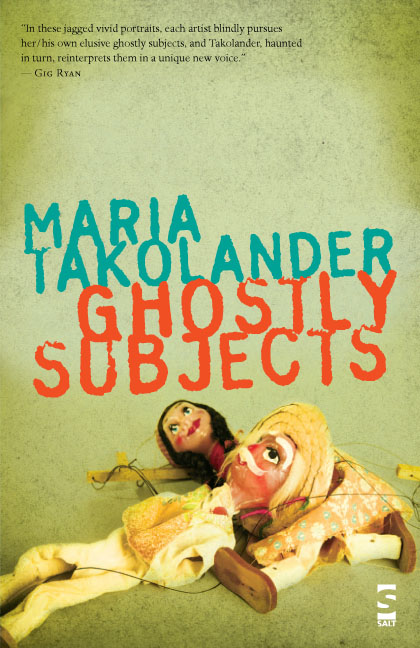

Ghostly Subjects by Maria Takolander

Ghostly Subjects by Maria Takolander

Salt Publishing, 2009

Swallow by Claire Potter

Five Islands Press, 2010

In his 2007 essay ‘Surviving Australian Poetry: The New Lyricism’, David McCooey identified the prevailing mode of poetry in contemporary Australia as a negotiation between experimentalism (the new) and traditional composition (lyricism). This view is apposite in describing the work of many important poets of the last couple of decades; but a number of newer Australian poets have gone beyond and broken with this conciliation. Among these poets are Maria Takolander and Claire Potter, whose startling debut book-length collections can be seen to illustrate what the radical philosopher Alain Badiou has called inaesthetics.

Badiou’s strategy for a philosophical investigation of the arts – and of avant-garde poetry in particular – relies on a belief that art is one of the key conditions for the emergence of universal truths. Accordingly, a poetry capable of hosting such an exigent possibility must negate both the mimetic impulse (to represent/express emotions, images, experiences, etc.) as well as the lyrical demands of conventional prosody such as form and sound, the unity and cohesion of an authorial voice, poetic subject matter, etc. As Elie During has recently written in Alain Badiou: Key Concepts (Acumen, 2010), “Badiou’s underlying poetics is at once anti-mimetic and anti-lyrical. Hermeneutics and aesthetics are thereby rejected in the same stroke.”

The two titles under review perform such a rejection. Takolander’s Ghostly Subjects comes after her 2007 monograph on Magical Realism (Takolander is a lecturer of literary studies at Deakin University) and her 2005 chapbook Narcissism. As such, it may be assumed that her poetry has scholarly, intellectual tendencies, and it should come as no surprise that an entire section of Ghostly Subjects – titled ‘Culture’ – is dedicated to explorations of works of cinema and literature in poems about Stanley Kubrick, Mary Shelley and Sylvia Plath. Insightful as these poems are, they seem somewhat out of place alongside the unsettling and at times confronting pieces found in this powerful book’s earlier sections.

The third poem ‘Euphoria’ sets the tone for the book’s more iconoclastic poems. With baffling and occasionally ungrammatical phrasing such as “Too little and too much” and “I mouthful the earth”, the poem declares its author’s penchant for linguistic playfulness as well as her aversion for the idiomatic. As the collection progresses, these formal quirks evolve into a transgressive poetics that disrupts the formation of an aesthetically coherent voice. In ‘Ghost Story’, for example, the clearly lyrical, Romantic premise suggested by the poem’s first line – “Under a night sky as immense as sleep” – is gradually interrupted and shattered. The poem’s fourth last line is a coarse, abrupt sentence – “A man and woman fight” – preceding an explosion of violence prior to a total negation of the poem’s earlier style and motifs:

Curses settle like asbestos in their word-full souls, then fists, suddenly fleshy as infants, thud-slap.

Reducing everything – all of it – to nothing.

(And so the universe feints, becomes domestic.)

Although the first line of the above passage contains similes, its voice is far more dialectical than lyrical. The “curses” are similar to “asbestos” and the “fists” are “fleshy as infants” only in a new and very specific context, in the “word-full souls” which precede the appearance of the “fists”. Unlike the purely descriptive simile in the poem’s first line (which merely represents the night’s “immensity”), the curses and fists in the poem’s third last line are radically contingent: the poisonous quality – the asbestosness – of the curses depends entirely on a situation – word-fullness – created by these curses, themselves words. The fists are not innately “fleshy as infants” but only “suddenly” become so in the context of the fight between the man and the woman. While the conventional connotation of the poem’s first line takes the “immensity” of sleep for granted, the raw and disruptive phrases that emerge towards the end of the poem are produced as a consequence of a radical break with a pre-existing symbolic order. This rupture in the poem’s internal, thematic unity prompts an annihilation of preconceived notions in the second last line, which in turn brings about the fundamental transformation of “the universe” into a scene of subjectivised, “domestic” violence.

Violence is a recurring theme, as well as something of a structural strategy, in many of the best poems of Takolander’s dark collection. The haunting and somewhat menacing poem ‘Pillow Talk’, for example, does not only include weapons – knives, guns, ammunition – but the arrangement of these signifiers within the poem and individual lines is in itself an act of linguistic terror. The poem’s very first line – “Kindness kills.” – enacts a terse termination of both the meaning of the word “kindness” (something that is most certainly not supposed to “kill”) as well as an incision in the line’s alliterative sound and rhythm. The following lines embody an almost programmatic attack on peaceful associations – mostly to do with sleep – by threatening motifs, e.g. “Inside the bedside drawer / The knife blade”, or “My bed was made. / In the hallway closet, // My father’s rifle leaned.”

By the end of this intense poem, the speaker has become resigned to and/or captured by her fears, and has come to see her nightmares as sweet, desirable things – as “candy”:

There is no rest.

Nights are for unreason.Still I hide the bullets in my mouth,

Mirrored candy,And grind them down.

Bronwyn Lea has aptly described ‘Pillow Talk’ as “a devastating poem in which innuendo lingers like poison.” This acute appreciation of Takolander’s work is, interestingly, part of Lea’s article in Westerly about the highlights of Australian poetry during the 2009-10 period, an article mostly dedicated to work far more conventional than Takolander’s. Receiving recognition in such a context may not have been Takolander’s purpose in writing Ghostly Subjects – as can be seen in, among many others, the fantastically offensive feminist prose poem ‘Prosthetic’ which details the sex life of a modern-day Pygmalion whose sex dolls “had miraculously pushed their hips towards him, receiving his every thrust, their pink-skinned flesh as fleshy as his pink-skinned cock” – yet it is an encouraging fact that Maria Takolander’s daring and subversive work is not being marginalised, and that she has been deemed, by John Kinsella, “a poet who will show us where to look next.”

As for the next title under review, and based on her book’s title and its cover image of a swarm of bumblebees, Claire Potter’s Swallow may initially appear far more lyrical than Ghostly Subjects, and therefore an unlikely title to be reviewed alongside the latter. However, as indicated by the titles of her previous publications – the 2006 chapbook In Front of a Comma and the 2007 chapbook N’ombre – Potter’s work presents itself also as modernist and L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E-like. As such, it may be tempting to see her work as a marriage of the old and the new, and to name her a new lyrist. Yet the poet herself has rejected this nomination and, in my reading, her book conveys a potently anti-mimetic, inaesthetic approach that undermines the core interpretative tenets of conventional lyric poetry.

What distinguishes Potter’s aviary – full of swallows, quails and cranes, as well as associated flora – from pre-existing, nature poetry (such as Ted Hughes’s owls and crows) is that Potter’s birds are fundamentally and at times perplexingly opaque and anti-expressive. They are neither metaphors, nor symbols, nor – despite the poet’s obvious erudition – allusions to other literary birds. Potter’s birds are profoundly ephemeral yet energetic traces of a crucial, unknowable truth; a truth brought to life in language, but never merely represented or shown by language. To state the obvious, Potter’s poetry is, if one must, complex and possibly inaccessible; but it can be more appropriately described as tantalisingly complex and profoundly, unashamedly inaccessible.

We encounter one of the collection’s first birds in the second part of the opening poem, ‘La Haine des Fleur’, in the form of “a stranger who opines neither to stay nor to leave / but squat inside an acorn tree within the gravity / of a feathered cape.” An immediate reading of these lines could see the bird as a humanised entity, capable of “opining” and wearing a “cape”; yet, as the speaker has specified the tree type but has refused to explicate what kind of bird she’s representing, it can be detected that this uncertain “stranger” may not be a representation of a bird after all, despite being a feathery thing sitting in a tree.

In the next poem, an “Asra bird” is invoked to hint at “the heart of the poetic”, a reference to the apocryphal Arabian tribe in the 19th century German poet Heinrich Heine’s ‘Der Asra’. Asra, commonly a Muslim female name, suggests a number of semantic possibilities since the Arabic word’s English transliteration could be referring to three different homonyms meaning fastest, captive, or, in an Islamic context, Mohammed’s supposed nocturnal flight from Mecca to Jerusalem. Either way, the imagistic description of the bird in the second stanza of Potter’s poem (“Half-erased by the sun, a rouge scallop of wing”) is simultaneously enriched and complicated once the avian is named – or perhaps unnamed – as an enigmatic “Asra bird / who dies when it loves” in the third stanza.

Potter’s departure from nature poetry resides in the apparent mysteriousness of her phrases and their indeterminable referents as well as her inversion of the very logic of nature symbolism and allegory. In her richly musical and deceptively lyrical ‘Hollow Amid the Ferns’, instead of symbolic/metaphorical birds expressing the poet’s thoughts and emotions, it is the poet’s thoughts and perceptions that embody bird-like tendencies. In the first stanza, for example, “light cuckoos into your ear / pours a canticle / of warm wind”. The metamorphosis of electromagnetic radiation into something that “cuckoos” and produces “warm wind” is not a finite process; soon the birds that have emerged out of the sense of sight are distinguished from and contradicted by new, inexplicable birds that have an internal, personalised provenance divorced from external reality:

through the bracken egress

there’s a crowbar for the mudflats

which sings better, takes

longer, provides less resistance

than my hoarse swallows

The seamless linguistic transformation of “crowbar” from a mundane object to something that “sings” is not a Romantic, imaginative gesture, but a critical citation of the origin of the word “crowbar” – the bird crow – which disrupts the description of the visible in the first two lines of the above passage with the introduction of an invisible, inconceivable entity in the following two lines – a crowbar that sings, etc. The speaker is not, however, content with this disruption producing an absurdist, surreal image, and she negates such a possibility by undermining the potential absurdity, even comedy (of a singing crowbar) by contrasting the subject with deeper, more solemn and more mysterious birds, the speaker’s own “hoarse swallows”.

The same strategy is deployed in this intricate poem’s next stanza in which the rather prosaic, realistic discourse of the stanza’s first two lines is ruptured as a consequence of a subtle yet irreversible shift from the literal/observational to the subjective and unfathomable:

there’s a wash-shed with nettles

converted for quails and their speckled eggs

which provides better shelter

than the pucker of my white breaststhrough the bracken egress

my dreams slope along fiendishly

dragging a train of red silk flowers

and spitting rice

Although I have been aware of Potter’s work for some time, it was upon reading this poem in an issue of Meanjin last year that I came to anticipate the release of her debut book-length collection. My expectations have been met and exceeded partly because of the consistently sophisticated and exquisitely crafted pieces found in Swallow – another highlight being ‘Ladies of the Canon’ in which a subtle variation in enjambment in the repetition of the first stanza’s closing line at the end of the poem (shifting emphasis, in my italics, from the sentence’s first verb in “a bird might cheat / and drink its music from the canon” to its subject in “a bird / might cheat and drink its music from the canon”) envelopes a feminist revision of the artist-muse relationship. Furthermore, I am particularly pleased with how this poet, obviously capable of writing aesthetically accomplished poetry about birds and other nature signifiers, has instead produced poems that resist and obstruct interpretation and confidently refuse to accommodate less curious readers’ demand for accessibility.

Viewed together as examples of recent debut collections by truly outstanding younger Australian poets, Ghostly Subjects and Swallow challenge the late Peter Porter’s observation (as quoted in the introduction to Best Australian Poems 2010) that the country’s poetic avant-garde is “dispersing”. Furthermore, it is hoped that books like these will also do away with the very dubious perception of Australia’s younger female poets as writers of aesthetically refined yet unadventurous poetry – e.g. “Ladies of the Lyric”, a rather irritating phrase used during a recent online forum, as cited by Lea in her Westerly article. These two exceptional books demonstrate the sheer boldness, originality and complexity of the poetics of two anti-lyric female poets.