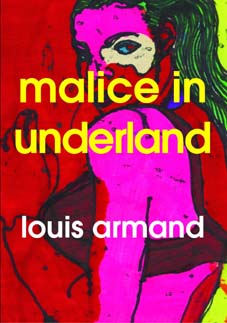

malice in underland by Louis Armand

malice in underland by Louis Armand

Textbase, 2003

The title of this book is an early manifestation of its endless intertextual referencing, as well as one example of the author's restrained penchant for relatively silly puns. It is also an understatement of the viciousness of some of this poetry. And, although the titles of these poems are packed with references to other elements of culture, particularly obscure ones – there are several, such as 'washington crossing the delaware', that derive their title from a painting – the connection between title and piece is connotative rather than denotative.

The book opens with the title piece, and the first stanza seems pointedly to indicate the sort of hell the reader is going to be led through by this book's 'story of contrition':

to begin with injustice is inseparable from life – smeared

with the blood of old movies we hoped to outlive.

how effete your singing voice is – the mannequin

in the front window who is she?

candour you say is the best policy a trained

parrot to tell the story of contrition its

one good eye spastic with sleep

This is followed later in the poem with mention of 'hunched shadows/ of the end-of-the-world coming towards us' and concluding with:

huge grapeblack clouds in harvest

waiting to burst. this place you say is a bloody place

This poem is hardly a friendly invitation to partake of a relaxing read.

Armand is very much interested in the contemporary, and in this book he presents his reader with a bruising entourage of scenes, images and juxtapositions wrenched from combinations of everyday urban life and ideas bred and fattened in Art. He regularly abandons punctuation, syntax and (often irritatingly) pronouns, prepositions and subjects – though there are plenty of objects – in the course of his poetry, a set of practices that ensure the reader feels more than a little lost, abandoned perhaps, amongst wave after wave of dismembered images and disjointed events that roll by. Armand makes some acknowledgement of these difficulties he is inviting his reader into at different points in the book, most directly in 'side b. allegorical procedures' where he states '”free association,” for/ example, is no more natural than/ cutting up.' It is statements like these that emphasise an ongoing atmosphere akin to 'abandon all hope?' – where you are located whilst reading this book is 'no more natural', 'unnatural' even, and if you want to survive, it becomes necessary to surrender your understanding of what should come next and start observing what is in fact coming at you.

His aversion to uppercase and traditional punctuation confounds smooth reading: the text appears at first glance to flow like a stream across the page; but to read it so quickly and effortlessly as this suggests simply bamboozles the reader with a wash of disintegrating images that quickly deteriorate into a slurry of words and phrases, cliché even, that hold onto nothing. Only with care and a considered pace can sense be made of what is happening, and there is definite sense (in some sense) to be made. One of the key effects of all the dislocation and interruption in the earlier pieces is to induce a reading of more straightforward narratives like ‘sonnabend' or 'border pastoral' as though they too were cut-ups; and in them the natural disjunction of more traditional syntax is highlighted. Armand induces an inability to treat anything as concrete/straight forward anymore.

The materials used to build these poems might be public property, but the majority of the poems seem intent on the personal, either emotionally or physically – recollections of parties attended, days spent roaming cities, personal relationships – and the various cultural referents are at least as much for the author's benefit as the reader's. 'Euclid', for example, presents the intentional and incidental geometries of an urban landscape, allowing the flow of lines to guide the narrative of the poem. Yet the earlier casual mention in 'Split Screen with Static' – a poem that could be read as the reconstituting of a private residence and its neighbourhood by way of fragmented recollections – of 'getting off at euclid avenue' is one of many indications as to how thoroughly multiplied and intertextual (as well as extra-textual) the meanings to be made from this book can be.

When these poems are not garishly carnival they are bleak and awful. Though it is often difficult to identify a single focus or point to most of these poems, they inexorably, implacably thrive with life whilst smothering the reader with sensations of continual decay – decay of the very reading process – a kind of literary carrion. This is not to say that these poems are not engaging or exciting – William Burroughs' Naked Lunch, for example, can be revolting at times, but is still a great book. And though this book may not necessarily be 'great', it is stimulating and absorbing, once you learn how to cope with reading it. Side by side with pieces of city streets, commercial establishments, social interactions and migraines, or rather, as a process of relating these things, the manipulation of the language continually pushes the reader away from any sense of security, any sense of confidence at understanding what is happening or about to happen. Again, it is most often only via some understanding of the various cultural codifications that a grip is to be maintained on this disturbing reality.

When first faced with the saturating degree of obscure references and willful difficulty these texts embrace, it is tempting to dismiss the author as unnecessarily pretentious and to declare that an audience who delights in this comprise: (A) those who think anything difficult, vague or pointless is 'avant garde', and are therefore only disappointed by art they can understand; (B) people who assume someone else knows what it means, therefore they themselves are deficient for failing to do so; (C) the author himself; (D) the author's close associates to whom he may be able to explain the point of some elements in person (and outside the text).

But that would be selling all this hard work short.

Of course, pretentiousness is not of itself a bad thing. Of all the contrivances in this book, one of the more (if not the most) interesting is 'king and queen surrounded by swift nudes (duchamp tartakower paris 1930)'. This transcription of a chess game is intriguing. Like Reuben Keehan's eponymous exhibition in Chippendale that featured a wall and a half of black and white image-less reproductions of the covers of the Situationist Internationale, this poem does something very visual whilst resolutely declaring itself to be textual, and remaining so. The reader/viewer is caught looking for the changes, the nuance that breaks the cycle of 'pawn to queen's knight four queen to queen's knight four queen takes queen?' and so on. Whilst most of Armand's poems appear surreal and disjointed specifically because of his manipulation of the text, though the subject matter could loosely be regarded as of the 'every day', 'king and queen' is a poem that is an unmolested transcript of a simple event with which Armand has not interfered except by way of line breaks, yet it looks and reads like a work of extreme absurdity. That is its beauty. This poem is baffling in its simplicity and integrity, and it has an immense appeal set here amongst the disjunction of this book: amongst all the waves of dislocated narratives and endlessly deferred referents, here is a piece that looks like it can be understood, and contained.

Without the subtitle, Armand is inviting the readers to engage with the piece at will, work at it, interpret it however they want. This poem has a great excitement about it; in a book of poems that readily walk away from accepted conventions and seem to seek their own rules of engagement, this poem has the greatest integrity of internal logic of any of them; it is airtight in its functions and could not be otherwise. The observer feels locked out by a wall of glass: the machinations are there for all to see, but what this piece actually is cannot be determined. Anything from an allegory to an account of a game played by the author himself is entirely feasible, and its purpose too is obscure even as it is right in our face: there are so few referents here, so little that analysis can be applied to; simple motions of a closed system, a single game of chess, plus the somehow beautifully majestic title 'king and queen surrounded by swift nudes'. What could frustrate but instead inspires is that this is an actual, unaltered ready-made, a found object the artist can present but has no need to modify; it is something that works in the world outside art. It is something absurd and bizarre that is also a direct, realistic piece. 'king and queen' should strike the reader as devoid of emotion – deadpan relay of information – yet it has an irresistible humour that culminates in the final one-word line, simultaneously exploding and deflating with 'resigns'.

And then he goes and spoils it all by saying something stupid like 'duchamp tartakower paris 1930'. This subtitle sticks like a splinter in the 'less educated' reader's eye. Something is missing in your engagement if you do not know what this subtitle refers to – that's one possible understanding to be taken from the subtitle. No longer allowed to pursue understandings of the poem across the breadth of all possibilities, the reader and poem are reined in, or pushed away. If you do not find out what the subtitle means, you are forever missing a piece of this puzzle. If you find out, you may have to exclude any number of beauteous objects that no longer fit. In this interpretation, the subtitle does not enhance the poem, it excludes the reader. It congratulates the 'erudite', as they term themselves, contriving an in-joke that has no value of itself but only in its function as a means of exclusion. Of course, those out there more familiar with Duchamp's work will have realised that brilliant title, 'King and Queen surrounded by Swift Nudes' is taken from a 1912 painting of Duchamp's. Though this superficially seems relevant, in reality it is not: those who know of the painting more than likely would associate it with Duchamp without the inclusion of his name. Those unfamiliar with the painting do not require pointers like the subtitle to decode the poem – as stated above, it is a far more beautiful work without the explanatory/exclusionary subtitle.

A more generous and necessarily more educated reading of the poem would acknowledge the unfairness of deciding that this is definitely what Armand is trying to do with his subtitle. The possibilities again are numerous, but he is obviously not so much interested in engaging with the incidental object as with the artist who happens to have an association with it. By writing a poem based on a game of chess played by Duchamp and Tartakower, Armand moves over the interesting ideas that emerge from a poem built on a game of chess and instead engages with notions such as Duchamp's claim that 'chess is much purer than art in its social position'. He is engaging with the image of Duchamp as artist and chess player, as a brilliant mind held by some to possess genius. He is also making fun of Duchamp's creative practices that in turn made fun of the artistic establishment with his use of ready-mades and the like.

The poet is never at rest in the workings of these poems. What quiet moments there are seethe with the tensions that surround them, and the reader is likewise kept on edge by way of nothing so much as the disorienting and distressing contusions of language and image. Amongst this confusion some entertaining similes emerge, occasionally even delicate and tender such as, in 'ostinato', ‘the meaning of discard/ a crab without a shell'. And there's something (dare I say) 'punk' about the musicality of this poetry: at first read abrasively dischordant and apparently lacking music, it quickly reveals itself to be not only brutal, broken and unrelenting in a thoroughly modern way, but also very melodic – like much of the narrative and the individual images in this book, the musicality unexpectedly coalesces out of the chaos, as in the last two lines of ‘ostinato':

crates packed with offcuts waste product effluvia which also are the

facts of life

As well as incorporating a swathe of cultural references and at times engaging with their particular ideas, as well as repeatedly presenting an inhuman, detached collage of contemporary urban places and events, these poems are also often intimate and personal, simultaneous to their broader foci. And, their surface being mutilated with the willful interruptions of that collage, the personal is allowed to exist semi-submerged, therefore less alienating to the general audience for whom these personal intimations might otherwise be embarrassing, boring or trite.

One annoying feature of this book that no doubt many would feel to be minor or irrelevant is the first statement in Armand's biographical note at the back: “louis armand [sic] is an artist and writer”. Though in certain circumstances this distinction need not be the separation of two acts but rather two ways of approaching the same act, it is clear that in this particular case the former is exactly what Armand is getting at. In other words, this note declares Armand to be an 'artist' for his endeavours in visual media (he is a successfully exhibited painter and drawer), the 'natural', unstated conclusion therefore being that a 'writer' is Not-an-Artist. This is one presumption borne of pure piggish smarm that malice in underland and Armand himself are most unfortunate to have associated themselves with, and begs the question, why shouldn't this book's difficultness be disregarded as exclusionary and self-aggrandising?

Michael Aiken writes for the literary-critical site www.texture.cc and will be guest Features Editor for one of texture's mid-2005 releases.