It may seem that only the Mordue and Whitelock poems have a political edge in explicitly holding the government and people at large to account, but writing testifying threat and trauma resulting from neoliberal, late-stage capitalism is intrinsically political if we accept that these are not natural disasters so much as human-induced crises. Such writing contributes twofold: first, as a mode of linguistic-affective record of lived experience from within collective crisis, and second as a challenge to the institutionalised denial and minimisation that enables the continuation of high-risk practices in the face of ample evidence against them. These texts might not have the power to stop ruinous trajectories, but they can help us make sense of our experience, offer solace, and help nurture the united resilience needed to demand urgently needed change.

It is important to note that social media platforms are increasingly a forum for the self-publication of writers, opening up new modes of writing and reading. Jodie Nicotra has challenged outmoded perceptions that limit writing as ‘linear, essayistic, and the province of a single author’ (W259). Insisting that these old school notions of authorship are outdated, Nicotra coins the term ‘Folksonomy’ to describe writing that involves ‘dynamic, newly spatialized practices of composition occurring on and via the Web’ (W259). Nicotra calls for a new metaphorical understanding that situates writing as the ‘building of a space rather than the production of a text’ (W263). Social media, as a prime space-building zone, not only to disseminates writing directly to followers and readers but potentially builds affectively charged spaces of solidarity.

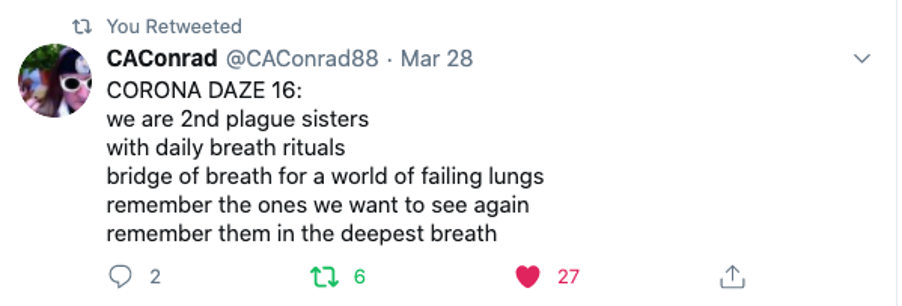

The American poet CAConrad, known for their (Soma)tic poetry experiments, tweeted short poems throughout 2020 in response to COVID-19. The following poem melds the historical trauma of HIV/AIDS memorial with the fresh threat-trauma of the COVID-19 pandemic:

Figure 1 (2020)

As seen in Figure 1, Conrad reminds us that the current pandemic ‘we’re all in it together’ rhetoric resounds bitterly with a surviving queer community that remembers all too clearly the discrimination, persecution, tragic losses, and hard-won gains of the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

Though short, this poem packs a punch, inviting keen affective and empathic resonances and solidarities. Anna Gibbs and Maria Angel have argued that ‘digital environments have a strong relationship to gestural, sensory and affective modes of communication’ because they appeal ‘to the senses and sensory novelty’ (para 5). On Twitter, for example, tweets can be surrounded by paratext such as hashtags, linking the tweet into a broader conversation. We read a tweet, and can engage directly with a conversation, sometimes in real-time. Tweets can include visual elements, such as photos, gifs, or videos. In the case of Conrad’s poem, there is no paratext other than the title, ‘CORONA DAZE 16,’ and there are no visuals apart from the profile pic, which confirms the queer identity of the poet. Gibbs and Angel also state that ‘electronic works solicit the body’s involvement with reading via gesture’ (para 20), and my retweet of ‘CORONA DAZE 16’ stands as evidence of this. Moved by and impressed with the poem, I made use of the platform affordance to share it, and this bodily impulse has given rise to the phenomenon of writing going ‘viral,’ for better and for worse. Rhythm, Gibbs maintains, is central to the work of resonance. It is a way of ‘attuning to vitality forms that suffuse the present, without being entirely subsumed by them’ (‘Writing as Method’ 233). This process is, she argues, most evident in poetry as the mode of discourse closest to the body, (233). The body – individual, social, and historical – and breath and rhythm are front and centre in this poem, which is essentially an act of solidarity and an elegy testifying to the way the present threat and trauma (the COVID-19 pandemic) triggers past threat and trauma (the AIDS pandemic).

For Thomas Fararo and Patrick Doreian (1998), solidarity is a construct of social phenomena that comes into being by way of an empathic alignment and a sense of shared identity within a contained group dedicated to attending to mutual needs. Sociologist David R. Heise (1998) has argued that specific events induce empathic solidarity, described as a type of solidarity that involves a bond forged by affective resonances between individuals that motivate actions of an alliance. Retweeting a poem like Conrad’s proclaims alliance. A social injustice-crisis creates heightened conditions for empathic solidarity. This raises the prospect of technologically mediated writer/reader/textual empathic solidarities as a unique mode of contemporary trauma witnessing and testimony.

Another characteristic of this writing, which most of the featured poems share, is implied moral injury. In clinical trauma studies moral injury refers to the residual impact of traumatic situations that force individuals to perpetrate, witness, have knowledge of, or fail to prevent ‘acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations’ (Litz et al., 697). The poems express and mirror the sense of moral injury many now experience. Psychiatric researchers have correlated exposure to morally injurious events to the onset of PTSD and other post-traumatic reactions, observing pernicious feelings of ‘guilt, shame, anger or embitterment related to the nature of the moral injury’ in some demographics, such as military personnel (Steel & Hilbrink 16). While it would be questionable to suggest writers at large and the general population suffer the acute form of moral injury outlined by researchers studying wartime scenarios and other extreme human rights violations, it is possible there exists a sub-clinical, less acute form of moral injury that niggles away at our well-being and sense of self and security. At the very least, the poems in this article communicate systemic ethical failings and attendant torment and grief.

Woodbury concludes his article on climate trauma by summoning T.S. Eliot’s epic ‘Wasteland,’ stating that ‘the melancholic, dying natural world of the fisher king is restored when the knight Perceval asks the mortally wounded king the simple, heartfelt question “What ails thee?”’ (para 51) Woodbury goes on to assert that it is unacknowledged trauma that ails us. While the dots between trauma and public health are now being connected, both in scientific literature and in the public consciousness, there has been little focus to date on how contemporary writing witnesses and testifies to this connection in such a way as to stress a further connection to social injustice. Meanwhile, writers wrangling with trauma now routinely harness the web as a publication platform both through formal online publication and self-publishing on social media platforms. The relative immediacy and circulation of these forms of publication enables writing that testifies to threat, trauma, and social injustice-crisis in the present or near wake of collective experience.

Poetry that testifies to social injustice related crisis and historical trauma has the capacity to help forge alliances, call forth empathic solidarity, and alter individuals’ perceptions and values. Though there is no evidence of a correlation between this writing and policy change – it is doubtful such a correlation could be proved – it nevertheless constitutes an emerging mode of witnessing with enhanced capabilities for affective and moral injury resonance and empathic solidarity.