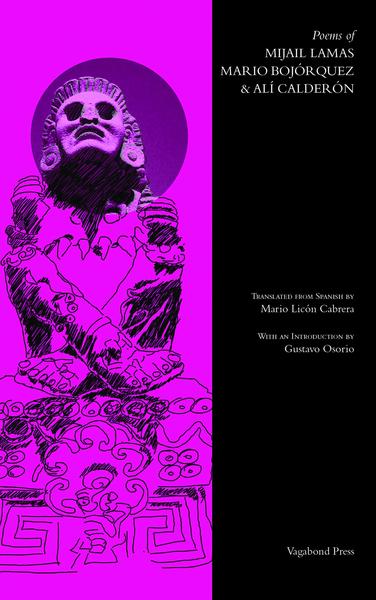

Poems of Mijail Lamas, Mario Bojórques & Alí Calderón

Translated by Mario Licón Cabrera

Vagabond Press, 2017

This year, Vagabond Press launched its Americas Poetry Series. The first volume in the series, translated and introduced by Peter Boyle, includes an eclectic selection of poems by Argentine poet Olga Orozco and Uruguayan poets Marosa Di Giorgio and Jorge Palma (Di Giorgio’s work is particularly exquisite; Vagabond has also published her last book separately, Jasmine for Clementina Médici). This second volume in the series, Poems of Mijail Lamas, Mario Bojórquez & Alí Calderón, focuses on contemporary Mexican poetry. It is translated by Sydney-based, Mexican-born Mario Licón Cabrera, a seasoned poet and translator. Licón Cabrera translates into both English and Spanish. He has translated important Australian poets into Spanish, such as Dorothy Porter, Peter Boyle and Michelle Cahill. Yuxtas (Back and Forth) , published in 2009, is his fourth collection of poetry, bilingual and self-translated. In 2007 he received a Developing Writers’ Grant from the Australia Council, and in 2015 he won the Trilce Award for Poetry. Licón Cabrera’s work on Poems of Mijail Lamas, Mario Bojórquez & Alí Calderón is a delight to read.

A translation has a dual nature, as product and process, verb and noun. The process always entails a balancing act between two cultures, which to a greater or lesser degree becomes apparent in the final text. That final text, again (perhaps evoking a Borgesian garden of forking paths), is two things at once: a variation, a transmutation of a preceding work, a text analogous to the original; and a new work in its own right. Thus, the process of translation is simultaneously a creative as much as an interpretative act.

This dual nature of translation becomes more pronounced when we talk about poetry, in particular the process of poetic translation. To translate a poem is to write it anew. A word can be worth a thousand pictures. This is the essence of polysemy, inherent to language itself, and one of the pylons of poetry. This is also what makes it devilishly difficult to translate poetry. Every act of communication entails losses and sacrifices, and translation is not the exception. But in poetry, polysemy is accentuated in a way it usually isn’t in everyday language, which makes those losses and sacrifices of translation much more dire. And so, halfway through the balancing act of cultural mediation between two linguistic and cultural codes, the translator of poetry is thrown that charged ball of polysemy. And they’d better not drop it!

Poetic translation may be devilishly difficult, but not impossible. In his famous essay ‘Translation: Literature and Letters’, Mexican Nobel Laureate Octavio Paz argues that the translator’s process, when it comes to poetry, follows a very similar path to the poet’s, but in the opposite direction. According to Paz, the translator:

is not constructing an unalterable text from mobile characters; in-stead, he is dismantling the elements of the text, freeing the signs into cir-culation, then returning them to language … The second phase of the translator’s activity is parallel to the poet’s, with this essential difference: as he writes, the poet does not know where his poem will lead him; as he translates, the translator knows that his completed effort must reproduce the poem he has before him.

This is what makes translating poetry doubly difficult: the poet writes with a compass, the translator writes with a map. The poet condenses meaning into text with the overwhelming freedom of their language, without a precise route to follow in that creative process. The translator must then follow that path trodden by the poet but with new hurdles, with rivers that have changed their course, shifting forests, collapsed bridges and newly built ones. The poem must be reproduced in a different linguistic world, bound by new semantic, metric, syntactic and phonetic conventions. This is partly the reason why most translators of poetry tend to be poets themselves.

Thus, the titanic task of translating poetry, which Licón Cabrera brings about with elegance and remarkable subtlety in Poems of Mijail Lamas, Mario Bojórquez & Alí Calderón. The majority of the anthology is dedicated to poems by Mijail Lamas. Born in Sinaloa, a neighbouring state to Licón Cabrera’s own Chihuahua, Lamas is a well-known literary critic, poet and translator (he translates from Portuguese into Spanish, most notably the works of Brazilian poet Carlos Drummond de Andrade, and Portuguese poets Mário de Sá-Carneiro, José Régio, Cesário Verde, and Portugal’s greatest classical poet, Luís Vaz de Camões). The subject of his poems in this anthology focuses on an exaltation of the mundane – a pen, dust, a childhood street, the scorching, ever-present heat of his native Sinaloa, which:

melts ideas turn dry your gaze wets the van’s interior the seat’s vinyl melts your back.

Lamas’s imagery evokes the works of Juan José Saer, one of the titans of twentieth century Argentine literature. Saer is famous for his profoundly lyrical prose, which in the most Shklovskian sense has an unusual talent for defamiliarising the ordinary. Something similar happens with Lamas’s imagery. A good example of this appears in the following lines in the sequence ‘What Used to Be a Desert’:

You drop the pen you’d grabbed to write that which you’re not able to fix, in silence you turn off one by one the house’s lights yet the unrest doesn’t stop completely.

We see a similar approach in another sequence ‘The Charred Shadow’:

I ran away from the sun until I found a place where in a bad mood and for a low price they offered me a table to write on, a cup of coffee and a bubble of air conditioner.

There is a strong longing and melancholy associated with that sublime approach to the everyday, a constant rumination on the evanescence of memory. The poems in the sequence ‘Part of You Returns Without Permission’ and ‘Like Something Extinguished by Fire’, play with these ideas:

I remember my first childhood home and the second and the third. They all are one, ablaze.

Mario Bojórquez’s work runs along very different lines. Like Lamas, Bajórquez is from Sinaloa. He has received numerous prizes and recognitions, including Mexico’s most prestigious prize for poetry, the Premio Bellas Artes de Poesía Aguascalientes. Much of the imagery in Bojórquez’s poetry comes from myth. ‘The Cyclads’, for example, references the Greek archipelago in the Aegean Sea, which includes the island of Delos, the mythical birthplace of Apollo and Artemis:

We sail the waters of an uncertain twilight the keel brakes the sharp waves Under the ocean’s surface some fingers sink in a different naked time.

His poetry is emotive, in a very visceral way. Such is the case with ‘Hymen’, reminiscent in its primitive allure of the opening bars to Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. The poem incorporates the famous exclamation of Carl Orff’s ‘Veni, veni, venias’ from Carmina Burana: ‘Hyrca, hyrce, nazazaz / trillirivos!’ ‘Sibila’ is a powerful blank verse septet that references the ancient Greek oracles, the sybils. The selection of Bojórquez’s poetry includes a collection of ‘shadows’, a sequence with strong Jungian undertones that touches on different aspects of the shadow archetype. There is also a sequence on deserts, which evokes different facets of solitude and loneliness: ‘Desert Birth’, ‘Desert Sun’, ‘Desert Room’, ‘Desert Exile’, ‘Desert Shadow’, ‘Desert World’:

The breath of dawn ascends over the dunes The morning light shows the ever quiet shadow of the path Silence grows in an endless symphony Plants and rocks beat a restless inner life Only men are amazed by their own bodies.

Interestingly, the desert sequence also includes ‘Dispatch for Czeslaw Milosz’, an homage to the Polish Nobel Laureate, poet and polymath, whose works often incorporated the desert motif.