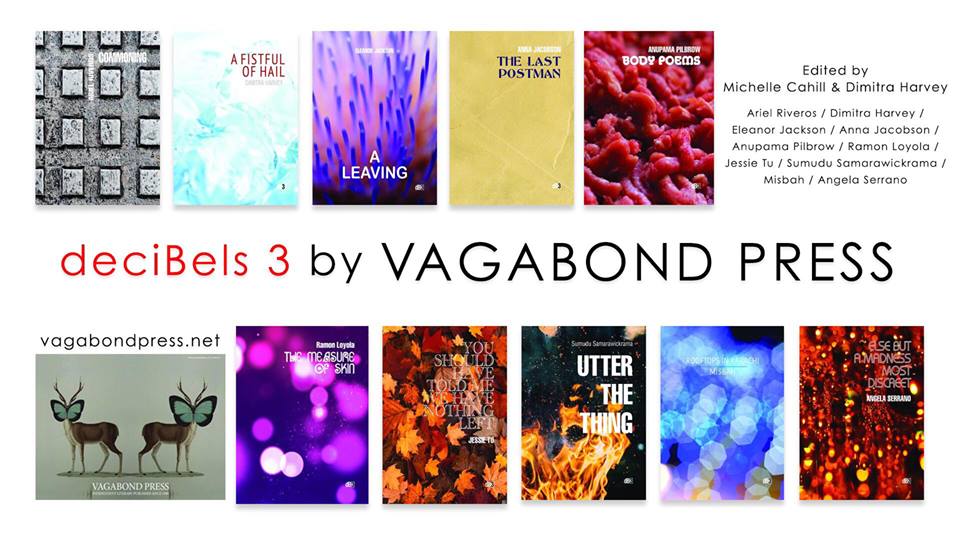

deciBels 3 edited by Michelle Cahill and Dimitra Harvey

Vagabond Press, 2018

Poetry as a form permits one the ability to see, touch, bend and examine the human experiences that we may find elusive. All of a sudden, the glances from others we would have otherwise missed, start to make sense. Haunted words that follow us our entire life begin to destruct. And a voice that belongs leaps out of the page and into the world, leaving a roadmap to follow.

This process, a reader’s reckoning with her awakened self, may be colourblind. Poetry gives birth to intuitive knowledge, which is a powerful way to explore the subject of race. In her introductory note, series editor Michelle Cahill argues the importance of poetry that talks about race. She also highlights race as an entity moving within time and place, a function of what is real. Cahill concludes ‘that the value of a poet’s work is largely transacted by their identity, whether that is visible or whether it is concealed’. As such, her series celebrates ten exceptional poets whose poetic voices illustrate a redemptive focus away from the concerns of the dominant power. They invert that power through poetic disruptions, and not of race but also gender.

Cahill has collected poets whose cultures and languages trace to South Asia, the Philippines, Greece, to the Jewish, Chilean, and Taiwanese diasporas of the world. They have in common a tendency to choose realism, in which identity is expressed unapologetically and in conjunction with the universally charged experiences of life: loss, loneliness, mental health, sex, love and grace.

Jessie Tu’s collection You Should Have Told Me We Have Nothing Left is a visceral body of work that finds acceptance of the drama of life, which is filled with the voices of everyone else. Tu’s candour speaks to the way life forces us to sober up if we are to survive. In her poem ‘And It Is What It Is’, she illustrates the intersections between gendered conditioning and the universality of sexual desire:

Mother told me to slip through like a good girl so I take buses around the city to find the sunken bottom lip of your bitter tasting mouth

Tu seldom shies away from the empowering nature of sexuality, which is a level playing field on the page. This is further demonstrated through the poem ‘Almond Butter’ when the proclamation is made:

I am absolutely in favour of all kinds of sexual fetish, fart, feet, rings, clown.

All the while, Tu is exercising the complexity and mobility of what it means to be human:

I write because I am lonely for other lonely people. Not only does my loneliness rot but the fantasies I left during my life.

By comparison, the title of Sumudu Samarawickrama’s chapbook is demanding, almost daring the reader to Utter The Thing. The thing is what the reader must decipher, in plain sight on each page. Is Sumudu daring us to utter hate? Or is she directing us to find out how resistance can rummage through a burning building? ‘Foxes’ is a poem that feels like war and liberation simultaneously:

Give up on this supposed detachment There was a battle fought. Grasp the nettle leaves and the Chestnut husks. They are only conquered by force.

And what is more powerful than a force filled with the wisdom that evil consumes all? Like the rest of this collection, ‘Foxes’ is such a vessel:

But I’ve given up that dishonest detachment. Allow the fire.

Angela Serrano compliments the series with her collection Else But A Madness Most Discreet. It highlights the voices of grief, power, culture and destruction in stories from the fringe. In her poem ‘Sydney Road in 2011’ she articulates the darkness that lives around us, especially known to women:

Where catcalls of all sorts punch the mid-evening air, where contests of all sorts, between all sorts are the topics of chatter between slow sips of single origin coffee.