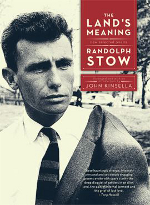

The Land’s Meaning: New Selected Poems by Randolph Stow

Ed. John Kinsella

Fremantle Press, 2012

I have nothing to say about poetry in general (except that mine tries to counterfeit the communication of those who communicate by silence). And these poems are mostly private letters – Randolph Stow

And if they should ever tempt me to speak again,

I shall smile and refrain. (‘Landfall’)

In his masterful and extensive introduction to The Land’s Meaning: New Selected Poems John Kinsella, who edited the volume, writes that much of Randolph Stow’s work is metaphoric, weaving things together in a way that promises narrative but actually reveals very little. Reading through this new selected poems, I was struck by the tension of poetry as public utterance of private speech, which characterises Stow’s work. Whether dealing with myth, landscape, colonialism or love, these are poems that are selective in what they choose to reveal and particular in the techniques they use to reveal. It is no surprise then that in the composition of this volume Stow limited the poems which were available for republication. As the volume stands, at only 120 pages, it is slim for a collected works but, as Kinsella notes, the breadth of the poetry it contains speaks to a much wider oeuvre; this volume does it justice, collecting together Stow’s poetry with his libretti and some well-chosen sections of his prose.

Spanning some 60 pages, Kinsella’s introductory essay is one of the joys of the volume. Respectful of Stow’s personal reticence, Kinsella locates and explicates the poems selected without much reference to biography. In Kinsella’s rendering this poetry appears to be haunted by a variety of ghosts, where what has prompted Stow out of his natural silence is a need ‘to proffer alternative ways of seeing and articulating a crisis he found too disturbing to leave unsaid, but still did not want to articulate specifically’ (15). Kinsella speaks here of the crises and ghosts of colonialism that populate Stow’s work, which Stow addresses most directly in the longer poem ‘Stations’, in which ‘The dark women go down to the haunted pool./They speak to the children, the spirits, the yet un-born’, and later, ‘The dark women come up/barren from the dark water. The spirits die.

Viewed through the lens of the entire selected works, Stow’s haunting is much too complex to be simply tagged pastoral or colonial. We can perceive this in ‘Stations’, which in title and in diction directly interrogates how the Judaeo-Christian mythos intersects with the process of nation-making that he is both invested in and critical of. He writes ‘I am the third begetting of my blood/to work these acres no one worked before us’, and ‘This was not in the dream my generation/dinned in my ears. This was not in the legend.’

Legend and myth reoccur throughout the selected works but are never simple, and his treatment and questioning of them is richly rewarding to the reader. The collected early poems that open the volume are largely dislocated from the landscape that we expect in Stow’s poetry. Instead they are songs in a chorus of voices, none of which seem to be the direct lyrical ‘I’ of Stow. Music roots these poems, as in ‘Chorale for the Death of Icarus’:

But he has wings, and is pursued with light. Golden he lies, and he has brushed the sun’s fire in his flight. We saw him rise from the east sea, a wound upon our sight; dawn was across his wings, and midday in his eyes.

Stow is always conscious of the origin of poetry in mythic song. Throughout the collection he makes repeated use of refrains, as in the early poems ‘Country Children’ and ‘As He Lay Dying’, which repeat their opening lines throughout. Refrains in these poems operate on two levels: they suggest an obsessive return of a mind to a particular subject, and they also make us conscious of poetry as a collective ritual that is composed and enacted. Song becomes one of the ways in which Stow is able to reveal his personal obsessions, while simultaneously maintaining distance from them.

Entering Stow’s more familiar work of ‘Outrider I’ and ‘Outrider II’ through these early poems, the threads of myth, and specifically the relationship of myth to history, are brought to the surface. The specifically Australian characters of many of these poems speak and are spoken of with the same musical dexterity and distance as Icarus. For example, there is ‘Harry, who has two squeeze-boxes, can yodel/high as the sun. His music is the spheres,/and earth, and all earth’s tears’ (‘In Praise of Hillbillies’), and in the title poem ‘The Lands Meaning’ we meet ‘one-eyed Mat, eternal dealer in camels’.

But in the poems that speak directly to and about the landscape, a struggle emerges between Stow’s impulse to construct the land as a mythic figure and imbue this ‘new’ nation with meaning, and his acute awareness of the ills of colonisation. Stow uses his ancestral tropes of western, and at times eastern mythology (Kinsella deftly unpacks Stow’s relationship to the Tao in his introduction), so that myths become another type of ghost in these poems. In several poems this is related back to an ability to map or name. In ‘The Lands Meaning’ we have ‘one who has returned, his eyes blurred maps/ of landscapes still unmapped’; in ‘Strange Fruit: ‘Did we ride knee to knee down the canyons, or did I dream it?/They were lilies of dream we swam in, parrots of myth/ we named for each other, since no one has ever named them…’ In ‘At Sandalwood’ there is ‘the crow’s voice in the empty hall of summer/ joins sun and rain, joins dust and bees; proclaiming/ crows are eternal, white cockatoos are eternal:/ the old names go on.’ Again, we see silence and reluctance to speak filtering through these poems, maintaining distance between the speaker and the land, and the speaker and the reader.

Pingback: Randolph Stow Research Materials - Writing NSW