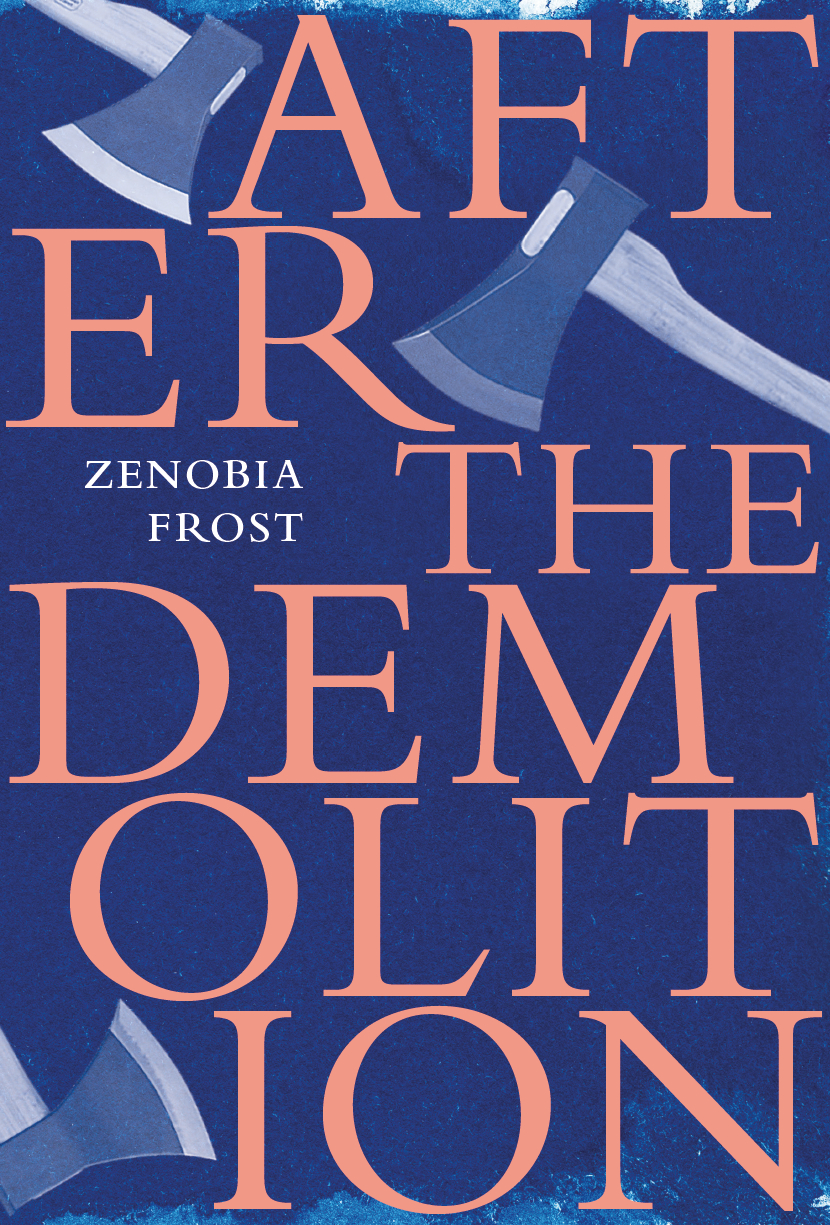

Philosophical questions of reality and duality underpin many of the poems in Zenobia Frost’s After the Demolition, leading to a sense of rebuilding and remembrance in the aftermath of abodes. The potency of houses is a recurring motif in Brisbane literature, from David Malouf’s 12 Edmonstone Street and the imprimatur left by old Queenslanders on the psyche, through to the grotty hostel of Andrew McGahan’s Praise – an olfactory affinity clear with Frost’s generation too: ‘the corpse of a sofa / its antique smell of bong water’.

In the book’s first section, ‘Schrödinger’s Roommate’ (alive and dead at the same time?), the question of reality is tied to the rose ceremony on The Bachelorette, with a nod to Gertrude Stein. The cheesy on-screen dialogue is juxtaposed with sexual tension off screen: ‘She’s come around to watch – is this a date?’ and thus the show’s hyper-hetero normativity is queered in situ while watching Sophie Monk: ‘The bachies pile coats on Soph, till all we see / is bubbly flute and Uggs. You’re probably warm enough, / so I won’t offer.’

If Andrew McGahan was the masculine antihero of nineties Brisbane grunge, Frost interjects female corporeality into the ever scarce rental market – ‘Furrows to hang a final pendant light / from my cervix – as she invokes the transitory nature of domesticity, as well as a deeper aesthetic sense of time, liminality and decay (or poetics of space) among the mildew and mismatched dishes.

Along with reality TV come the neighbours wanting to Airbnb your spare room for their relatives. Though for Frost, it’s not the McMansioned Queenslanders, but the abandoned houses slated for demolition, the fixer-uppers and the ‘left chunk of a heritage house’ that instil a genealogy of the recent past: ‘a map on the wall from 1995 / shows all the Brisbane I have lived since’. She holds on to glimpses and details, blueprints and ‘Distractions at Rental Inspections’, like the tenant with ‘distended nipples’, and lets sensuality inhabit the gap between real estate rhetoric and reality.

Frost’s poetic is a kind of antipodean neo-Gothic in ‘fungal lace / the Hills Hoist a skeletal rotunda / where bats dry out like lingerie’.

The book’s second section, ‘The Loneliness Act’, continues the witchy tone. The poems read like bloodstained parables and speak obliquely of family grief and loss, including the death of Frost’s father. These poems engage the duality of life and death and the unheimlich of bodies as vessels.

The third section, ‘Stations and a Crossing’, is an oneiric poem about travel in an unnamed city, a male lover who ‘leads you to a room you’ve never seen. An aquarium. You’re so tired of water./ In the tank, women float like weeds.’ Then, reminiscent of Robert Browning’s ‘My Last Duchess’, “These / my former loves / fingertips’ / on glass”. Relationships and infidelities in the #metoo era are a theme of the next section, ‘Cursive Fever’. The terrain expands across travel in America, ending with a love poem, ‘Bathers’, which reconstitutes agency and desire for women in water, and the illustrious image reportoire that precedes them.

After the Demolition begins by articulating the various insecurities underpinning the issue of housing for the millennial generation and expands this into a quirky, queer, feminist alter-poetic for living and dwelling.