Balloon’s earned his name. He’s a six-foot-two barrel of a man with a voice that booms. He’s a giant among Koreans. A gentle giant with a wide, open face. The day is hot. His brow drips when he gets excited. Bo Yeon brings him a tissue. Bo Yeon brings water and coffee. She brings a bandaid. She watches everything with a hopeful half-smile on her full moon-face. Hyung Seok sits between them. He has a long expressive face landscaped by a strata of old scars. His hands are delicate and when he talks his fingers make tiny sculptures in the air.

Balloon’s earned his name. He’s a six-foot-two barrel of a man with a voice that booms. He’s a giant among Koreans. A gentle giant with a wide, open face. The day is hot. His brow drips when he gets excited. Bo Yeon brings him a tissue. Bo Yeon brings water and coffee. She brings a bandaid. She watches everything with a hopeful half-smile on her full moon-face. Hyung Seok sits between them. He has a long expressive face landscaped by a strata of old scars. His hands are delicate and when he talks his fingers make tiny sculptures in the air.

Balloon’s a graphic designer, Bo Yeon an arts organiser and Hyung Seok an architect. They’re from the SAII Moonji Cultural Insitute. We’ve been emailing for months about collaborating. Now we’re sitting together in their chic Seoul offices. Around the table are Australian poets Terry Jaensch, Ivy Alvarez, Barry Hill and David Prater. It’s like a nervous first date. Balloon mops his brow. He’s getting excited again. So are we.

We’d come to Korea for a very official tour, to participate in the Third International Seoul Forum for Literature. The poets were presenting alongside the officially recognised names in Korean and world literature. The format was official too: four and a half hour sessions, held on the top floor of a skyscraper with an artificial forest in the lobby.

As a contrast to the Forum, we’d asked SAII to give us an unofficial tour, to show us the unseen side of the city. SAII sit at the intersection between writing, the humanities and media art, and have a critical, experimental flavour to their work. With huge generosity, they’d taken our suggestion of a city research tour and run with it. We would spend three days exploring the city, writing and discussing, then collaborate on some kind of a creative work.

Balloon tells us they will show us the guts of Seoul city: hidden and strange places, the machinery that makes the city work but never sees the light of day. Hyung Suk says they’ll show us the layers of history that still exist amongst and beneath the new city. A different kind of culture, one that isn’t on the timeline or simply driven by aspiration.

Like the Mongolian gangster slums, chimes an excited Balloon. We thought we’d take you there at night. There’s been a lot of fighting between gangs.

He sees our faces.

Don’t worry, it’ll be safe. I look Mongolian!

TOUR ONE: SEX, DEATH AND REBIRTH

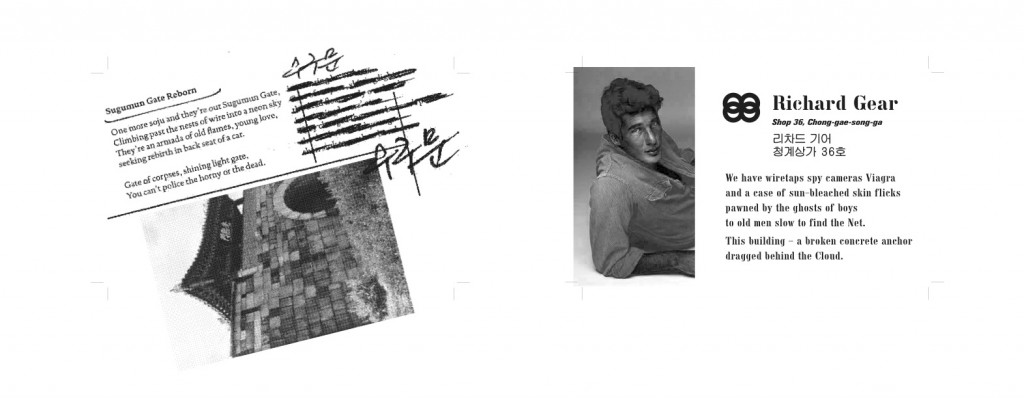

The old city wall cuts through modern Seoul. Its medieval spine dives down beneath the built-up lowlands, then resurfaces to climb the bush-covered mountains that dot the city. Four enormous city gates stand at the cardinal points. In between are smaller unofficial entrances. Our tour begins with one of these. It’s called Sugumun. The plaque translates this as ‘Gate of Shining Light’. It really means ‘Gate of Corpses’. This is where the dead were carried from the city to be buried outside the walls.

For Hyung Seok, it seems this compact area encompasses the full spectrum of birth and death in Seoul. The dead were carried from the city at midnight. Their ghosts were said to float above the walls. On dusk, we walk up a gentle rise beyond the gate, and an armada of paper lanterns floats overhead, buoyed aloft by gently flickering candles. Against the high-rise skyline they look like the floating souls of another age. It feels magical. Bo Yeon looks delighted, and I wonder if our new friends have somehow arranged this beautiful, illegal display.

These days, after midnight, the road beside the wall is a notorious lovers lane. Teenagers park up and make out. I imagine the ghosts of the old dead entering the white curved wombs of these cars, looking for rebirth. And just beyond the lovers lane, Hyung Seok points out another womb, a curvilinear maternity hospital. Many of the area’s children were born there. This was one of the first buildings of its kind in Seoul, the birthplace of Modernity in Korean architecture.

These days, after midnight, the road beside the wall is a notorious lovers lane. Teenagers park up and make out. I imagine the ghosts of the old dead entering the white curved wombs of these cars, looking for rebirth. And just beyond the lovers lane, Hyung Seok points out another womb, a curvilinear maternity hospital. Many of the area’s children were born there. This was one of the first buildings of its kind in Seoul, the birthplace of Modernity in Korean architecture.

Following birth comes education, and adjacent to the hospital is Hyung Seok’s old high school. In between and instead of his formal education, he and his friends explored nearby alleyways. He takes us into a maze of curved streets that are home to migrant worker populations, mostly Mongolian, many illegal. We are told these populations have been a hidden engine in Korea’s rapid economic growth. The proportions of many buildings are medieval, with low doorways and ornate tiled roofs. The sound of steam presses and sewing machines leaks into the evening air. It is still early, and the area feels quiet. There is no sense of the violence Balloon talked about.

We turn down an especially narrow laneway. Every few metres a doorway opens onto stairs that vanish into the dark.

What’s up there? asks Ivy.

Hyung Seok laughs, a little sheepish.

Beer, he says. Twenty beers equals one woman.

Bo Yeon whacks him on the arm.

How do you know that?!

Our friends are indicating the brothels in this district, and the fact that sex is so close to death and birth. But we are still too shy of each other to talk about the sex trade’s oblique economy and its relationship to mainstream Korean culture. No-one suggests climbing those stairs. We joke instead about the method of payment acting as a prophylactic. We leave this narrow, close-walled section of Seoul’s red light district and emerge suddenly into roaring traffic. We’re close to Dongdaemun History and Culture Park. I’m struck by the proximity of these worlds.

Our friends are indicating the brothels in this district, and the fact that sex is so close to death and birth. But we are still too shy of each other to talk about the sex trade’s oblique economy and its relationship to mainstream Korean culture. No-one suggests climbing those stairs. We joke instead about the method of payment acting as a prophylactic. We leave this narrow, close-walled section of Seoul’s red light district and emerge suddenly into roaring traffic. We’re close to Dongdaemun History and Culture Park. I’m struck by the proximity of these worlds.

There is a strand of psychogeography that posits walking and listening as the key to understanding a city, by slowly becoming attuned to the mood and vibration of place. We are doing something slightly different. We walk in a self-contained group, as intent upon each other as the city. We lean close to catch the words of our hosts, finding common language, and its limits. Like a first date, it’s tiring, but exhilarating.

TOUR TWO: CONCRETE ANCHOR

Before Terry arrived, he Googled ‘Gay Poet Korea.’ The name Gyi Hyung Do came up, telling the story of a much loved writer who died young. The official version of his death makes no mention of his sexuality, and suggests he died in a ‘movie theatre’. Homosexuality is a taboo topic in Korea, but there are rumours that Gyi was gay, and that it was a men’s club where he died. When we meet for tour two, we find the innocuous ‘movie theatre’ where some say Gyi Hung Do died is nearby. We take a quick detour.

The cinema is in another forgotten Modernist building, reached via a rooftop courtyard. Inside, the most recent film on offer seems to be Gone with the Wind. Elderly couples in pastel tracksuits chat while waiting for their films to start. It feels as if they’ve been in the same chairs, laughing and growing old among the dusty pot plants, since 1962. It is strange that Gyi’s official death has been located here, as if someone chose the most nostalgic, heterosexual place they could think of to contain the rumour of Gi’s homosexuality.

We leave the cinema and walk, following a stream running east-west through the city. Hyung Seok tells us there was once a natural stream running along this path. As the city developed it was built over, but in recent years a man-made stream has been carved through the urban landscape in its place. The new waterway runs within a tree-lined concrete channel and is powered by pumps, as if on life support.

Our main destination is a beautiful and strange crumbling industrial precinct called Chong Gae Sang Ga. This was the location for parts of Park Chan-Wook’s 2003 film Old Boy.

At its heart is a narrow two-storeyed building of raw concrete running north-south for about a kilometre. It was a bold statement in its day, reaching north towards the border in a gesture of architectural reconciliation. Today, the building has been cut in half by the man-made stream. The two bisecting lines form a huge cross. Atop a bridge at the centre of this cross sits a large steel sculpture. It looks like a giant acupuncture needle, pushed deep into the skin of the city. A Christian group has gathered at its base to sing in the morning sun.

Our first indication of the area’s current usage is a sign that reads ‘Xanax Viagra Spy Cams DVDs’. The great open upstairs courtyard is filled with displays of dust-furred 5¼ ” disk drives, dialup modems and antique surveillance cameras. There are sun-bleached skin-flicks on DVD and video cassette. The stalls are closed today and the place feels forgotten, but during the week there is a healthy trade. This work of utopian Modernist architecture has become a kind of offline, hard-copy version of the seedier side of the internet. If the modern internet is ‘The Cloud’, this is the broken concrete anchor dragging along behind.

After each tour we relax together, sharing food and beer among the roar of Hongdae, learning more about how culture is made in each country, and discussing what form our collaboration could take. Terry hits on the brilliant idea of business cards. They are ubiquitous in Korea, the first thing you exchange when meeting someone. They will make an ideal medium for delivering poems. In the way a villanelle or haiku imposes structure, so does a business card: concise, both visual and textual, easily given and easily received. We resolve to each write two or three short poems, and Balloon and his partner Jin Kyung, both graphic designers, will work them up into finished designs. It will be a huge amount of work for them, particularly Balloon who will do the overall layout. In typically generous fashion, they’re up for the challenge.

TOUR THREE: AGE-OLD OLD-AGE SHAMANISM

On an earlier walk, Balloon pointed out a house flying two flags: red for this world, white for the next. The flags mark the house of a traditional shaman. These houses are dotted everywhere amongst the high-rise city, and doing a roaring trade.

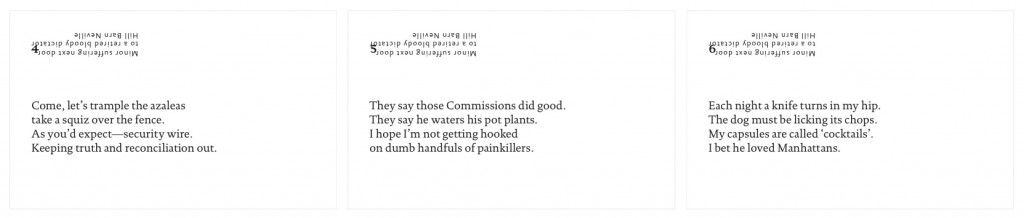

On the morning we’re due to visit and have our fortunes told, Barry has severe back pain. I stay behind with him. We will spend the day at Yeonhui Writers Village. Laid up in bed, Barry has time to contemplate the fact that former Korean dictator Jun Do Hwan lives over the back fence.

The others leave for the day, laughing and joking about what the shaman will tell them. They are joined by Seoul-based Australian poet and academic Dan Disney. No-one takes the idea of having their fortune told seriously. But when they return that evening, the mood has shifted.

What started as a joke has drawn out all kinds of unsettling questions. The shaman knows things about Ivy that are definitely not on Google. Balloon is told he met his true love a decade ago, and this makes him and his wonderful new partner a little uneasy. Predictions are made about long-lost family members, return invitations to Korea that have already come true, and strange sexual encounters our friends are too embarrassed to translate. Although we are sceptical, and the fortunes come from deep within another language and culture, the common fault-lines of family, relationships and futures quickly emerge.

Korean culture venerates age and seniority. Traditionally, when eating and drinking in a formal setting, it is the oldest who pours the drinks, while the recipient holds their cup with both hands and averts his or her face. The elder also gets the bill. Despite this formal veneration, central Seoul feels like a young person’s city. Following the shaman visit, Balloon, Hyung Seok and Bo Yeon take the others to some haunts of older Koreans.

Korean culture venerates age and seniority. Traditionally, when eating and drinking in a formal setting, it is the oldest who pours the drinks, while the recipient holds their cup with both hands and averts his or her face. The elder also gets the bill. Despite this formal veneration, central Seoul feels like a young person’s city. Following the shaman visit, Balloon, Hyung Seok and Bo Yeon take the others to some haunts of older Koreans.

First is Tapgol Park. Hundreds of old men sit on plastic stools facing a stage. They are immaculately turned out in loose-fitting jackets, baggy suit pants and fedoras and caps. It is a political meeting. But it is not a contemporary political meeting. These men are still debating the politics and ideologies of their youth. The park is divided into factions that go all the way back to the 50s. The world may have moved on but hostility here is still fierce. Not long ago, an argument between two pensioners reportedly ended with a stabbing. This fierceness extends to outsiders. Attempts to take photographs are met with hostile stares.

Plenty of older Koreans prefer dancing to debating. After the park is a colatec, a disco exclusively patronised by the elderly. The music, décor and costumes are suspended in time. Couples shuffle round the floor to the tunes of their youth. Single men, well into their eighties, ask old ladies to dance. A mirror ball ringed with pink neon rotates overhead like a small planet. Where there was once a dance band, a lone young woman sits dwarfed at a bank of eight keyboards. Again, the reaction understandably stony. The impression is that elderly Koreans live separate, sealed-off lives, while the rest of the country moves forward with an incredible outward velocity. It is not clear whether the elderly are being left out, or left alone.

With the tours finished, we find time to write between the last official presentations and dinners. We hand over our work to Balloon and Jin, then they vanish for a 48-hour design bender. They still find the energy to bring drafts for discussion, and when the day of our farewell concert arrives, Balloon delivers a huge box of crisply printed cards. The designs are beautiful. Jin has even hand-illustrated one of Terry’s poems. Balloon and Jin are both gracious and exhausted, and I can’t help feeling that we have asked a lot of our hosts.

That night the amphitheatre at Yeonhui Writers Village fills with a younger crowd. Hyung Seok projects images of rain onto hundreds of white umbrellas hung from the elegant stone pines. Legendary Korean rappers Garion interpret Korean poetry over hiphop beats, while a younger MC with a hybrid Korean-Brooklyn accent interprets Australian poems about cities. Venerable poet Hwang Tong Kyu then stands to read his work in his own voice. He commends the rappers for their experiment, but tells them off for their lack of emotional range. It’s a beautiful moment: a famous poet, well into his seventies, offering lyrical advice to two of Korea’s best-loved rappers.

Later, we show Ivy’s photos of Seoul, and present our collaboration. We take the audience through each card and the story behind it. It is strange but fascinating to offer our Australian-inflected version of Seoul back to the city’s own inhabitants. Everything is bilingual, with different sections of the crowd murmuring and laughing depending on the language. It is hard to communicate the full richness of our experience, and how grateful we are to our hosts, but we try.

The night finishes with a shared meal. A dozen motor scooters arrive bearing a hundred portions of jajangmyeon. We sprawl across the amphitheatre steps and share the warm, slippery noodles with our Korean friends and the delighted audience. We hand out our cards and many try to collect the whole set. The following day we will go our separate ways. We chat about hosting Hyung Seok, Balloon, Jin and Bo Yeon for a similar project in Melbourne. We are spent but happy.

Some of Balloon’s friends were worried we wouldn’t like Korea after the tour and collaboration. The opposite was true. There is something powerful about coming to a country from underneath. It extends our common ground beyond the exchange of official ideas. Older, stranger histories paint a rich picture of the society that produced them. How we respond to this picture reveals much about ourselves.

Pingback: NicLow | Octopuses, oilslicks and earthquakes

Pingback: Human Acts: Han Kang receives the Nobel Prize in Literature – Davey Dreamnation