The last time I saw Kathy Acker was in London, in July 1997. I wasn’t sure how she felt about me at that point. I had failed to drop everything to be with her in San Francisco the year before, and I had failed to make a job materialise that would have brought her to Sydney, as she wanted. Things had, I felt, ended in a disappointing but amicable dead end. ‘Just be my friend,’ Kathy said, early on, and I had promised I would.

Being friends is more of an undertaking than being lovers.

Charles Shaar Murray: ‘I met Kathy Acker at a dinner party in a Mexican restaurant in Soho. A little over 24 hours after that meeting, we discovered ourselves to be in love and resolved to spend the rest of our lives together. We spent most of the next five days almost continually in each others’ company.’1

She had decamped from San Francisco back to London, with all its difficult memories, to be with him. She knew she had cancer, or maybe knowing and not knowing. She was already planning to return to San Francisco. I happened to be coming to London on some arts organisation’s tab, so we agreed to meet there, in a city where both of us were strangers.

It seems likely we had a meal somewhere, but I remember nothing about that. The part I remember starts with going to see a performance. What I remember is that it was a one-man show about a gay man living with AIDS who expected to die soon. The performer had such presence, not just with his language and gesture and stories, but with his body.

The performance was in a lecture theater at a London teaching hospital. His only prop and light source was an overhead projector, of which he made brilliant use. The show was both cutting and moving at the same time, a portrait of the state, medicine and technology as much as of this man’s life.

That was the first part of the show. The second was very short. He told us that the lecture room in which he was performing was next door to a former viewing room. In the past, hospitals set aside such rooms for relatives to view the recently deceased. In a viewing room they could be arranged properly as a kind of tableaux for relatives to pay their last respects. The performer asked us to wait five minutes. Then we were ushered into this viewing room.

The viewing room would have held maybe a dozen beds, a sort of ward for the dead. There was only one bed in it, and that bed was the only thing lit, the room being otherwise dark. The colors I remember are sienna, mahogany and salamander. Or maybe those are feelings. In the bed was the performer, neatly arrayed, completely still. He was acting as his own corpse. This was the second part of the show.

Part of the point this made was that even in the late nineties, a gay man with AIDS could not count on his real friends, his family of choice, being able to be with him in hospital, or to have the right to see him in death. There was something dignified about the viewing room, the intentional staging of the dead one, and the performer turned this to his advantage. We strangers were in a place to see his future self where his friends might not.

In the viewing room, everyone was silent. The energetic buzz of premature after-show conversation dropped down to nothing. We all just stood around. Kathy was next to me. I wanted to hold her hand, or something, but I did not know if she would want me to, or if it would make her feel worse. We just stood in the audience, this audition for silence, being silent together. It was such a naked contrast to the animated quality of the first part of the show. Then we left.

Memory is a genre of fiction. For a long time, I have wanted to know what the performance was that Kathy and I saw on our last night together. I found out finally by asking on FaceBook and tagging some people, who didn’t know, but knew people, who knew people, who knew: The Seven Sacraments of Nicholas Poussin, by Neil Bartlett.

I ordered it from Amazon. Read it. Now I know it was performed at Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel, from the first to the seventh of July. I had forgotten that most of it was about Poussin’s paintings of the sacraments. Memory changed the ending. There is indeed a second half of the performance, but Bartlett sits in a chair opposite an empty bed, as if he were holding the hand of its occupant. The pillow is creased in the middle as if a head lay on it.

Neil Bartlett: ‘You will have noticed, those of you who were brought up with these words as I was, that I keep on remembering them wrong. I have erred, and said things, like I’ve lost my place. I have left out the words which I ought to have said, and I’ve put in some of those that I ought not to have put in, and I just can’t help it.’2

Kathy didn’t want to go out, so we took the tube to her place, getting off at Angel station. Her apartment lay alongside one of London’s canals. I could see canal boats tied up there. Kathy often said she wanted to be a sailor, to take off into the rolling waves. She was a sailor in the ways that were available to her. Writing (fucking) was her sea. I imagined her pottering about on canal boats, where the city meets the rising tide.

Her address was 14 Duncan Terrace. I’m looking at it again on Google Maps. The red door is as I remember. I see that when Street View last cruised this block, it was for sale. On the other side of her street is not the canal, it’s a strip of green parkway. There’s waterways nearby, and if I zoom in on the satellite image I can see narrow-boats pulled up along the banks. Looking at the satellite images, and playing with the street view, triggers other memories, whether real ones or not I don’t know.

I remember her flat as one of a row of identical brick Georgian terrace houses. Judging by the quality of motor parked there, quite a posh area now. The brick grimy, the white-painted details shiny in moonlight. The famous writer Douglas Adams lived on the same block, Kathy said. He could afford a whole townhouse. His lights were on. I caught a glimpse through the window of his bookshelves, in white wood.

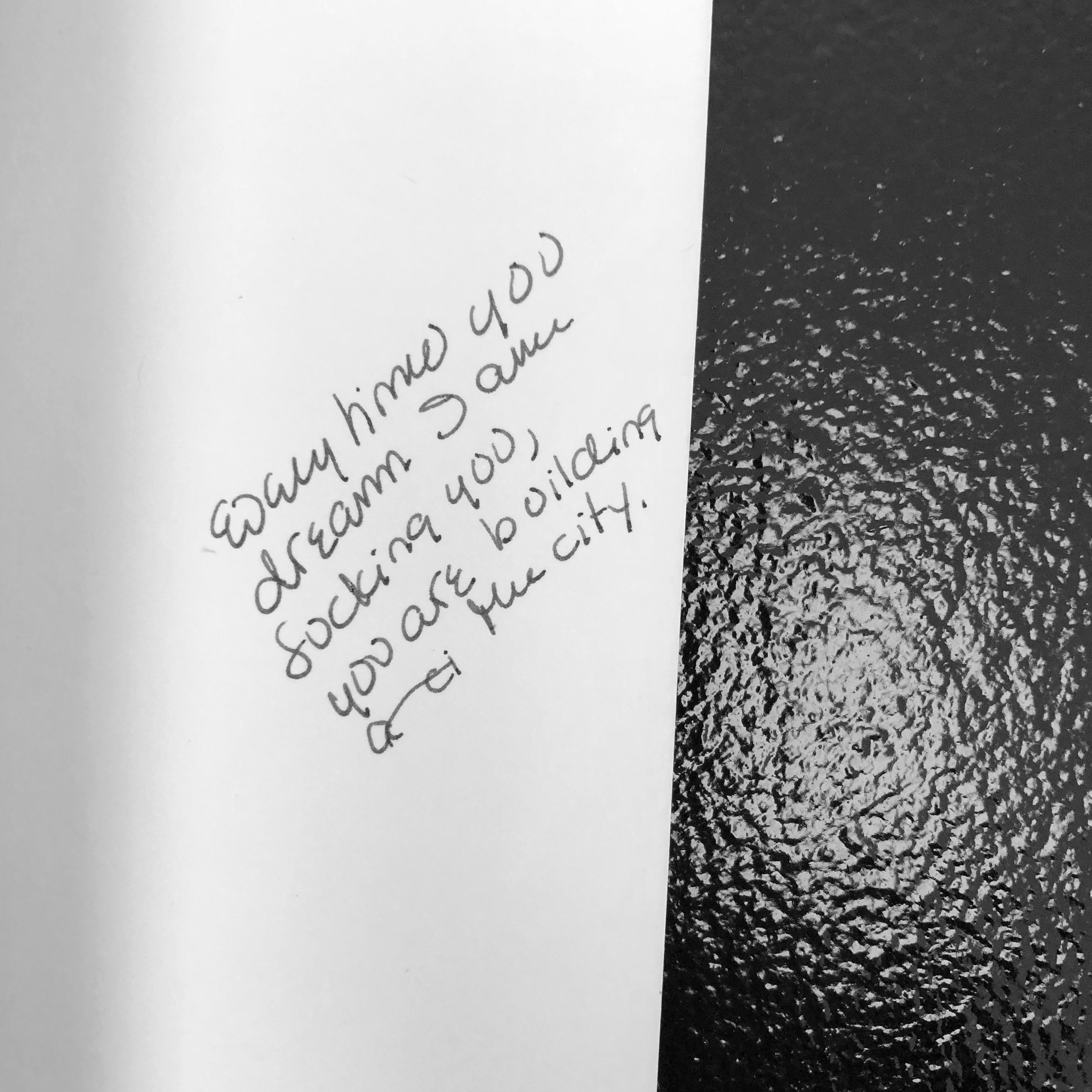

In memory Kathy’s place seems like a basement flat but I don’t know if that is a memory of architecture or of mood. Kathy rummaged around in the kitchen for wine, glasses and an opener. I looked at the bookshelves. All her books seemed to be here, neatly arrayed in alphabetical order, in double rows, just like they had been in San Francisco. I got a little distracted looking at treasure I would like to read, like I did when I stayed with her in San Francisco that short while. When she was out at the gym I just rifled her books, stealing lines into my notebook. I was always careful to put them back in the right place.