First pages of Oliver Ortega’s ‘Nasa sa Isip’

In the second part of Desire, he asserts in a prose poem, as a reflection of what is being done in ‘In the Mind’ and to amplify his bias towards what he says is ‘this type of poetry’: ‘It is possible that we are writing now to erase.’ This is what ‘In the Mind’ proves to us. Ortega wrote to erase Marx’s texts. He erased to write his text. He erased to mark the moment. It can also be recalled here what Octavio Paz says in the poem ‘Letter to Leon Felipe’: ‘To write poetry / Is to erase the written.’ Ortega’s declaration that we may be writing today to erase, especially with the emphasis on today, the present, and the contemporary, is rather bold, but it is not without basis. The poetics and politics of erasure continue to proliferate as can be observed, for instance, in the collection of erasure poems at Poets.org. Or in the publication of chapbooks and full-length erasure poetry books in recent years such as Hotel Almight (Sarabande Books, 2020) by Sarah J. Sloat, 20 (Alternating Current, 2020) by Jennifer Roche, Grating, Darling, Full of Dirt (Common Meter Press, 2023) by Erin Dorney, and The Fergusson Report: An Erasure (Knopf, 2023) by Nicole Sealey. After all, poet Will Cordeiro gets it right in his extensive review of the poetry of erasure in Diagram: ‘All writing is erasure’ (Cordeiro).

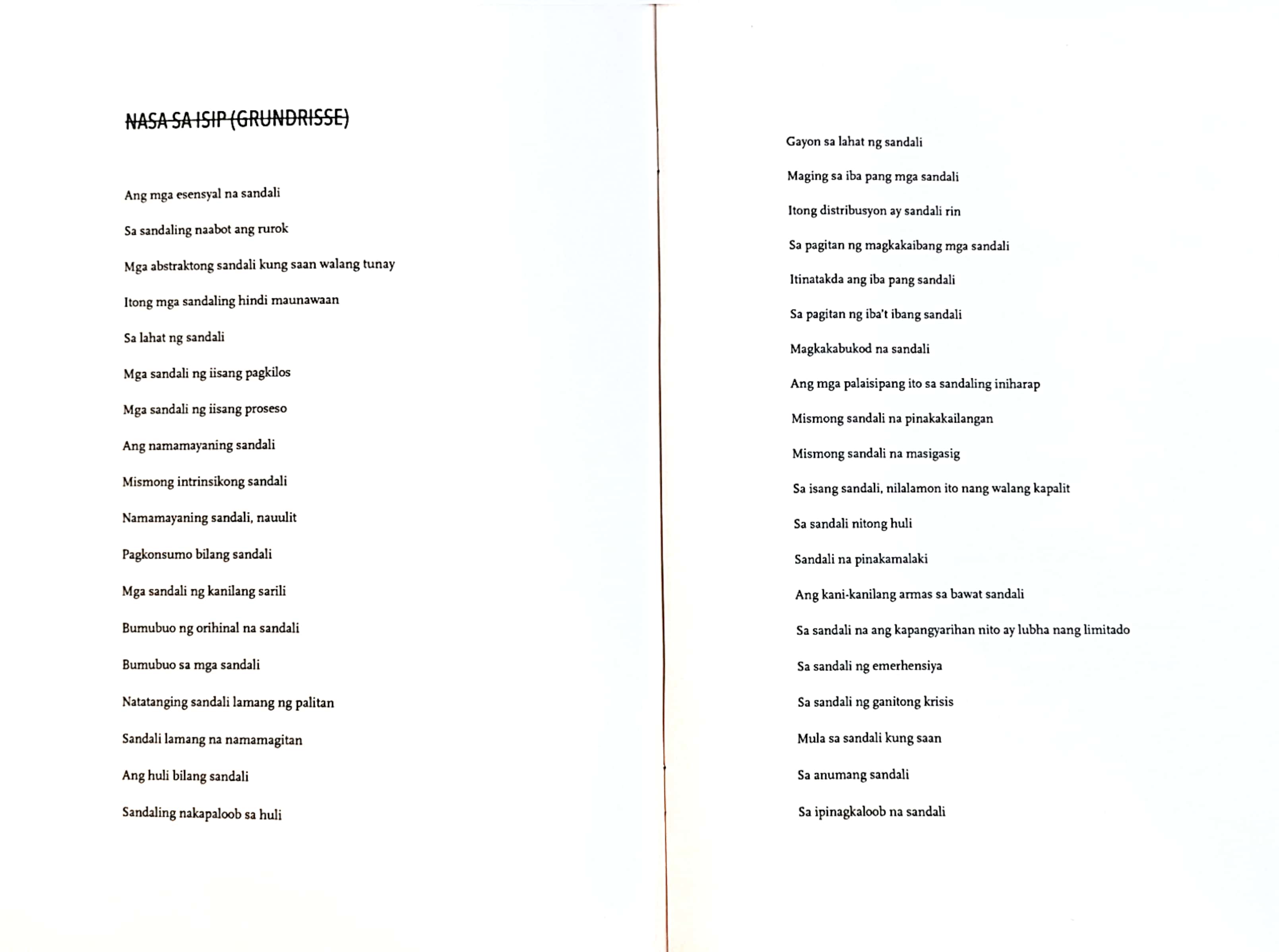

In his marking of the moment, in the process of erasing or capturing the necessary moments in Marx’s texts, Ortega is remarkable for understanding and making us realise that even these moments will not be enough. As with the marking of time in the first two books in the trilogy that posits that while the marking of time remains, time also paradoxically continues to erase these markings, the same is being posited in ‘In the Mind’ – words left out or derived from the source material are inadequate or inaccurate. However, although these words are not accurate, they are still necessary. Hence, this is how Ortega wrote the titles of the two parts of ‘In the Mind’ – with strikethrough: ‘Nasa sa Isip: Grundrisse’ and ‘Nasa sa Isip: Das Kapital.’ Here we can recall – and Ortega certainly evokes – Martin Heidegger’s concept of ‘sous rature’ that Jacques Derrida would later expand on. In Gayatri Spivak’s translation of Of Grammatology, Derrida calls sous rature ‘under erasure’:

This is to write a word, cross it out, and then print both words and deletion. (Since the word is inaccurate, it is deleted. Since it is ne– cessary, it remains legible.) … In examining familiar things we come to such unfamiliar conclusions that our very language is twisted and bent even as it guides us. Writing ‘under erasure’ is the mark of this contortion. (Derrida 14)

By crossing out the titles of the two parts of ‘In the Mind,’ Ortega seems to put not only the titles but the entire texts of the two parts ‘under erasure.’ This means that his derived words from both Das Kapital and Grundrisse will neither be adequate nor accurate. However, these words remain necessary. It can almost be compared to what he did in the line ‘You didn’t say A moment! ’ Cancellation and/or interruption is the mode. Interruption is important to Ortega. That’s why he says there seems to be a long interruption between ‘In the Mind’ and ‘Random Thoughts’ in the form of Engels’s essay. To this, his statement in an essay about the project can be added: ‘In my poetry, interruption is an important factor to have the opportunity to look back and know how to continue more effectively’ (Ortega). Again, Ortega’s exceptional awareness of his project and the methods he uses is evident here. It is apparent that this interruption he mentions is the reason why it took so long to complete the books he started in 2007. It seems to be included in his marking of the moment as he says:

I want to feel the transformation of the poem throughout the time that I devote to it – the possibility of changes in the project itself. I also want to feel how I am being changed – my consciousness, convictions and beliefs; the location of oneself at a particular time and place – over time. (Ortega)

And adds:

Desire, as the third volume in the planned series of books, is devoted to the future. However, according to Chris Nealon: ‘Maybe it’s wrong to think of somedays. Maybe meanwhiles? I like that better because it’s the best way to think about the relationship between poetry and history.’

I like this sense of the meanwhile, of the moment, because it explains the changing trajectory of Desire. Meanwhile, here are the prose poems. Meanwhile, this is what I did with Engels’s work.

The future is created from today’s small moments. (Ortega)

From the last quote, we can understand why Ortega values the moments – which he marks – because they need to be marked even if they are not enough – because this is where the future is created. It can be assumed then that his ongoing expansion and extension of the scope of time in the development of his project and without necessarily eyeing completion, is – as he says in another poem in ‘Random Thoughts’ – the ‘repository of possibility [that] are vital options for action toward the future.’