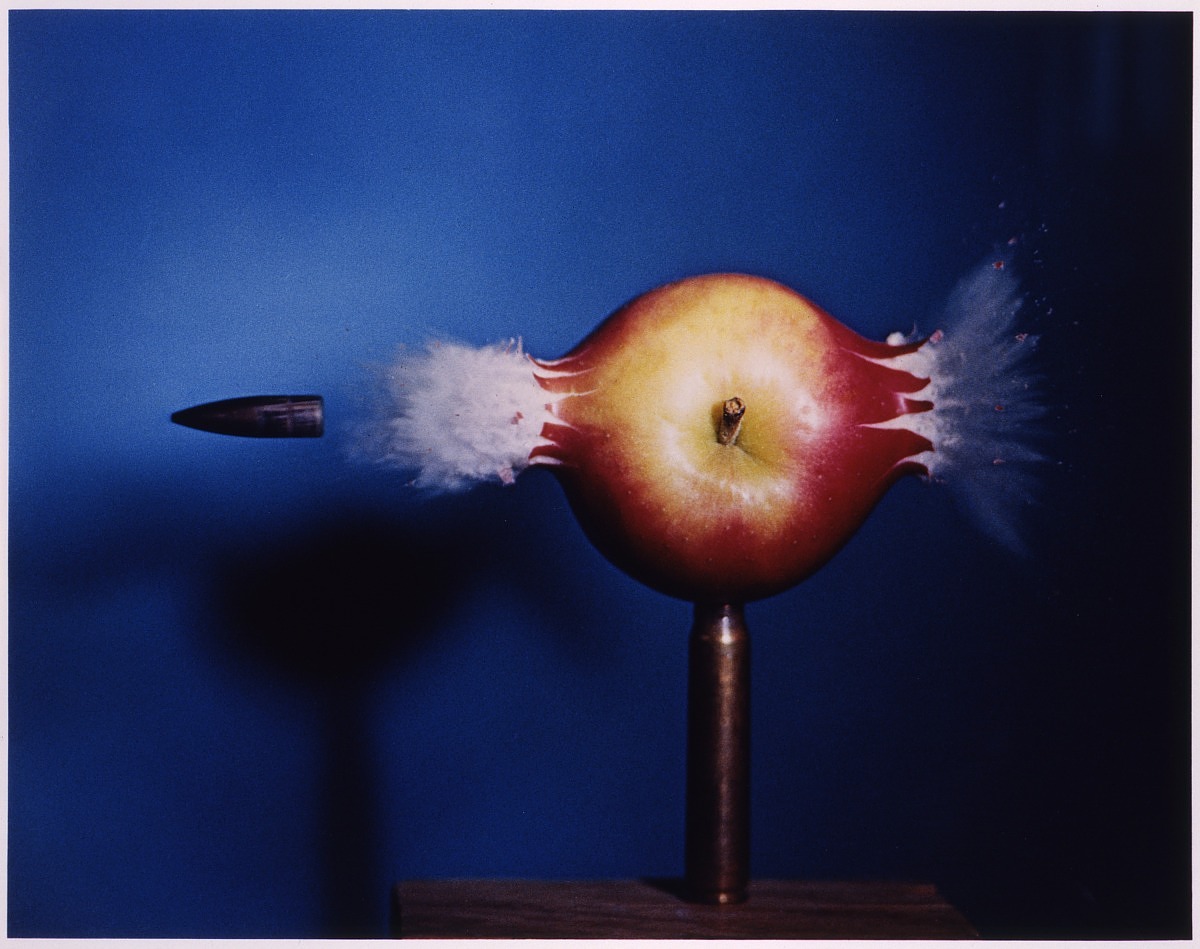

Harold E. Edgerton, Bullet through Apple, 1964, printed 1984, dye transfer print, sheet: 16 x 20 in. (40.7 x 50.8 cm.), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Richard F. Young, 1991.89.14

This desire to pause time would be expressed in another epigraph, also from Saint Augustine, in A Few Moments, Merely: ‘The present hath no space.’ Although this ‘present’ of Saint Augustine cannot be directly equated with ‘a few moments’ of Ortega which seems to refer more to ‘time passing,’ this ‘present’ can still be considered as the desired moment in A Few Moments, Merely, especially if we look at the longer passage from Saint Augustine’s Confessions where the epigraph came from:

One hour is itself constituted of fugitive moments. Whatever part of it has flown away is past. What remains to it is future. If we can think of some bit of time which cannot be divided into even the smallest instantaneous moments, that alone is what we can call ‘present.’ And this time flies so quickly from future into past that it is an interval with no duration. If it has duration, it is divisible into past and future. But the present occupies no space. (233) [Emphasis mine]

Isn’t ‘some bit of time’ equivalent to ‘a few moments, merely’? In Saint Augustine’s thesis, this ‘some bit of time’ or ‘present’ is a threefold present. He said, ‘It might be correct to say that there are three times, a present of past things, a present of present things, and a present of future things.’ He added that ‘the present of past things is the memory; the present of present things is direct perception; and the present of future things is expectation’ (437). If we follow Augustine’s line of thinking, as Ortega did, then the ‘memory’ in the ‘memory of beauty,’ by substitution, is the ‘present’ or the ‘moments’ of beauty that Ortega tries to keep a record of.

The two books, therefore, are indeed closely related or complementary. The statement in the first section of A Few Minutes, Merely that says

The past cannot be revisited. Except for a note or photograph

is also in anticipation of its subsequent book, Notes on the Memory of Beauty. Only at the moment of the publication of this book would we be aware, in retrospect, of the anticipation that happened here because we do have proof of said anticipation – the actual book A Few Moments, Merely that contains, along with Ortega’s other works, the poem ‘A Few Moments, Merely’ which is the source of the aforementioned excerpt. The attempt to freeze or frame the moment can also be traced in the poems. In the third poem in Notes on the Memory of Beauty, for example, it says:

At aporia ang simula ng usapan. (And aporia is the beginning of conversation.)

An aporia is a philosophical puzzle. Rhetorically, it is an expression of doubt or confusion as to how to begin. Loaded with these meanings of aporia, Ortega’s remarkably simple lines simultaneously create a huge puzzle and the answer to that puzzle. How can a skeptic get to start? When, if you continue to doubt you will not be able to start? But this sheer hesitation to begin is actually the ‘beginning’ according to Ortega – a great paradox, then. Notice that the beginning of Ortega’s line begins with the conjunction and – ‘And aporia is the beginning’ – which implies then that this beginning line is also merely a continuation of other previous lines or thoughts/concepts and is not the very beginning. Although it declares itself to be the ‘beginning’ – ‘aporia is the beginning’ – it simultaneously dismantles its statement, its structure, and creates, in deconstruction, a final impasse. In creating this final impasse, the moment seems to be halted, and the thought/concept is framed to be revisited again and again – to begin again and again. Although Ortega says that ‘aporia is the beginning,’ what Samuel Beckett says at the beginning of his novel The Unnamable (1959) seems to be heard in what he (Ortega) doesn’t say: ‘I should mention before going any further, any further on, that I say aporia without knowing what it means’ (291). The same expression of aporia and enactment on the page of seemingly philosophical puzzles in Ortega’s poetry can also be observed in A Few Moments, Merely. See part three of its title poem:

Sabi nila, ang isa sa pinaka- malaking problema (That they say one of the big- gest problems) ang kung paano sasabihin ang problema. (is how to say the problem.) Kaya nagsimula tayong maghiwa ng mansanas (So we begin to slice apples) kaysa mag-usap. (rather than talk.)

With great directness and precise shortness, the verses come to us like a transcription of a message using Morse code. Each line registers and takes on its own weight or meaning (although it is only a fragment or phrase) as it moves towards the construction of the narrative or sentence. When the meaning of the sentence is formed, we can sense an undisclosed ‘problem’ between the speaker and his interlocutor (referred to as the collective ‘we’) so what they start to do is ‘slice / apples’ instead of talking. However, it is reasonable that this ‘slicing of apples’ is the ‘start of the conversation’ – the metaphor of aporia for Ortega. Further, these lines – from ‘[t]hat they say’ to ‘rather than talk’ – can also be read as the substitute for ‘slicing of apples.’ In short, these written words were lined on the page as a metaphor for one of the ideas contained in these words – the metaphor of ‘slicing of apples’ as a ‘conversation starter.’ Therefore, the poem – or in particular, this part of A Few Moments, Merely – is at its core an enactment of what it expresses and not an instrument that ‘transmits messages/meanings.’ The ‘enactment’ of the poem of what it ‘says’ freezes/frames the moment of the event/concept being unfolded in the poem. Freezing/framing of the moment that does not keep the moment still or static but paradoxically also keeps it in motion (‘as starlight traveling in the darkness of space’). It can be said that this is the moment equivalent to ‘time passing’ or the ‘present’ without duration and the only part of time that, for Saint Augustine, can be measured. For his thesis of the threefold present, this is the ‘present of things present’ that we give attention to or have immediate awareness for. This same attention to the significance of the moment is what Ortega’s works demand of us. Though these are merely a few moments, they have a narrative and complexity that is layered, as evident in the poems ‘Sandali ng Dalaw (Moment of Visit),’ ‘Sandali ng Katahimikan (Moment of Silence),’ ‘Sandali ng Sulyap (Moment of Glance),’ ‘Sandali ng Katotohanan (Moment of Truth),’ and ‘Sandali ng Mangha (Moment of Wonder).’ In ‘Moment of Silence,’ Ortega says:

Mabilis na lumisan ang dumating. Ni hindi mo naiabot ang iyong palad para makipag-kamay. Hindi mo nasabing Sandali! gayong palagi, ikaw at ang salita ay iisa. (Those who came left quickly. You didn't even reach out your palm to shake hands. You didn't say A moment! though as always, you and the words are one.)