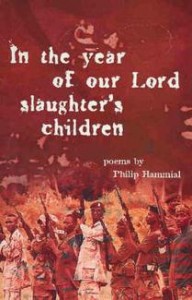

In the Year of Our Lord Slaughter's Children by Phil Hammial

In the Year of Our Lord Slaughter's Children by Phil Hammial

Island Press Co-operative, 2004

Who is Philip Hammial? If you read Hammial's 16th book of poems, it will strike you as surprisingly biographical without sounding too auto-biographical – after all it's Philip Hammial poetry. Who is Philip Hammial, the poet? What's his world?

Is he the hippie tourist on page 12 paying homage to Siva's lingham in Armanath? This lingham's in all his books, I believe. He keeps going back to that frozen phallus, that tower of ice. It's definitely something to do with his Kharma. Or is Hammial the traveler/poet in Ghana, enjoying Mama Dosa 'writhing in a trance-/ about to be ridden, bareback, by one of the local gods'? (I haven't met Mama Dosa before.)

Hammial is also the US sailor, who, in 1958 found himself queuing up for Navy strength penicillin, then on a night on the town fingered by forty hands in a Cuban boudoir. And there's Hammial the teenage delinquent, this time in Norfolk (Nofuck) Virginia being beaten to a pulp by a bouncer:

Philip of Detroit / as conniveur in the Age of Song and Dance

the backdoor man slipping out

in the Age of the would be Poet Laureate.

There's Phil the car assembly line worker in Detroit struggling to keep his limbs intact on a line 'more unstoppable than the Balkan Wars'.

Who is the real Hammial? Certainly not the authenticly insane, but the friend and mentor of those who are, and whose art keeps true madness from destroying them. The poet Hammial is also the bete noir of those devils whose madness and mad visions he writes about so compellingly, who's anti-lives consist in the recruitment of armies of young boys drugged into a frenzy of killing.

Where are angels in all of this – safely but sadly bottled in formalin.

Mad Phil is the married man who finds himself and his new wife in a Chicago brothel, on their honeymoon, kept awake all night by grunting men, slamming doors and the squeals of fake orgasms? Philip Hammial lived Blade Runner before the movie was ever made.

And what is a Philip Hammial poem?

Certainly more than 'wordplay', certainly more than 'an interior monologue with its backlog of sordid realities to sort out', more than 'painted faces of no significance'. Certainly more than 'semantically disturbed phrases'.

More than 'a swamp where the insolvency of imagery / has reached epidemic proportions', a line in a one of Hammial's missiles aimed at Australian Poetry?

This book, In the Year of Our Lord's Slaughter answers these questions in a way that's new in Hammial's work: if there's always been violence in his poetry, then this volume answers violence with more than violence – with linguistic panache with regret, certainly, with anger, with a passion for protest than never tilts over into despair or sentimental self regard. This is the power one finds in the visual Apocalypse of painters like Bosch, (it's no accident that sea-going vessels figure so often: a book conceived as a ship of fools, Captain Hammial at the wheel, in full technical control of the machine, 99% of the time.)

Hammial's poems ride the sonic waves that still radiate from the impact of Expressionist art, the art Hitler most despised, which the fascists labeled 'decadent art' because it refused to ignore the perverse and perverted. This was art that could hold a mirror up to the erotomania and fetishism of Hitler's and any other megalamanic's own war machine. It is a satiric style that strips the fascists of their gloss. This book invokes a world where the Commandant and a whole Schloss of pissed brownshirts vomits on their own uniforms. This is burlesque and a passion play for devils where real people get killed, tortured, raped.

Heavy stuff, for sure, but perhaps this is the sort of poetry to stop us feeling relaxed and comfortable in Howard's Australia – and Howard also goes through the mill that is this book. So I don't think Howard would endorse it.

I think this is a book of poems that never rests, that does not claim another world that transcends the waste of this world. Nor do I think this is an unhappy book or one that is resigned or resigns its function: as a kind of repository of sympathetic magic, of soothsaying magic. In one poem, Hammial speaks direct to his long dead mother, like a conversationalist Shaman Hammial absorbs the negative energies and turns it to what? A spectacle, a ghost train ride, but a hundred times better.

It's better than aspirin, ecstasy, or dope. It's a book that harnesses the great power of the satirizing crowd, the mob, the people or the proletariat – at the same time it a book that knows that the very same mob can kill. Still, this is a book of voodoo incantations without the grandiose tone of the Beats. This is collection to be read on the 430 on your way to work, I guess. Who knows? In a poem about writing poems that embody the life of the body, Hammial writes it's 'the thrill of swim or sink'.

Adam Aitken's poetry has been featured in several recent issues of Cordite.