Floribuna by Judy Morris and Ian Gibbins

DIY, 2015

How far we are from the radical days of realism. Prior to Adorno’s dismantling of Lukacs and the Stalinist led state institutionalisation of it, realism may have laid claim to being an innovative aesthetic with agreeably progressive political inclinations.

One familiar Australian case that demarcates the fault lines of realism was the Katharine Susannah Prichard/Dorothy Hewett argument in the post-war era, an argument that was as political as it was aesthetic. These two actors fought about the merits of the Soviet Union and the benefits of a social realist literary sensibility. Where though are the inheritors of realism in poetry now?

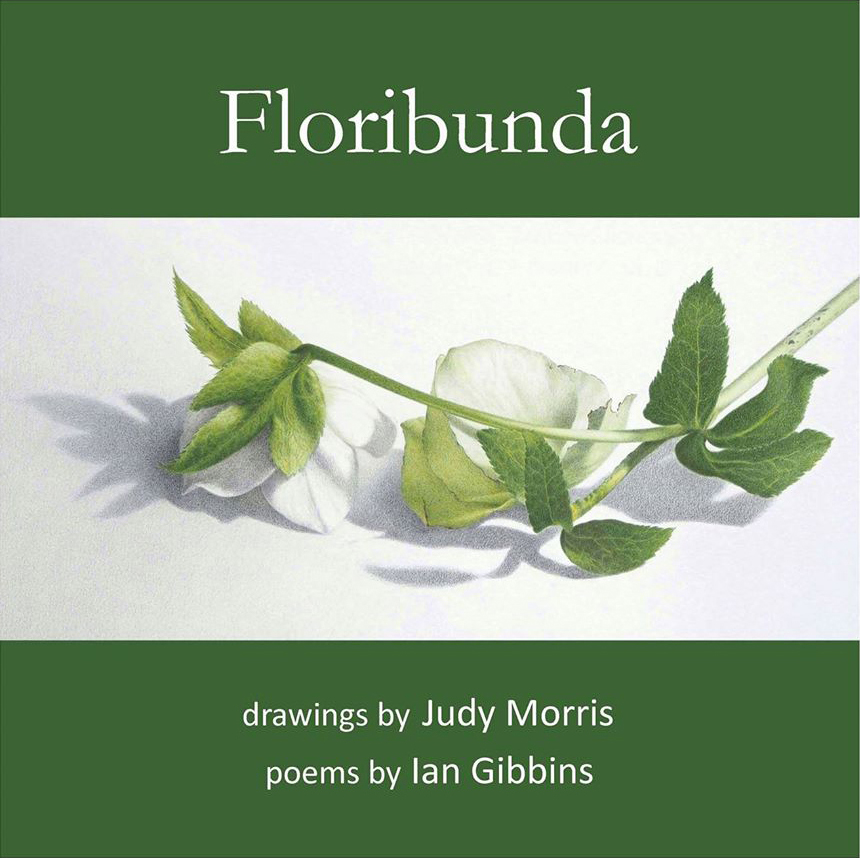

They are potentially everywhere if mainly a little deformed, a little skew, a little tame. Floribunda is one such place to look. It features drawings of the Adelaide Hills’ flowers by Judy Morris and corresponding poems by Ian Gibbins. The realism of the artwork is clearer than that of the poems. Indeed, the drawings aim for a warm yet photographic representation of the real in a way that intends to map the ‘object itself’ as it exists in nature. If some lines are a little indistinct that is only on account of the material (pencil) that rendered it so. In this iteration Morris is not a child of Impressionism, let alone some iteration of Modernism. One need only consider proportion to support this – the stamen, the petals, the bee, the leaves all correlate to some ideal type, some holotype, some specimen out there. This is not a face from Picasso.

The poetry is consistent with that. Gibbins’ work is not necessarily in a realist tradition as Hewett may have marked it out – perhaps Floribunda could not be further from the lives of ordinary people struggling. But in its style and form it picks up on the conservatism that Adorno correctly ascribed to realism. However, Gibbins is not an anti-Romantic, as early realist writers were. If anything, he luxuriates in rich, florid descriptions, embracing a style that is gilded and a little heavy. It borrows then from lyric in an overwrought, quasi-maximalist pursuit of beauty, which is seen in ‘Knight’s Star Lily’:

Mote by lingering mote, I accumulated my private cache, a special collection to contemplate at my leisure, strewn on a carpet of petal drop, besmitten in opulent thrall of cosmological wildfire, narcotic regeneration, incidental catharsis. Sleep ceased to be a requirement.

The above passage is a good representation of what the reader can expect throughout – imagistic, descriptive, narrative, vocabulary stretching but not building. I struggled to isolate a favourite or a particularly bad piece in the whole of Floribunda. There is a commendable consistency of voice within each poem and in the collection as a whole. Indeed, Gibbins excels in the evenness of his poems.

Without a jagged defamiliarisation though at the level of both poem and collection, which forces the reader to slow down, one may indeed only pass through fleetingly rather than be stopped in one’s tracks. It is not difficult poetry even though there are some $64,000 words. Once one has the keys one realises that the door has been wide open this whole time and that one need only step into the other room or through the French provincial bi-fold doors to the garden beyond. In other words there is some ‘there’ here, but one can only be charmed not challenged.

This aim, to represent the beauty of the natural world, to charm, reveals the nostalgia of Floribunda. It recalls craft, which is to say art as it has filtered down from the past avant-garde from on high and the product of hobbyists. In that sense it is craft in the sense of macaroni picture frames, CWA cake stalls and lawn ornaments made from spare car-parts. The absence of both the Indigenous and the eco-poetic is particularly noticeable.

The redemptive quality is in the relative comfort of this work. Everyone loves sponge cake. There were passages I wholeheartedly liked (‘jags and spurs interlacing above us’; ‘harried with clay clod’; ‘arcane phatasmic miasma’). It feels good to vacation in the Adelaide Hills with Morris and Gibbins; and one cannot help but appreciate the rhythmic quality of iambic pentameter. Interestingly though, the introduction notes that iambic pentameter is ‘a five beat line structure traditionally used for epic narratives’. Regardless of what one thinks of this, the aside seems to highlight a certain inconsistency, namely that these are thirteen (linked) small portraits, which might suggest that this form might not be the most appropriate to the enterprise if one accepts po-faced its historical limitations and expectations. The work is not epic, so why use a poetry device deployed in epic?

Floribunda will find its relaxed and comfortable home in people looking for well measured, rhythmic, consistent poems of place and nature. It appeals for its evocation of beauty, but this reader often longed for more.