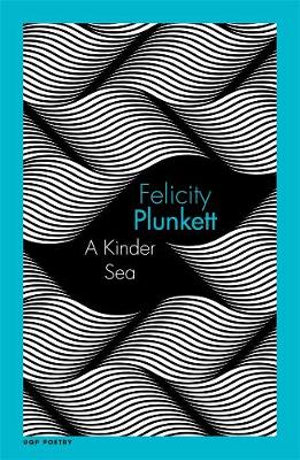

A Kinder Sea by Felicity Plunkett

A Kinder Sea by Felicity Plunkett

University of Queensland Press, 2020

The writer Phillip Hoare, celebrated author of The Whale and self-confessed sea obsessive, once wrote: ‘Our bodies are as unknown to us as the ocean, both familiar and strange; the sea inside ourselves.’ This quote might also describe acclaimed poet and critic Felicity Plunkett’s latest book of poetry, A Kinder Sea, which takes writing about the sea – or through the sea – to whole new depths. This collection of 29 poems, published by University of Queensland Press (2020), reveals more than just a fascination with the literal sea. As any seasoned ocean swimmer or sailor knows, a calm surface is no indication of the sea’s nature, or of one’s journey across it.

The cover, an exquisite Sandy Cull design, is as undulating as the sea itself, and the contents page reveals such oceanic titles as ‘Becoming the Sea’, ‘Underwater Caulking’ and ‘What the Sea Remembers’. They conjure up exploratory visions of the often-fatal human obsession with the sea – the sea as both grief and hope embodied, and as a locus of loss and longing. A Kinder Sea is all of these and more, dextrously rendered – for example, through Plunkett’s singular neologisms – but it is ‘the sea inside’ that is the collection’s focal point. We each have a sea inside, as Hoare muses, but when a person experiences hardship, grief and unspeakable loss, what becomes of that sea? And how does one keep from drowning? Plunkett seems to suggest that one way is to hold on to a craft, whether literal or metaphorical, as explored in ‘Becoming the Sea’. The persona is anchored by a craft of words, despite her grief:

I have unreeled sentences from my spine’s spool to free my bones: cast words into the depth of your response.

The long vowels and spondees such as ‘spine’s spool’ and ‘cast words’ make the lines sonorous, and the poem itself seems to ‘unreel’ on the tongue as a result. This kind of prosody is prevalent throughout the collection, lending it an aural beauty reminiscent of the lyric poetry of Sharon Olds, Sinead Morrissey and Tracy Ryan. Plunkett goes on to write: ‘I want my disappearance to be untranslatable’ – that is, paradoxically, untranslatable into language and difficult to articulate, which would be evidence of the depth of love. ‘Becoming the Sea’ is reminiscent of a key aspect of Plunkett’s award-winning debut collection, 2009’s Vanishing Point; her preoccupation with the extended metaphor of language as tangible and human physicality as linguistic. In that collection, the poem ‘Learning the Bones’ extends her father’s love of Latin grammar into her very being. She confronts her grief over his death by utilising this extended metaphor: ‘my hands writhed, alive – a tangle of nervous verbs / untranslatable’. Earlier in the poem, she writes, ‘my feelings’ syntax made no sense’. Plunkett’s poetry foregrounds the fact that often feeling is untranslatable, and that this a universal human difficulty, even for a writer of poetry.

In another poem from Vanishing Point, ‘After the Park’, a sort of sequel to Gwen Harwood’s infamous ‘At the Park’, Plunkett again renders emotion linguistic: ‘. . . my swollen skin, my ungrammatical want’. This technique is carried over into A Kinder Sea and works well in poems centred around longing and grief, such as in the affecting ‘Glass Letters’. Plunkett speaks of words as tangible things:

Shaken wordless, I wash syllables in salt, trace remembered promises to the place they rolled in foam.

Words become flowers: ‘froth-skirted roses in an old garden / each syllable discarding its petal / under my ribs’, part of the sky: ‘you / study clouds’ thesaurus for one close word’, and fabric: ‘knotted and frayed, our words / a smooth braid in sky’s hymnal’. It’s thrilling to see language conceptualised and crafted in this manner. Above all Plunkett is a word-lover, or collector of a ‘word-hoard’, as Seamus Heaney described the work of a poet, and this is evident throughout the collection. Her use of wordplay is particularly luscious in the poem ‘Syzygy’, from the book’s second section, where Plunkett seems to revel in adverbs:

Edge, swerve, disturb, you’re all verb: pressed to you, wilfully, irresistibly, like ivy, sighingly, I climb like an adverb unattached.

Another interesting aspect of Plunkett’s poetry is her propensity for neologisms – specifically, her coining of compound nouns, including kennings. This was a highlight of her first collection, which contained such gems as ‘whisperthrill’, ‘breath-light’, ‘love-warm’, and ‘violet-soft’. ‘A Kinder Sea’ adds to this lexicon. In the poem ‘Three’, she writes:

All threads in a weave of kin, all roots that take you down to glasswords sandbroken ground small beyond sound.

‘Glasswords’ could be a kenning for promises, for example. Like Heaney, Plunkett is drawn to this interesting Old English device, and the piece ties in nicely with the earlier ‘Glass Letters’, which makes a motif out of the idea of words being transmuted from sand into glass. Additionally, if glasswords are promises, then glass letters might be the specifics.