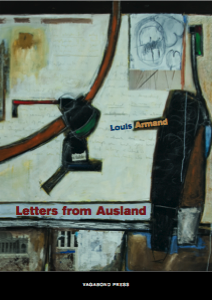

Letters from Ausland by Louis Armand

Letters from Ausland by Louis Armand

Vagabond Press, 2011

To say Louis Armand is a thoughtful poet is both obvious and an understatement. His reach extends beyond the expression of an idea to capture the sensation of the thought itself. He gives thought its heft, urgency and gravity and thus separates himself from being a mere poet of ideas. In his latest collection, Letters from Ausland, he finds that elusive ground between intellect and artistry.

Much of Armand’s poetics is achieved through a sustained hesitancy. The ideas don’t sit complete and static on the page. They circle, pace and weave without ever pinning a subject down. The approach allows the reader to enter, for want of a better word, a mental space where the tone of the piece is as much a part of the idea if not the idea itself. In the opening poem, ‘Something Like the Weather’, he writes, “Nobody needs poetry for this. Or do they?” which in a way sets the tone for the collection. Making a declaration which is immediately undercut by a question brings the topic sharply out of focus. Grand statements are easy to make; more difficult is getting us to reflect on making those statements.

Using questions is one means of heightening the tentativeness, and questions appear in many poems. ‘Paysage Moralisé, Lavender Bay’ finishes with, “Yet why must it seem / necessary, to make the assumption, or pass the judgement?” As a question, the wording is powerful. Can we live without them? I don’t think Armand has the answers or even expects us to find them. Rather, posing the question is part of the overall enticement to think, to suspend our preconceptions, of which assumptions and judgements are important.

In ‘Boy with the Red Piano,’ the question reinforces the overall elusiveness of the opening lines:

Morning birds on telephone wires talking in secret

brain language. Another 4th of May. Grew old and then.

Last night, listening at words for intimation of.

(The avid crowd. The child-teacher, sunkeneyed,

making the obvious into riddles.) But now

isn’t what it was. A green bottle with a contrary

message, washed up from destinations beyond

the vanishing point. Subtract one and add

two more. “Do we own our guilt?”

The clauses present the scene in fragments without securing them. They float freely. You can almost hear them surfacing for a moment before breaking off. When the poem is resolved syntactically, i.e. when something definite is stated, it is a contrary message and that message appears to be a question. The question could be defiant. It could be flippant, and Armand never states clearly what we should be guilty of. Nor should he. This question, like the other two quoted above, is not interrogative. It is not demanding answers. It is only to be asked.

While the tone of the poems suggest something ineffable, they succeed because they are also very concrete. As the scene above illustrates, Armand fixes the poem in the world while also interacting with the mental, the abstract and the suggested. The secret brain language is an indication of this. ‘Leden’ recalls the historical patchwork of Prague, but uses the city with its “numerology / of tramways, the unspoken language of pavement commerce” to hint at something and bring us not just into the city, but into the moment of contending with it. Armand’s tone is even more hauntingly evident in ‘Maison du Cryptoportique (Carthage)’:

The process is by increments: a doorway, a lost

pair of eyes. Stanza by stanza they appear,

one small room leading to another and to another.

To love a woman or a man voicelessly –

These lines suggest the weight of thought in the way they plod from on part to the next. You get a sense of the slow movement of creation itself unfolding. He brings you into the moment of witnessing and it is this witnessing, this observation which Armand appears to be most cautious about.

Observing or references to looking and eyes recur through the collection. There are “glass eye”, “yellow green eyes” and the “mantis-eyed”. In all of this is a reminder that looking entails an engagement. The eye is far from being the clichéd window to the soul. It can relay as much as it absorbs. In the poem ‘Anniversaire’, a glint is rendered thus: “A glint in that eye. / A source of immunity to grief.” Here the eye is a source rather than the usual receptacle. In ‘Hugh Tolhurst, with Lines from a Poem’, the eye receives the world but not without some damage to itself: “a detail conscientiously ignored until it / punches you in the eye”. The final poem in the collection ends with: “after hundreds of hours / of staring, there’s nothing to look at, nothing to see.”

I cannot say conclusively why Armand is cautioning us about looking. The gaze in any form is one theoretical target. However, the poems are not political – or if they must be political, it is in how they open this mental space. What is more important is how he makes the reader wary. The questions, the sketches, and the wariness of the gaze amount to creating a frame of mind in which we are not forced to engage, in which where we are permitted to step back.

Personally, I find his approach and voice liberating. The poems don’t berate, nor are they constrained by identity or a fidelity to manifestos. They are more expansive in their creativity and read as though they are concerned exactly with that moment. At times the poems border on pessimism because Armand is not offering a way out. However, that the pieces allow the reader to be suspended in the moment of creation and contemplation is the overall achievement of these pieces.

Ultimately, the power of these poems comes from the poems themselves. Whatever I tease out is secondary to the experience of reading them. This point is evident in the brilliant eponymously titled long poem. The piece is a blend of memory, startling images and ruminations held together by this resonating voice:

The forms of this landscape are repeated; forms

that become volatile through too much seeing –

placed as we are on this isthmus of our middle state

between denunciation and indifference. What

is a poet for in a destitute time?

I wouldn’t go so far to say that Armand feels his thoughts, but he does invite us to explore their hidden dimensions.