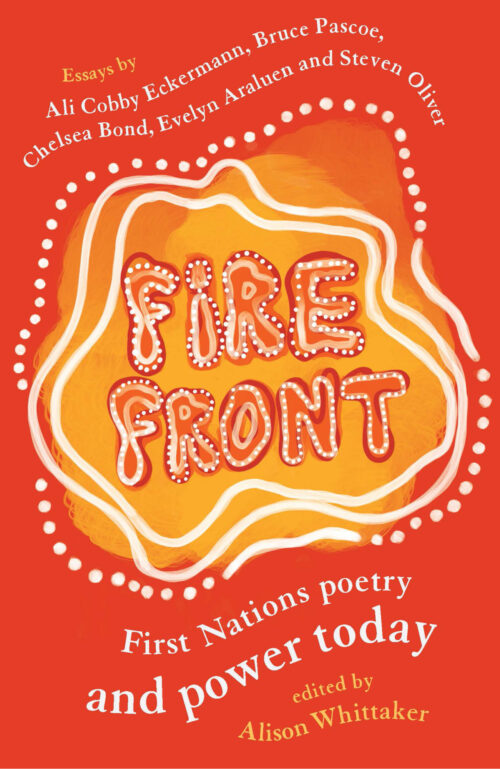

Fire Front: First Nations Poetry and Power Today

Fire Front: First Nations Poetry and Power Today

Edited by Alison Whittaker

University of Queensland Press, 2020

2020 is a hectic year, ay? Severe bushfires, Covid-19 outbreak, the subsequent lockdown, the colonial government funding an idolised re-enactment of the starting point of the invasion of these lands, Black people being harmed and murdered by state agents such as the police and those same police protecting boring statues of colonisers all while Rio Tinto destroys a 46,000-year-old sacred site.

However, watching Country being destroyed is not new for us First Nations people in the colony. Neither are new diseases, the glorification of a violent history or experiencing violence by the hands of the state. We’ve had 232 years of ‘hectic’ years.

For this reason, Fire Front: First Nations Poetry and Power Today, a collection of 53 poems which have been previously published and/or spoken between 1964 and 2019, feels extremely relevant in 2020. It’s as though they were presciently written in response to this year’s events. But if this anthology seems timely, it’s because many of the poems in Fire Front are timeless – they are part of a continuum of First Nations storytelling that has existed here for millennia. This storytelling has connected us to Country, our ancestors and kin since time immemorial.

The poems and essays that make up this anthology are also part of a long-lasting resistance to the colonial invasion of these lands that has continued since James Cook’s boat came to these shores. They are part of a collective refusal to be silent in the face of colonial forces desire for us to be gone.

Fire Front will always be relevant, at least for me (and maybe many First Nations readers like me) no matter what the year because of the Blak love and wisdom that exists within its pages. We will often have the desire to feel the strength of words it contains, like feeling the heat of a campfire on your face.

As an introduction to some First Nations poetry, Fire Front, curated by Gomeroi poet and law scholar Alison Whittaker, creates space for rethinking our world and sparks the imagination on what could be. For non-Indigenous readers, a collection of this introduces them to voices that challenge their world view. This could be a catalyst for these non-Indigenous readers to reflect on history, the violence of the colonial state, on nationalism and on themselves.

This reflection should include considering how humanity’s role as part of the environment around us could be different. What cannot be overlooked in this consideration is how our First Nations people’s connection with Country has sustainably and holistically ensured the mutual health of Country and us since time immemorial. This connection is constant: all of what makes up Country is our kin and Ancestors. We ourselves are Country. Many of the poems within Fire Front illustrate this connection by conversing with place and acknowledging and invoking the history and sentience of Country. This is compellingly exemplified in Lorna Munro’s ‘YILAALU – BU-GADI (Once Upon a Time in the Bay of Gadi)’:

THE LAY OF THIS LAND, IF YOU CARE TO LISTEN WILL TELL ITS EXCLUSIVE STORY YIILINHI RED CLAY MULGUN JUBAGULLY THIS TERRAIN EVOLVED OVER MANY EONS AND IN A RAMBUNCTIOUS FLURRY

The violent theft of First Nations’ lands by colonisers over centuries has comprised trying to sever this connection. Colonisers have murdered us and removed us from our homelands, paving the way for industries such as Western agriculture and logging, just to name a few. The colonial state continues to undermine First Nations sovereignty to protect other extractive capitalistic enterprises, such as mining. This has contributed to and produced anthropogenic climate change that has taken place for the last 232 years, and will only get worse in the future. Any chance to rectify this needs to start by addressing ownership of these lands. Alexis Wright speaks to how climate change is a result of our dispossession in ‘Hey Ancestor!’:

You seem all radical, in a hurry. The environmental science people said that the freak storms coming more frequently are a consequence of climate change, but I think that your appearance is the result of those little pieces of paper telling lies about land ownership by people who don’t know your power. I suppose the ancestral story should look the way you have decided to show yourself, your powerful story of millenniums revealed in full swing.

The colonial violence we face is intertwined. There’s great sadness in watching this destruction to your kin, your Ancestors, before your eyes. You can sense this sadness in many of the poems in Fire Front, for example in ‘Municipal Gum’ by Oodgeroo Noonuccal:

Its hopelessness. Municipal gum, it is dolorous To see you thus Set in your black grass of bitumen – O fellow citizen, What have they done to us?

And in this passage in Claire G. Coleman’s ‘I Am the Road’:

My Boodja has been stolen, raped, they dug it up, took some of it away They killed our boorn, killed our yonga, our waitch, damar, kwoka Put in wheat and sheep, no country for sheep my Boodja My Country, most of it is empty, the whitefellas have no use for it Except to keep it from us Because we want it back, need it back, because they can I am the road

Pingback: #PoetryMonth with #RedRoomPoetry-Day 15 Fire Front – La Pluma Poderosa