invented it.

I'm interested in your ideas about phrasing. Is this something you're aware of as you're actually writing?

It can be, yes. All sorts of different things happen when I'm writing. There's different speeds in the way things happen. For example, I can write some poems that are terrible, that are just a mood thing and might stay between me and another person, or as part of a journal or nothingness. Others are part of a big project. And some come from nowhere, and are good.

Are you aware of that differentiation before or while you're writing, or once you've finished something?

I think I write at my best when what I'm writing is part of a larger canvas, when I'm working on a tapestry. This might be a female thing, but it is a bit of a theme to the way I work, stitching away and aware of a bigger picture. I'm no longer much of a poet for feeling 'Oh, I think I'll sit down today and write a poem.'

Is this something that has happened since Akhenaten, engaging with the larger mythic stories?

Yes, I think so. I've just written four poems after I went to the Northern Territory, but even these were very much part of a larger canvas. I do try and write one-off poems, when I get the right mood or feeling or I hear or see something, but usually they're relatively mediocre, lyrical pieces. And I'm fascinated with myth. For example, I think that the Minoans are part of our unacknowledged heritage, and we have trouble coming to grips with this because they were so wild and irrational, sexual and female and amoral. But the Minoans were very realistic, because unlike us they weren't particularly phased by death. They didn't really feel there was much of a division between being alive and being dead.

How would you describe your interaction with that?

Basically it's a magnet. I get pulled towards those things, and I want to explore them and take them through my nervous system and see what happens.

Does the poetry arrive as an eruption on the boundaries of these ideas?

Sometimes it can start as an eruption, an emotional reaction or inspiration, but then it becomes much more intellectual for me. I feel great during the inspirational process. That's a kind of demonic writing, without any editing at first. I then I have to play with it. Like when I wrote 'Exuberance of Bloody Hands', the first poem of the second section of the 'Crete' sequence, it happens very quickly.

The 'Crete' sequence is quite demanding, in an intellectual sense, but its suffused with feeling. It demands a lot of readers in that it requires background knowledge, and the poems make a lot of weird juxtapositions and jump and leap. They're clearly written, but I think it was one of the hardest books to write.

Which women poets would you see as antecedents to what your doing now?

Definitely Emily Dickinson, who is one of those amazing, inexhaustible poets. Her range is fantastic, and the condensation in her language is almost like a form of nuclear energy. I find her a very challenging, almost scary poet.

It's interesting that you bring up the idea of condensation, because a lot of your language, and your use of the line, are very condensed.

My teachers there are eastern poets, but as I get older and crankier I don't have the patience anymore for bullshit. If someone asks me to wade through something difficult and obscure it better be worth it! Life's short. So if as a reader I can reduce a complex, self indulgent rave into something that's basically very simple, I get quite angry.

Apart from Dickinson, what other sources might you be effected by?

Well, in The Monkey's Mask there's a huge amount of Basho, which might sound extremely surprising, but he's important in that condensation of lines, that sense of the moment. He was in many ways the father of Zen in Japan, one of their preeminent poets. The title of my book comes from a late Basho haiku, and I got the idea of writing The Monkey's Mask when I was doing creative writing workshops in prisons, in Long Bay gaol. I was teaching haiku, and one guy said 'You could write a detective novel in haiku.' At first I thought he was just taking the mickey, but later I thought he was absolutely right! Those moments of revelation, in the present tense with the senses working moment to moment to moment, that acute awareness, are when detective fiction is at its most interesting. This is very close to poetry. Raymond Chandler was a failed poet who then went to crime fiction, and his books work much more on a poetic level than a pop level – their image, tone and mood, and his fantastic use of language. They're virtually prose poems in some ways. Of course I didn't attempt to write The Monkey's Mask in haiku, although I think linked haiku can go on forever and do all sorts of things, but it gave me the idea that each poem could be very, very intense, and the reader would feel physically in a particular moment. So Basho is important to me.

Another writer would be Dorothy Parker, who wrote those sharp, short, bittersweet throwaway poems, which are fantastic. And Catallus, the Latin poet – 'I hate and I love.'

That's a fascinating aesthetic you're describing. A lot of work since the seventies has elevated the elaboration of ideas, via an attraction to the poetics of 'the long poem', whereas you seem to be undercutting that approach on the level of each individual poem while placing them in extended series.

It's got a lot to do with me and my boredom threshold. The poems I enjoy cut to the chase. I want to write poems that I enjoy reading. I think poets should ask themselves whether they enjoy their own work, and if they don't, ask themselves why not, am I boring myself as well as others?

You appear to enjoy performing your work too.

Yes, I do. It's hard presenting new work, but when I have poems and I know how they click, it's like getting up and singing a song. It's a buzz.

To move on, can you tell me something of where your is work heading now?

One of the big themes of writing The Monkey's Mask was Poetry, and one of the big themes in my next collection, What A Piece of Work, is The Artist. One of the main protagonists, a psychiatrist, sees himself as an artist with the ultimate materials, other people's brains and souls. He can make his own creations.

Why did you choose to write on someone like that?

On a coarse level, I have a certain Gothic, ghoulish interest in the madhouse and the people who work in such places. On a more sophisticated level I'm interested in the mind as something material that can be played with. There's a wonderful line in Hamlet, when Hamlet's talking to Rosencrantz and Gildenstein and he says something like 'you might fret me but you can't play me', meaning he is not a recorder they could play. This brings up both a sense of his integrity, and of how fragile a mind can be.

One of the main characters in What A Piece of Work is Frank. Where did he come from?

The starting point for Frank was Francis Webb, but I left him behind and have created an entirely fictional character. He's very little like Francis Webb.

But in a sense he is an ideal starting point for a critique of the assumptions built into the trope of tortured, Romantic artist. He posseses a lot of credibility in Australian poetry, but also represents some of those traditional assumptions about poets and poetry.

Yes, the mad genius. My character Frank is a kind of deconstruction of the mad genius, and at the same time I've made him a human and sympathetic character. Its a very humanistic position, but I've not made him a sentimental character. I didn't want cute madness – he is really mad, and suffering, because he is mentally ill. In the early stages of the book the psychiatrist is genuinely trying to alleviate that, even though later on he doesn't care at all. And despite Frank's frailty, he also has strength and dignity. That's part of my creation, I've created a man who is gifted, mentally ill and in an institution where he is absolutely vulnerable.

This is a big shift from The Monkey's Mask, where your representation of the body was situated in discourses of gender and sexuality. Frank's body is the subject of very different frames.

Yes, he has no control over what happens to him. In The Monkey's Mask Jill suffers an extraordinary and very potent sexual infatuation. So does Mickey. But the point there was that one has a choice in such things, and it can be fun going to hell and back. Frank doesn't have that choice, while in The Monkey's Mask they're embracing it. Frank's struggling to function, to write his poems and survive in a hideous environment, to negotiate to have his space and writing materials. In a psychiatric institution these things are privileges, not rights. His body is often subject to extraordinary therapies, not all of which he consents to.

So in many ways Frank's subjectivity is taken over, or blurred by discourses of medical knowledge and psychiatric practices. Is this unlike the representations of subjectivity you write into your earlier books?

Yes. His is not a sexual subjectivity. He's not in any way moved by sexual desire, and in fact he is entirely isolated from that. It's his mind and his tentative grasp on his art that counts.

Frank's persona is something very new to your ouvre. Why are you using such a figure?

Well, I haven't really thought about this, so I'm thinking on my feet here. I've always been interested in poets and extremists, and I'm aware that poetry has become so comfortable, with no sense of urgency. A lot of poets live out all that false Romantic bullshit. And the important thing about Frank is that he hasn't chosen some sort of groovy option or lifestyle, and yet he's writing poems.

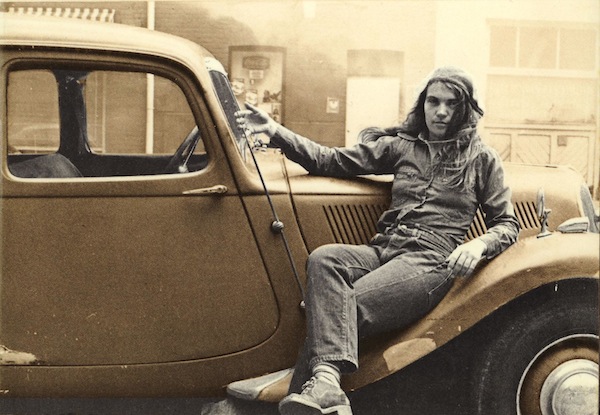

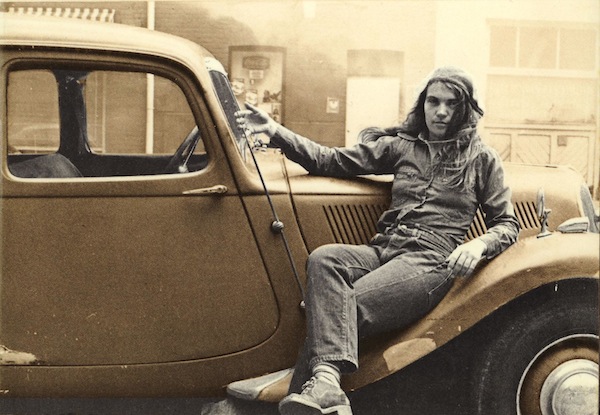

This interview was originally published in Cordite#3 (1998). Issues #1 through to #5 are available for download as PDFs. The image is a detail from the front cover of Dorothy Porter's Little Hoodlum (1975). Original photo by Kay Whitehead.