Archipelago by Adam Aitken

Vagabond Press, 2017

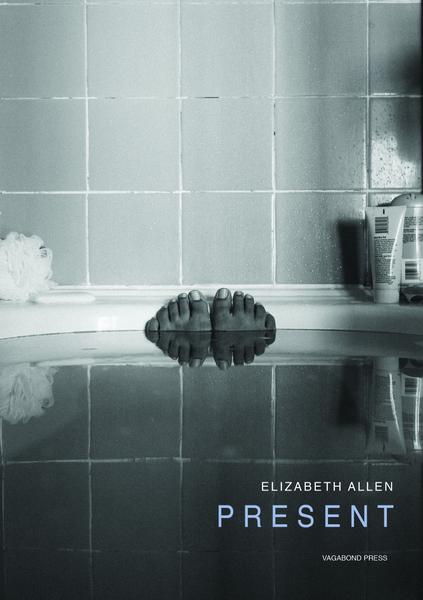

Present by Elizabeth Allen

Vagabond Press, 2017

In a judicious review of two ‘lucid and intelligent books’ on the job of the literary critic* and of a new edition of Eric Auerbach’s Mimesis, Edward Mendelsohn argued against the essential nostalgia of criticism in favour of a version of Kant’s ‘universal subjective’: finding ways to cross ‘the disputed border between popular and elite culture … without pretending it doesn’t exist’. One of the recurring negotiations for the critic – and, I would argue, for the poet – is the difficult business of intimacy: how to inscribe the subjective as both ‘confessional’ (and ‘lyrical’) as well as observational, satirical, evaluative.

These two very different collections from Vagabond Press offer tangential, engaging and verbally sinuous takes on this interplay. Adam Aitken’s Archipelago dramatises consciousness as a scattering of (dead?) islands – the cover image shows famous graves marked by numbers (to which you need a key) in the underground city of the Cimetière Montmartre. The poems are ‘postcards’ of places in France (from Paris to Avignon), French art, writing and history; freewheeling thinking and memories, cultural commentary. The gods invoked and played with in Archipelago include Henri Rousseau, René Char, Gustave Flaubert, Arthur Rimbaud and Ezra Pound (that troubadour riff ). Aitken’s perspective is ‘cool’, ironic at a playful, postmodern distance. Elizabeth Allen’s Present, with its cover hommage to Frida Kahlo’s What I Saw in the Water suggests a more ‘felt’ concern with habitation, process, subjectivity. Allen’s poems focus on personal relationships, the dimensions and language of experience and affect. They present themselves as epistolary and confessional – like carefully sculpted journal entries. I am tempted to suggest the volumes embody the differences between the modernisms of Joyce and Lawrence, between observing and feeling, negotiating ‘popular’ and ‘elite’ in overlapping ways.

Consider Aitken’s ‘Lyric’ for example: ‘First there is the picking of a rose / then the theory of what it means; / … / First death, then empathy. / … / There are the interiors, / then the interiors of the interiors / and what comes between us / is precisely the subject of the poem / … / padded with medieval tapestries, / perhaps the mineralised torso of a God, / or even a country that can’t address us / as [it] lacks a studio or [eyrie]’. Pervading Aitken’s poetry is a sense of something almost confrontationally personal, kept at arm’s length by constant thinking, observing, wordplay, juxtaposition of contrarieties (for example, ‘death, then empathy’, above).

Liz Allen’s poems are often almost heartbreaking, with their crystal craziness and their just-so-ordinary, almost casual vernacular. The fine ‘Absence’ sequence apostrophises the concept in five definitional movements which are wry, but testify to intense sadness as well as defensive indifference. The first poem’s ‘frangipani tree / outside the window / that I will never see again’ suggests a sense of family and childhood connectedness that the poet has lost, irretrievably. Like Robert Adamson’s ‘Things Keep Going Out of My Life’, the poem elegises loss through images of house and garden. The second poem points to a sense of distances in a relationship: shoes abandoned on a floor image a transitoriness of connection, a hankering / keening. The third poem gestures towards ‘a deficiency / that does not have a name’ yet it is evident and seems to taunt the poet. The fourth poem asserts ‘the mind’s need / to slip away for a while’ and is a measure of our tenuous connection to the reality of our lives. The final poem’s ‘absence’, ‘failure to attend or appear when expected’, is deemed ‘unauthorised’ and ‘will result in a failing grade’, dramatizing the failure of relationship. Though these poems look crisply formal, their power is in the emotional force of the language.

Aitken’s fifth collection of poems begins and ends (if we take the final poem ‘Rimbaud’s Spider’ as a kind of postscript) with Paris and the Seine – as place, river, ethos and motif, framing a sense of location and identity ‘thrumming with submarine frequencies’. The opening poem ‘Tributaries of the Seine’ has the ‘hypothermic’ poet ‘obsessed’ with measurement and origin, wondering if we are products of geography ‘in the gust of a mistral’s ancient grammar’ or dredged from the ‘mudflats of someone’s youth’. As well, there’s an awareness of the minute ‘vestiges of our heritage … drunk on a minor fifth … in time’s self-immolating hangover’: so the poem opens the collection on an allusive, dense, agnostic note, playfully destabilising the poet / reader’s consciousness and suggesting he/we are subject to subtle local influences which shape our macro-awareness. A bird bath’s ‘blue meniscus fluttering’ suggests that relationships and identity, including parents and their foods and failings shape us and embody limitations that the subject/individual is left to deal with.

In ‘The Foreign Legionnaire’, near the end, the Seine is ‘a limpid green gutter / in which the stars will shine … an absinthe grin’ which allowed poets to ‘[wring] eloquence by the neck … when poems were babies / born in clouds of spoor.’

Geography is an opportunity for Aitken to muse on the associative capacities of centrifugal imagery, so every attempt to explain personality, motive or art in terms of origin, influence or accidental connection, is equally specious. As ‘Nostalgia’, the second poem in the collection implies, acknowledged memories don’t fit the bureaucracy’s determinants: ‘it’s dream-French, not real’. The poet is a ‘drunken swift / nest[ing] in old bell towers’. Identity and history are less a matter of colonialist capitalism or geomorphic shift but more a function of a ‘galaxy map of his head’.

Early on, in the first of Allen’s three epistolary dramatic monologues, the ‘I’ affects diffidence, self-deprecation in the face of poignant moments: ‘I’m sort of on the run but I am not sure what from … I bought a box of Toblerone, telling myself it would be an excellent example of a triangular prism to teach three-dimensional shapes to the kids … before I remembered I am not a teacher anymore.’ The triangular prism becomes a motif for the repeated misprision in self-analysis and relationships: ‘You can only look from one vantage point after all.’ The poem links this to being ‘seated in a theatre in such a way that you get a glimpse of what is happening in the wings.’ But Allen’s ‘I’ wonders if changing perspectives is about advantage or vulnerability, giving us a palpable sense of moments passing.

In ‘Avignon-Paris TGV, Winter 2012’ Aitken writes, ‘Plain speaking is in again. / They say poets can’t do it / but I can, and I will say / that all or part of you (Old Londoner, old plain-speaker) / is all of this, the very scene itself.’ Of course, it’s more complicated than that: the poem positions ‘him’ on the train and conjures images of autumn ‘burning off / when chaff vapourises into rain’ against a ‘palette-key for provincial sunflowers, / lavender and geranium scents.’ It’s a fragmentation of bi-cultural awareness, charged with significance and memory (ghosts of Wordsworth and Coleridge haunting the conversation). Aitken calls it ‘remnant optimism’: ‘a gift / compressed to / miniature, sleight-of-hand, / synecdoche’. His poetry pulls us towards intimacy while remaining grounded in so-called ‘objective reality’. And synecdoche is right, too, as a descriptor of Aitken’s poetry: dazzling – so many parts standing for many more wholes. The poems move constantly from micro to macro; the minute as lens to the world and back again. So the train’s high-speed ‘passing’ and ‘leaving’ embodies separation – cleaving, in both antithetical senses: a ‘French railway after-effect / that radiates the idea of you’.

We see Aitken’s idiosyncratic wit at its most roccoco in ‘Junier’s Cart’, apostrophising the famous Rousseau painting and its apparently unexciting neighbourliness (‘nor lion’s dream of Arabs, / No nude lady of the desert / dreaming of a lion.’) Wondering if ‘it’s a joke on Paris … the irony of a flat tableaux’ [sic]) Aitken sees Rousseau the artist (as we see Aitken the poet) as a ‘malingering taxidermist / who practised on living humans and called it art’: ‘Your eyes in sideways glance / at yourself, the viewer and the viewed’. And then there’s an Australian gaze: ‘others saw it, Nolan’s constable / on a camel’. Aitken is taken by the playful and ambiguous constructedness of the painting – how art and poetry reframe in order to ‘pose’ and ‘arrest’. Later, in ‘Dreaming Rousseau at the Pont Du Gard’, poet and painter are ‘surveying time’s mess’.

Conversely, beneath the pointedly sarcastic surface of Allen’s trenchant ‘eHarmony Quick Questions’ shudders an existential angst, cleverly caught by her juggling of different verbal registers: ‘How important is chemistry to you? / Hyoscine hydrobromide is thought to prevent motion sickness by stopping the messages sent from the vestibular system from reaching an area of the brain called the vomiting centre.’ There is a kind of bipolar fluctuation between intense embrace and almost nihilism running through the poems. The sensuality of ‘Orange Delicious’ when memory of roadside fruit ‘small / and ugly / but so delicious’ leads to a teasing awareness of ‘something / sweeter / more right, more real / just out of reach’. Or, more darkly, in the post-Plath ‘Thirty Minute Meal’ where the family ‘cake’ is metaphorised as a recipe after which ‘[you] put the kids to bed / then put your head in the oven.’ Elsewhere playfully morbid, Allen imagines ‘Emilia Fox slicing me open, / taking out my lungs, weighing my heart’ or herself as a psychiatric ‘Outpatient’: ‘here I’m not mad enough / whereas everywhere else I’m too mad / … / I’ve decided / everyone can come dressed as their favourite / unhelpful thinking style. / … catastrophising, overgeneralisation, / crystal balling’.

Pingback: Review of Archipelago and Liz Allen’s Present – Adam Aitken