An Archival-poetics Praxis

The colonial archive is not an easy place to navigate. As Indigenous researchers, we approach these archives tentatively, sometimes with trepidation, and always with caution. Archival-poetics, as a method, emerged as a slow, situated unfolding through the immersion and telling that comes with data collection from multiple sources; an embodied reckoning with the state’s colonial archive and those traumatic, contested and buried episodes of history that inevitably return to haunt. These records highlight policy measures targeting Aboriginal girls for removal into indentured domestic labour and trigger questions about surveillance, representation and agency; they bear witness to the state’s colonising and archivisation processes and reveal what is both present and absent on the record.

My own family research manifested as a feverish gathering and hoarding of primary source materials from state-based collections, tracing paper trails and memory fragments from multiple sources; an overwhelming material accumulation included file-note surveillance data, letters, correspondence files, government inspector reports, museum genealogies, data cards and photos. Like Julie Gough’s (2001: 70) ‘methodology of detection’, I was searching for that underbelly of meaning in historical records to make sense of the seething, colonising backdrop to our lives, ‘like detectives examining the crime scene of our life’. These documents were like mediums through which emotion and ideas are transmitted, and through which the past can speak where other stories might yet be buried (Gough 2007). They revealed critical minor histories which became the source of my creative inspiration, particularly for the women in my family and how they carefully and strategically negotiated gendered and racialised conditions of empire that were designed to control and oppress them.

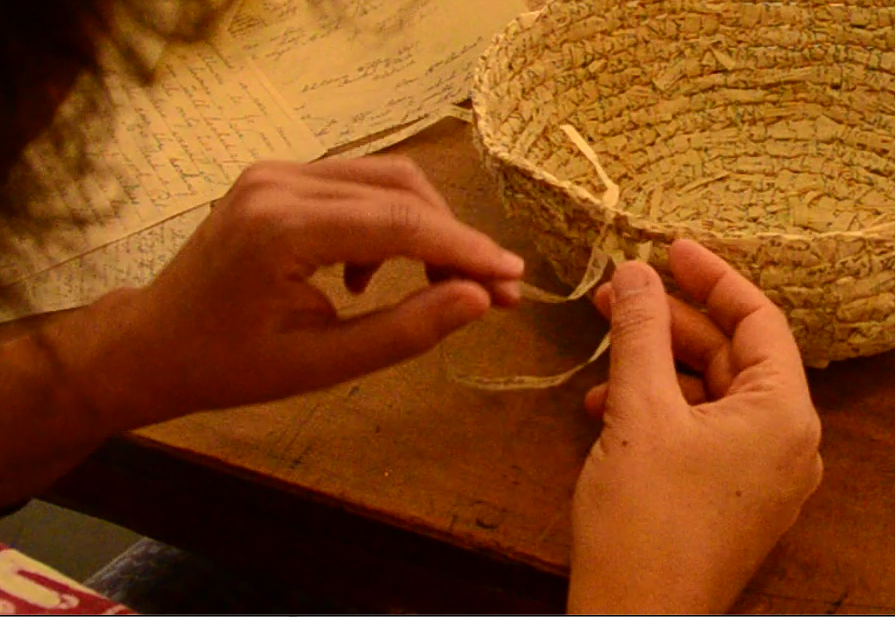

This archive became a conduit for an unconscious assemblage of feelings, lessons and stories with potential to make meaning or sense of our collected and collective lives; a site for hopeful and just futures where liberating ‘acts of remembering and regeneration occur’ (Enwezor 2008: 47). I unwittingly replicated the very thing I was attempting to disrupt, the Archive Box; locked-in and vacuum-sealed with my ancestors, navigating a violent entanglement of myth and truths sustained by imperial fantasies to shape so-called official realities. The only way for me to reckon with it all was to examine the origins of the archive itself, consider new offerings for the future record, write poetry and weave my way out.

This research culminated in a body of poetry and text-based/mixed-media work featuring family archives with intention to reveal their agency and attest to their strength, courage and proactive engagement with the state, and to shine a light on their legacy of intelligence, refusal and activism (Harkin 2019, 2020).

Weaving the archive, video-still, Brad Darkson, 2013.

There is a whole ritual in weaving, and for me it’s a meditation … from where we actually start, the centre part of the piece, you’re creating loops to weave into, then you move into the circle.

–Aunty Ellen Trevorrow in Bell 1998.

The close-knit connection of each row gives the woven object its strength, the connection that family members have for each other is as strong as the woven object.

–NLPA 2011.

When I contemplated weaving with my nanna and great-grandmother’s letters, I lovingly recalled all the lessons in my early twenties by Aunty Ellen Trevorrow and other Ngarrindjeri elders at Camp Coorong, a cultural education centre near the township of Meningie, South East South Australia. The cultural continuance of Ngarrindjeri lakun (weaving), especially in the face of extreme disruption, trauma and government intervention, is testimony to the perseverance, beauty, pride and strength in Ngarrindjeri tradition, and of cultural weavers today. As cultural praxis, weaving is one means to strengthen identity and relationships across generations, invoking personal memory and storytelling, and intimate connections with ancestors (NLPA 2011).

As a signature literary trope (Allen 2002; Momaday 1968; Owens 1998), ‘blood memory’ became central to Archival-poetics as a reclamation response to personal and collective loss; an active remembering, recollection, recuperation and refining relationships to knowledge to strengthen a sense of self, identity and place: ‘blood trails that we follow back toward a sense of where we come from and who we are’ (Owens 1998: 150). It is our corporeal connectedness and belonging through genealogy-narrative across time and place; our ‘relationality’, centred through ways of knowing, being and doing, and grounded in holistic inter-connectedness between and among all living things (Moreton-Robinson 2000, 2017). As a narrative tactic, blood memory is a means to write back to the state’s colonial discourses and fixed imaginings on blood, constructions of race and identity, and the construction of personal story (Allen 2002). It is also a means to re-imagine history and contribute to communal memory through the intergenerational transmission of knowledge pumping through individual and collective bodies and societies.