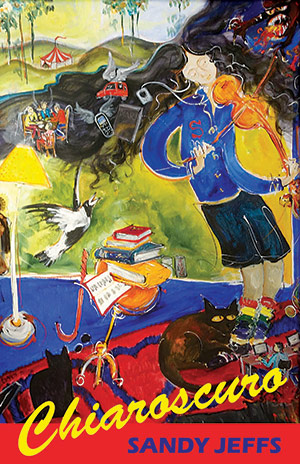

Chiaroscuro by Sandy Jeffs

Black Pepper Publishing, 2015

In her poem ‘The suicides’, Janet Frame writes: ‘know they died because words they had spoken/ returned always homeless to them’. Perhaps more deaths could be prevented if people were able to speak without fear of being shamed or ostracised, knowing that their words might lodge in someone’s mind or heart, and that language, if wrestled with, could offer healing.

Poetry – confessional poetry in particular – offers a safe forum for the frank translation and exploration of mental illness, as spearheaded by American poets of the sixties such as Anne Sexton and Robert Lowell. In Australia, Francis Webb, Bruce Beaver and Kate Jennings, to name a few, furthered the style. One thinks of Webb’s sequence ‘Ward Two’, intimately detailing his and inmates’ lives, and Beaver’s ‘Letters to Live Poets’, unflinching in its capturing of both inner and outer processes of madness.

Sandy Jeffs is a Victorian poet writing within this lineage, whose first collection, 1993’s ‘Poems from the madhouse’ (which won the Anne Elder Award’s second prize and a Human Rights award), aimed to give the reader direct insight into the florid thought patterns of a schizophrenic mind, forgoing the restraint of Webb and Beaver for a rambling transfusion of desperate words, and utilising startling, grandiose imagery. It is the struggle to convey her illness through a slippery lexicon that sets the groundwork for later poems. Her second book, ‘Blood relations’, published in 2000, saw Jeffs tackle her traumatic childhood, moving from mind to past. She invites us to see the connection between the two, as she recreates the pain of domestic violence. Despite the horrors, she remained hopeful, feeling strength in knowing ‘that was then’, moving forward by exorcising such demons through poetry.

In her latest collection, Chiaroscuro, Jeffs is notably restrained and deliberate in her choice of words, indicating that she has become comfortable with language. The title refers to the use of contrasts between light and dark, and she conveys this continuing, if less horrific, struggle in the title poem:

… in the house of mirrors a bewildered face illuminated by darkness and shrouded in light peers back at me

She implies that you will uncover her true self through her more sombre words, which will ‘illuminate’ her, rather than through the mask of happiness she may wear outside of her writing. Jeffs also writes about poetry, a tricky area, since such poems can suffer from generalisation. The process of writing poetry must have a redemptive, spiritual presence in her life, and there is a personal magnitude that can only be conveyed through hyperbole, such as in ‘The hour is striking’:

The hammers and anvils are pounding. Her foundry is casting its metal. The zephyr is turning into a gale. A poetry storm is brewing

There is also the overwhelming sense that Jeffs is now joyous with language, where in earlier collections there was a brooding mistrust of it, of whether it could hold her suffering. She is grateful for the words that find her, knowing that, due to her mental illness, her brain may turn against her the next day, but it is a universal feeling, for all who experience writer’s block:

Words are flying into the air and falling madly upon a page. I seize this hour. There may be no poetry tomorrow

It is in her satirical poems, however, that we find Jeffs at her strongest, such as in ‘Hermione Beecham-Smith counsels J. Alfred Prufrock’, a critique of T.S. Eliot’s infamous persona:

J. Alfred, you can’t go on like this you need therapy your indecision is paralysing you just pop the question. Who cares if you are growing old and balding

It is tongue-in-cheek advice from one who is well seasoned in experiences of psychiatry and counselling, a 21st century reaction to the mental instability inherent in this cornerstone of modernism. Jeffs is not afraid to question such holy cows, and in ‘Durer’s St Jerome in his study’ she dissects the bible in a Wilde like manner, through the voice of St Jerome:

… I would suggest a major rewrite to make it a more coherent narrative … To be honest, in my humble opinion I think The Bible is beyond salvaging even with my considerable editing skills. I cannot recommend it. I simply can’t see it being a bestseller.

It encourages us to look more critically at all texts we read, and indeed at the application of language itself, when it is taken for granted. In a time where people are still fighting religious wars, it is pertinent. Elsewhere, Jeffs unpacks the romanticisation of war that still exists both in this country and overseas by responding to the advertisement ‘Daddy, what did you do in the Great War?’ with a biting dichotomy of a sergeant and his recruit, the lines mirroring each other as they unveil corruption and abuse:

Well, darling, I saw the young men come into bootcamp and being their sergeant it was my duty to turn boys into men into fighting men, you know so me and some mates initiated them by shoving a broom handle up their arse forced slops down their throat ‘Well, darling, first I went to bootcamp I was taught how to kill then I was bastardised by me superiors they shoved a broom handle up me arse forced slops down me throat

In other poems she comments on the commoditisation of celebrity, the economic market, the growing presence of the Internet, the philosophical dilemma of buying poetry over a Big Issue, and even ‘poetic license’ itself. In these tight, vernacular poems she displays the same candour but in a critical, amusing light. The poems are less rambling; they are sharp and humorous, despite the dark subject matter, as she surveys the contrasts of her own personal chiaroscuro.

It is safe to say, with this third collection, traversing social awareness, disarming wit and exuberant use of language, that the strengths overcome the weaknesses, and that Jeffs’s words will always find a home.