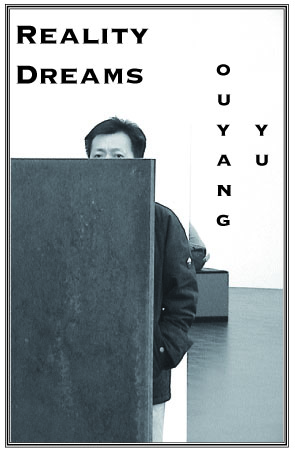

Reality Dreams by Ouyang Yu

Reality Dreams by Ouyang Yu

Picaro Press, 2008

The Kingsbury Tales by Ouyang Yu

Brandl & Schlesinger, 2008

While we awaited the arrival of Ouyang Yu's The Kingsbury Tales, a small treat came in the form of Reality Dreams. It is not at all surprising that Yu has put out two books of poetry in one year; in fact he has put out three, one written in Chinese. And that does not even touch upon his fiction and non-fiction. The man must be one of the most prolific writers in Australia. As is common in his extensive library of writing, both Reality Dreams and The Kingsbury Tales tackle cultural identity. But is this theme getting old? Have we had enough of the angry Chinese Australian poet grumping on about how dislocated he feels?

I actually can't get enough. Yu keeps his old themes fresh by attempting something new with each of his books. In Reality Dreams he works with the subconscious. Thematically, this works: a collection of confused and paranoid dream sequences from a man caught between two countries, two cultures and two languages, trying to come to terms with a bewildered sense of place and identity. Anyone familiar with Yu will probably get it, but those embarking on his work for the first time could become quite bored with the book, reading it as a routine exercise in surrealism, a simple collection of jottings from a man woken from his sleep – as in 'The dripping buildings':

Large stone structures

Red, lit from inside

I walk through

Down under

A vague awareness

Of celluloid hill

A man hacks at another man

Then at me

The other man becomes two

With a brandish of a broad kitchen knife

The entire collection reads as nonsensical and horror-driven. But if you look beyond the words and consider the foundation – what was brewing before the pen touched the page – then you see that each dream is a symbol for feelings of dislocation.

Occasionally we are stuck with an unfinished thought, a poem ending in a preposition or a conjunction, suggesting the dreamer / poet has lost his grip on the image, or its meaning, or, quite possibly, the English language to describe it, and so the poem becomes too convoluted, unable to continue on. In 'Shoes', for example:

Let me wrap it up here with this that when my head is submerged

in the morning tap water the lost reality returned

igniting those points of memory that

The dreams described here are variations of what we have all dreamt at one time or another; they express anxiety, fear and loss. Time and again, Yu returns to the classroom, where he is the teacher, and his angst seems to stem from questioning if his words (a chopped up Chinese version of the English language) are enough. His travel sequences work with the interchanging of river / boat and street / bus, suggesting a muddled sense of displacement. He panics over suicide bombers and Arabs, and why shouldn't he admit racial biases? Dreams have an honesty that can bring us to shame, and Yu himself has never shied away from honesty. Then there is the sex dream: the anonymous woman who gives him relief and the mysterious presence of a man, unsettling the liberation he was so longing for. In 'The woman who sucks on my tongue':

We are together

On the hill

From here I can see paths winding through tall grasses

Someone is going downhill

Someone is coming uphill

She points to another hill

Facing us from across a sea of hills

After she removes my tongue from her tongue

She tells me that he will soon be taken to a cage next door

And we shall be safe—

Whenever a figure climbs up the hill

Or goes down

She'll spit out my tongue

We stand there, like sentries

Like two trees

Mouthing each other deliciously

No entry yet

This is a fascinating collection, giving us more insight to Yu's ever-growing internal obsession, made external and accessible through his work. I see Reality Dreams, however, as a minor work, an addendum, one which assists in building this literary tower of a migrant disillusioned. Unlike The Kingsbury Tales, a major work; perhaps the climax of Yu's career thus far.

The Kingsbury Tales sets aside the subconscious and works from a very considered point of view. There are poems which allow us insight into an historical China while making the connection to a modern one – the romance gone, the dash to the finish line a ridiculous feat. There are poems which demonise the Australian tradition by painting an unenlightened canvas as a backdrop to a foreigner's journey. And that is what this book is: a journey. The journey of a foreigner, a migrant, an exile and a nomad. His name is O and he meets others like himself along the way, or others unlike himself who teach him more about himself. This work is much more personalised than its namesake, The Canterbury Tales, and is not so heavily sprinkled with laughter; so don't expect a solid comparison.

Though we are talking thematically about a loss of culture and familiarity, there is no sense of loss portrayed, nor is Yu in a state of confusion; nothing is romanticised. This is straight-talk poetry. No bullshit. Yu does not wish to demonstrate longing. He depicts anger. Rage against racism. Rage against language. Rage against China and her drive to be Western. Rage against Australia and her lack of drive, as evidenced in 'An Oz Tale':

Australia when you have lived him/her

Is an unpublishable piece of documentation

Of mediocrity kept alive as a national treasure

His negativity can be overbearing and occasionally borders on tedious, which is why I found the ending to this work unstimulating. I was surprised to be left wanting from such an innovative and sharp work of art (though Yu insists with his opening poem that it is a novel, I am reticent to call it such, nor can I claim it to be a collection – I feel it lies somewhere in between). A common reaction to his bitterness could be 'then go home'. But as Yu points out again and again, there is no home. There is only temporary residence, which, to embellish, is to him a temporary life. I quote from 'Temporary Life, a Non-tale':

Heat on one side, cold on the other, a temporary life

Like a letter, opened for a while, read, then folded up

Put back into the envelope, to be mailed again

Poetry's prime concern is language and Yu holds a very unique stance in this regard. As he writes in 'The Mathematical China, a Statistical Tale':

The number of ex-Chinese poets writing in English while living in China: 1

I presume the one to be Yu himself. Language is as interchangeable to him as home. He takes it another step forward and melds the two together, creating a sort of liminal space (one which mirrors the between-space of his home) with phrases like 'his woman boss grows fidgety with him for not hardworking enough' ('Dirt Cheap 001'). Broken English is real, so why would should it be ignored? And yet Yu goes even further in creating his own words: 'democrazy', 'deathtination' ('Defecting to China' and 'Slow Things Are').

Yu is beautifully situated to point out the absurdity of translation and the English language. For instance, English is 'Anguish' on the newly arrived tongue ('New Accents'), pointing not only to the folly of an accent but also to a lesson hard learnt. He plays on the (con)fusion of 'I' and 'you' as often English speakers use 'you' to refer to a generalised consensus, which admittedly refers to an inherent 'I' ('Getting Drunk at Midnight'). Anyone interested in linguistics will gobble this stuff up.

But will we find we are too full of Yu's pessimism to fully enjoy this feast on offer? Whichever way you lean, there is no denying this is an important work. Awards could be priming themselves for Ouyang Yu, just as critics could be having prosaic fits. Universities might be ordering copies while students aim for the free throw into the bin. Both threats and praises may be on offer, perhaps even simultaneously. The endless possibilities of juxtaposing views is because The Kingsbury Tales doesn't sit comfortably in the tradition of Australian poetry. That is why we should be grateful that Yu has come along to challenge it. What it means to be Australian is something entirely different in today's world. Who is to say that we all feel bonded by our island-like border or our feelings of mateship? Not Yu. Certainly not Yu.

Heather Taylor Johnson holds a PhD in Creative Writing and is a poetry editor of Wet Ink.