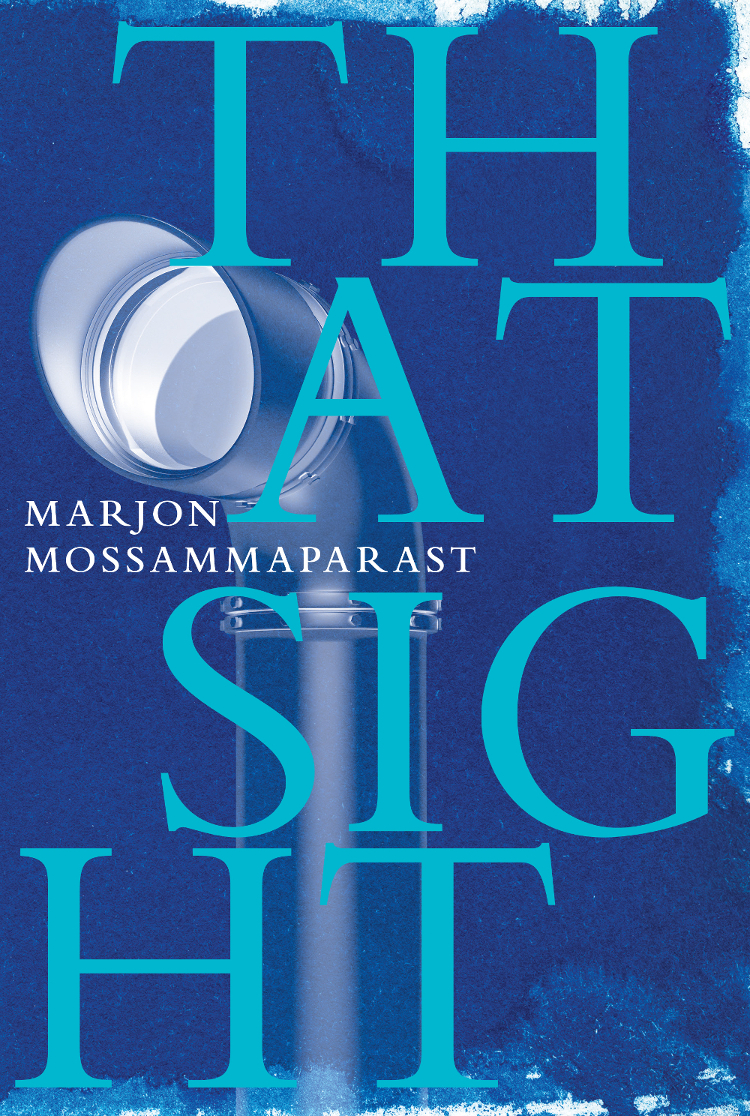

Photo by Gen Ackland.

Marjon Mossammaparast’s That Sight offers us a wide-ranging series of viewpoints, taking the reader through various locations and histories. It zooms out to cosmological heights, and even beyond to God (or the absence of God). However, this ‘infinite range’ is joined by exquisite detail. A grandmother’s memories of her ‘brood’ become ‘a creeping diaspora spreading from one heart / in a lengthy queue of continents’. A rock star’s face is ‘a pallid moon straining / with carrying all that light’. Mossammaparast’s images are always grounded and assured, even as they reach out into areas that seem to exist beyond the limits of language.

That Sight folds disparate locations together. In ‘The Call’ a superannuated figure in the Australian suburbs receives visions of Lake Baikal, Omsk, and Ishqabad. Elsewhere, in ‘Study for Two Hands’, Macau is set down alongside Lisbon and Warrnambool as though these places might be naturally aligned, perhaps along the creases of a folded world map. Indeed, the book offers a vast and compelling psycho-poetic geography, something far richer than any of those overworked terms – transnational, diasporic, cosmopolitan – we often deploy in our quest to describe the possibilities and exigencies of global space. Mossammaparast’s poetry pirouettes from Zhengzhou to Balwyn, Sydney to Syria, Kowloon to Buttermere, Mecca to Paris, with its eyes on both oceanic depths and planetary heights.

And yet these loops are not just geographical wanderings; they are also loops in time. Mossammaparast offers a series of beginnings and endings. The biblical book of Genesis threads its way through the volume with its injunctions to ‘be fruitful’ and multiply, and its mythic reach that always seems perspectivally displaced. At the other end of history, we are warned about the various iterations of the apocalypse: the ecological tipping points of ‘Fashioner’; the double-edged ‘Judgement Day’ of Paris after a terrorist attack. These versions of the end are fascinating and terrifying both in their implications and in their devastating, telegraphed slowness.

Mossammaparast gives us a collection in which God continually approaches and recedes. The opening poem is titled ‘Lapsed Believer’. In it God is taken apart ‘like an artform’. But ‘still He rises’. This dialectic between belief and unbelief can be intuited in the scraps of liturgy that peer through the poetry; God’s incarnation as a sweaty Nick Cave; the allusions to the Qur’an; and the thrum of the ‘I ams’ that surface and resurface throughout the volume. These ‘I ams’ alert us to the name or non-name of God (cf Exodus 3, John 8). But they also reflect the poet’s deep interrogation of human subjectivity, a desire to discover some kind of consonance between the immanent and the transcendent within the elegant fragility of the human body. The collection’s ‘I ams’ can be thought of as homophonic echoes of the iambs that have an important role as key building blocks within the Western poetic tradition. That Sight is open to the relationship between ontology and rhythmic patterning.

This collection shows an attentiveness to language, to its playful surfaces, the intractability of its hidden grammars, its restless translations and transpositions. Yet there is always a sense that beneath each poetic scherzo the ground could give way and expose everything to the abyss. Therefore, Mossammaparast’s poems aren’t merely vehicles for clever linguistic exhibitionism; rather, they are always aware of ‘the weight of language’, its possibilities and consequences. As a result, That Sight explores a series of conflations and paradoxes, where the outside is in the inside, the universe is in the body, and the ‘beginning is in the end, the atom in the sun’.

Cover design by Zoë Sadokierski