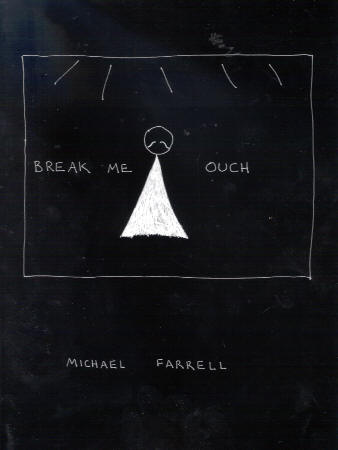

Break Me Ouch by Michael Farrell

Break Me Ouch by Michael Farrell

3deep Publishing, 2006

I've been puzzled by Michael Farrell's poetry for a long time. Sometimes I think I get it; but his writing is mercurial, and for every one of his poems that I've understood or enjoyed, there's another that leaves me cold or just confuses me. It's impossible to decide whether Farrell is doing something incredibly formal and intellectual that I'm not smart enough to understand, or whether he's tricking his reader into thinking that there's something deeper taking place when he's in fact only mucking around and playing crazy games with language.

This question isn't really answered by Farrell's latest collection, Break Me Ouch, but there is undoubtedly something more accessible about this amalgamation of deft-yet-arcane poetry with comics illustration. The poems themselves vary; 'Death to Fine' is, for example, abstract:

tho I don't &

this isn't wear ties

to fill a paper

caboose can u see

the tautology oh jeeze

'Star', on the other hand, is clearly more straightforward:

you're in highschool

lost a leg

in iraq now

you play rugby

in the paralympics

you're a star

And then there are pieces that verge on the obscure, such as 'walk on pieces':

you walk by and die

all that ive left poolish

the tv the mice watch

im just your broken friend

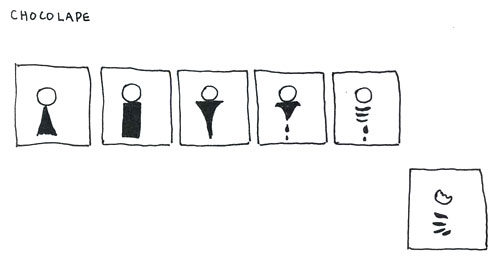

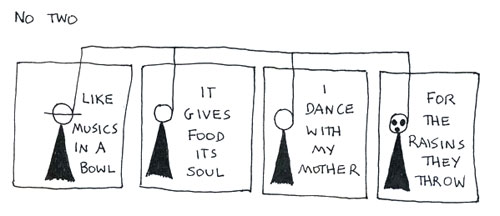

Each poem (none longer than fifty or sixty words) is broken into segments that are bound by a square border and accompanied by a kind of narrator object that is drawn as a simplified circle-and-triangle humanoid, with variations as dictated by the poem's text. As the book progresses these transformations come to resemble a kind of metamorphic dance.

The hand-drawn, hand-written artwork is beguilingly cute, both complimenting the abstract nature of the poems and undercutting their opacity. As comics theorist Scott McCloud proposed in Understanding Comics, the more simplified a drawing of a person, the more able a reader is to identify with it. In this respect, Farrell's choice to use such iconic illustrations works well in terms of drawing the reader in (no pun intended).

So what is it exactly that makes Break Me Ouch a comic book as well as a poetry collection? Is it enough to put boxes around the words and add pictures? Does that make something a comic?

In the crudest sense, perhaps, the answer is yes, but the language of comics is a sophisticated one that is capable of much more than simply showing what's been told. When Farrell's narrator sprouts spines as he talks of dragons, grows a beard when he mentions beards, sprouts roots when talking about trees, changes the shape of his head into a heart when citing love, and wears a bouffant mullet when name-dropping Aussie '80s band Wa Wa Nee, these comics are only scraping the surface of the potential within the language that is available to them. Comics is an artform that uses text and image in combination, and it is a much more satisfying comic that combines text and image in a way that complements rather than straightforwardly imitates.

There are examples of less literal visual accompaniments to the text – especially the 'silent' poems that are all illustration and no text bar the title. These works are the ones that best explore the use that can be made of the visual communication made possible by the narrative progression of images that is integral to good comics art.

The works that combine illustration and text, however, while amusing, tend to make Farrell out to be an experimentalist who has only been attracted to an art form outside their usual practise, and is yet to move beyond mere fascination and master the capacity of that art form.

Nevertheless, Break Me Ouch is an interesting addition to Farrell's bibliography, more evidence of his interest in exploring the range and capacity of language. It will be interesting to see if Farrell continues this particular experiment and whether he comes to produce a more sophisticated kind comic/poetry hybrid in the future.