Infantilisms by Louis Armand

Infantilisms by Louis Armand

Puncher & Wattmann, 2024

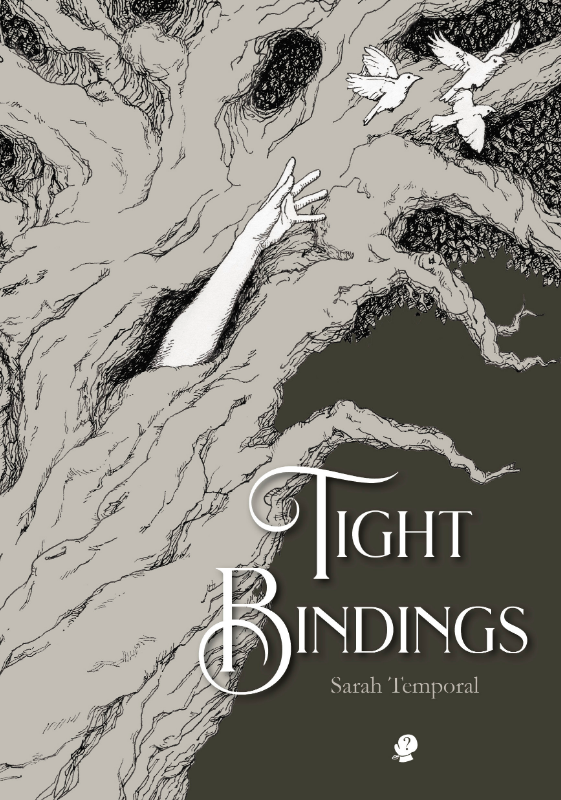

Tight Bindings by Sarah Temporal

Puncher & Wattmann, 2024

Louis Armand’s Infantilisms and Sarah Temporal’s Tight Bindings (both Puncher & Wattmann, 2024) are disparate collections which overlap in their ability to make the parts speak for the whole. Armand’s, in a resistant, disjointed way — allowing the reader to locate cultural, social, historical webs and associated meanings, or just stray off onto rich tangents of their own. In Temporal’s, we’re more gently guided, with its through lines of fairytale, nature (in its various forms), the body, birth, and concepts of girl, daughter, mother, woman.

How to write about Armand’s Infantilisms? About poetry that defiantly wriggles away from being apprehended or at least reduced to singular resonance or meaning? Armand’s large collection of poems has both width and depth and resists linearity. It’s a book you could pick up and scrutinise (rather than ‘absorb’) one poem at a time over months or even years. I found some poems (such as ‘Das Selbstporträt,’ 23) inviting in their rich mystery; others (due to a combination of tone, grammatical de-structure, and syntactic inscrutability) almost kicked me off the page. Armand is a writer, visual artist, and director of the Centre for Critical and Cultural Theory at Charles University in Prague, and the Centre’s interests, evolved “from linguistic structuralism and semiotics,” give me some clues to decisions around form and theme, particularly post-structural interests. A reviewer has responsibility to draw together common features of the poems in the collection, to give an overview, and I’ll do this here, though the collection resists it. I will zone in on some poems to explore their rich play, as this may help potential readers know what they are in for.

Some poems in Infantilisms are concerned with poetry itself and the role of poetry and the poet. The word “poem” or “poetry” often comes late in a poem, muddling the meaning we may be already leaning toward. In ‘Riot at the Hydromajestic’ (77), “the poem” comes in at the last line, complicating a connection between the Turner painting The Fighting Temeraire “halfreflected” in a bar, a barman, “three versions of the protagonist in a lifeboat”, and a possible narrator. In the line, it seems desolation (almost as an additional subject because whose desolation? we do not know) is “ready to leap from the poem’s last line & abandon everything”. Another poem that mentions “the poem” is ‘Statue of Svatopluk Čech, Pond w/ Fountain’ (113), in which “the poem defies gravity insouciant / as a waterspout”. This is nine lines deep with no foreshadowing, and continues “here the bounding black wolf-pelt muzzles the ball. / all for the joy of repetition / & repetition for all!” Which is quite funny, even if the meaning slip-slides away from you.

‘Apophenia’ (54) means the way humans seek meaningful resonance in patterns of unrelated or random objects, data, or ideas. I wondered, is Armand insinuating that the poem itself can throw together unrelated data in the form of unlinked words and/or sentences, references, quotes, and more, and a human will seek in it a pattern? Is the seeking of the pattern an infantilism (humans being an infantile species) or is the infantilism the writing of the poem and the belief that play produces unexpected meaning?

There are boats and ships in the collection, and oceans, seas, rivers. I sometimes connected this to the references to poetry, as vessels on a surface (or on depths: “A sea without chairs” in ‘Beckmannesque’ (25)), deliverers of something (including dominant and colonising somethings). Or the vessels carry us, in the poem, from one time frame to another. In ‘Confessions of Living in Fire’ (84), the final stanza begins,

And though it has many eyes some of them must sleep – intoxicated by rainfall & beautiful sinking ships & all tomorrow’s just conditions.

The final line of this follows that temporal transportation via “sinking ship” with one of what I came to think of as Armand’s micro–epics: “There’s writing on the wall, too” (which can be read both literally and as the expression, originating from the Bible, that prophesies an ending). There are passages in the poems other than across water. The parts of the body I noticed most in these poems were those that substance (food, voice, breath, sound) passes through: throats, lungs, ear canals.

Armand’s grammatical deconstruction, or what I thought of as ‘syntactical halts’, are often related to subject (in the sentence structure sense) shifts or open ends, pronoun confusion, tense shifts, alternating points of view, temporal illogic, and changes between past and present participles. Landscapes and buildings and other non-human objects are also subjectified (e.g., the skyscrapers in ‘That Perilous Night’ (51), which “leap / black arrows & hands / mysteriously from darkness”) and this can stop you short. The fascinating effect of these ‘halts’, for me, was of the brain trying to circle back in on a logical follow-through; struggling to take in the additional, twisting information; and then a kind of frustration when the conclusion never arrived. It’s worth quoting more of ‘That Perilous Night’ at length to give an example:

I reached the conclusion that

several winters’

contemplation boxes

knotholes

of infectious activity

plotting revenge

but if you don’t change yr mind

about past art

as an advertisement of all that’s sick

like stopmotion war footage

or America

or unbreathable 4-colour separation process

Other layering to be found includes that on pandemics and lockdowns (e.g., ‘Custodial Sentences’, 86); speculation and dystopianism, almost pulpy at times (‘Vague Germs of the Unknown’, 22); and references to God/gods and other faith figures and items, as much as references to science, which makes me think Armand is concerned with mystery — that being a property, too, of the discombobulation of deconstruction. The poems are highly intertextual and many are for, after, dedicated to, in memoriam of other thinkers, poets, artists, cultural figures. The spanning of pasts and futures is often done materially — I’ve mentioned boats but there are fossils, formations, through to space junk. The word “cosmic” crops up and the collection does have spatial, along with temporal, dimensions.

Though the form of the poems varies massively — from a six-word poem (‘Quixote’, 67) to a rhyming poem (‘Gulag Blues’, 83) and everything in between — several poems have a similar kind of movement. It’s a mix of containment and explosion, of the aforementioned micro and the ‘epic’. Sometimes the movement is like this, as in ‘The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife in the Mind of the Fisherman’ (36–7): We’re in always/the before (“always voices whispering”); then there’s one event/moment (“the monster […] / slipping through nets”); the habitual tense comes in (“The days, he came to believe, weren’t long enough”); and then we’re hurtling towards (“Dark energy accelerating the universe”); then there’s moment, moment, moment, moment; and finally a conclusion/projection/future encroaching (“Well every American president / deserves to go hungry at least”). One of the most epic endings could be this one from ‘Monet, Trouville’ (92):

[…] what’s history? Turned by unoiled wheels that shriek in a night smothered by cretaceous foliage – contemplating the evolutionary lilypond.

Perhaps what I mean by epic is ‘all-encompassing’, or maybe ‘panoramic’ (but temporally as well as spatially).