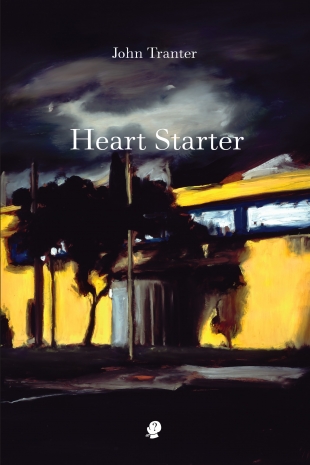

Heart Starter by John Tranter

Puncher & Wattmann, 2015

What is more old-fashioned than modernity? New York in the 1960s; Paris in the 1920s; Edwardian England: how entranced we are by the bygone milieu of modernity. John Tranter has long appreciated the poetic potential of the almost-new, almost-old, as seen in his poems on movies, jazz, the New York School, and so on. But as seen in his latest book, Heart Starter, his interest in such things is not merely nostalgic. Rather, his work is obsessed with remixing the magic pudding of modernity. The past, in other words, is there to be used, not revered or sentimentalised. Tranter’s poetic revisionism treats source texts and forms as transitional objects (to use Winnicott’s term) that offer open-ended play and creativity, rather than demand compliance.

Heart Starter, Tranter’s twenty-fourth book of poems, is notably proceduralist in its literary revisions. Its first two sections are made up of poems ‘related to’ The Best of the Best American Poetry (2013) and The Open Door: One Hundred Poems, One Hundred Years of Poetry Magazine (2012). These poems are ‘terminals’, poems that borrow the end-words of each line of their source poems. The terminal is a form notable for its absence of conventional formal markers (with predictable stanza form and line-length being the most obvious absences). And while rhymes can appear, these are from the source poem; there is no ‘rhyme scheme’ as such. By employing fragments of pre-existing texts to generate new texts, the terminal is by definition endlessly shape-shifting, and therefore paradoxically ‘formless’. As Brian Henry points out in his 2004 essay on Tranter’s terminals (originally published in Antipodes and available here), the terminal is both constructive and destructive, and knowing or not knowing the source poem is relevant to any reading of a terminal, since ‘the terminal can respond to, contradict, imitate, parody, or do its best to ignore the source poem’.

The American anthological provenance of Tranter’s source poems in Heart Starter suggests something of this complex relationship to a terminal and its source. Responding to more-or-less canonised American poems is an ambiguously postcolonial strategy for an Australian poet, engaged as he is in acts of homage and subversion, comic destruction and serious reconstruction. The beauty of the terminal is that each instance of a terminal allows any or all of these attitudes to be evoked within the new poem. ‘Small Town’, for instance, uses a poem by that elegiac American poet, Anne Carson, to present an elegiac vision of ‘the Small Town of the Empty Windows’. ‘One Variation’ is a mordant variation of the final section of ‘Eight Variations’ by that great poet of mordancy, Weldon Kees. ‘Doting on Blubber’, one of a number of poems whose title comically refers to its source poem or poet, takes Mark Doty’s ‘Difference’ to produce a poem on jellyfish and language, the subjects of Doty’s poem. But Tranter’s poem, in its attention to form and formlessness, strikes me as not only concerned with its subjects, but also secretly self-reflexive, given the formless form that it is using.

As these poems show, then, even the most seemingly arbitrary constraints can be creatively enabling. (Rhyme is a traditional poetic example of the creative potential of an arbitrary constraint.) And while the end words of each line – and the number of lines – are predetermined for any given poem, Tranter, as he points out in his Preface, happily ignores those constraints if need be. As Shakespeare’s famously ‘flexible’ blank verse shows, such an attitude is also authorised by tradition. One of the pleasures of reading such work is seeing the ways Tranter’s own poetic personality emerges from the host poem, like something from a science fiction movie. I am far from familiar with all of the poems Tranter uses for his terminals, but of those I am familiar with, only one, Donald Justice’s ‘Men at Forty’, seemed to overpower Tranter’s terminal, perhaps because the latter seems too close in tone to its original.

Heart Starter is rounded off by thirty-odd poems, most of which are sonnets that range from the Shakespearean to the Tranterian. A number of these poems brilliantly riff off ‘Voyelles’, the famous poem on the vowels by Tranter’s long-standing precursor-poet, Arthur Rimbaud. There is also a superb poem for the otherwise-ignored consonants: ‘B, brave brown, C, icicle, / Pendant, D, dun though pale, / F for faint mauve, fish and bicycle, / G, gothic paint in a green pail …’ Like any formalist, Tranter knows the comic potential of triple rhyme.

As all of this suggests, the idea that ‘the postmodernists’ find poetic form anathema is ridiculous. Poets such as Tranter are obsessed with form’s enabling powers, whether that form is ‘traditional’ (the Shakespearean sonnet) or ‘avant-garde’ (the terminal). But as the Shakespearean sonnet suggests, all forms were once nonce forms.

Formal issues aside (since no form can predict an actual poetic outcome), Heart Starter is notable for its Tranterian playfulness and humour. The collection is littered with jokes, such as ‘Sure, he’s a little self-forgiving, / who isn’t?’ (‘The Parkas’); ‘the nitty-gritty quiddity’ (‘Loxodrome’); and ‘How to end up with half a million bucks? / Easy: invest a million in publishing verse’. But there is a melancholy aspect to this collection, too, with a number of poems dealing with ageing, illness, and death. For instance, ‘Your Life’ is a picture of the afterlife, presenting ‘the end of old age’ as ‘not / teen fun in the back row of the local cinema / with a pretty girl and a bucket of Popcorn Deluxe’. This, and a handful of other poems here, are as bitter as anything Tranter has ever written (which is not to say they are confessional). But even when engaging the elegiac mode, Tranter usually retains a comic aspect. In ‘Loxodrome’, for instance, Tranter muses on the late Australian poet John Forbes:

If I wished hard enough, would John Forbes come back? He did in my dreams, but only to rectify a minor error of mine, and now I have forgotten what it was; a clumsy gesture in the Romantic mode, or perhaps asking for more, like Oliver Twist at the trough of verse? Or maybe just being clever but not clever enough, or far too sincere when sincerity comes in scare quotes and wearing jeans carefully not ironed but bleached in irony.

The collection, bleached in irony as it is, plays with all the registers of sincerity. This tension between irony and sincerity is seen in the collection’s final poem, which appropriately enough is a deformed form – a rhyming couplet threaded out to twelve lines – delicately satirising the pursuit of poetry.