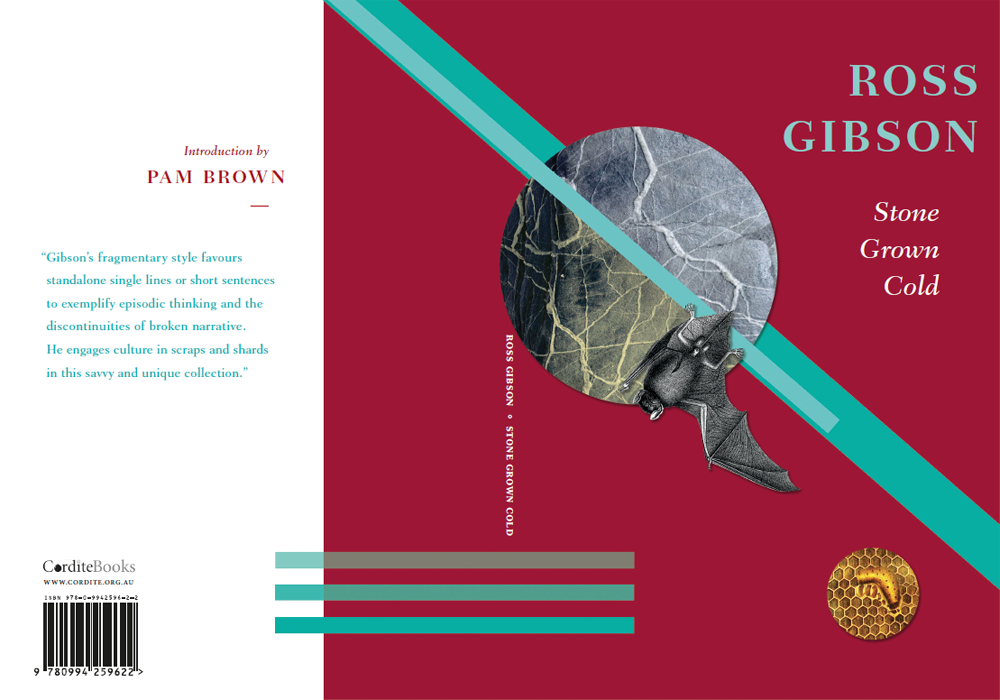

Cover design by Zoë Sadokierski

The works that Ross Gibson has written and edited over the past thirty years could be classed as political aesthetics. In books like Seven Versions of an Australian Badland, chronicling the wretched historical miscreants of Queensland’s Brigalow country, or 26 Views of the Starburst World: William Dawes at Sydney Cove 1788–1791, speculatively tracing English astronomer William Dawes’s scientific work and his relationship with the Indigenous Eora people of Sydney Harbour in a few late years of the eighteenth century, Ross Gibson’s method is procedural. Seven Versions and 26 Views form a compositional design that he has described as ‘fractal’, allowing unfixed multiple views and patterns. The author’s practice of creative fragmentation, applied to the poems and short prose pieces in this new collection, eschews linearity and dull chronology.

The epigraph from modernist North American poet William Carlos Williams presents a complex and strange concept of redemption linking the ghosts of genocide with authenticity. The stanza works to feature a universal Western historical quandary. Ross Gibson’s fascination with history is reflected in the quote, and often his sombre choice of language forges a kind of early modern trait that informs particular effect or mood throughout this book. For example: using a rare word like ‘stochastic’ when he could have said ‘random’, or writing ‘prodigious’ instead of ‘huge’ to describe some fruit bats flying over the inner Sydney suburb of Redfern. I think, in the author’s lexicon, ‘random’ and ‘huge’ would have sounded too mingy.

In the preface Gibson tells us that everything here takes place in a chimerical town that we, the readers, ‘know well’. The first poem is a short, notational, prosaic piece that riffs on twentieth-century Sydney poet Kenneth Slessor’s well-known World War II poem ‘Five Bells’, as a minimalist remix of anthropomorphised tugboats, mists and pile lights. In spite of the minimalism the intent is serious and leads directly to a 2014 hostage incident in a chocolate cafe in ‘Martin Place’, one that Sydneysiders now call ‘the siege’. There is topicality here but it’s agreeably unpredictable. Gibson’s fragmentary style favours standalone single lines or short sentences to exemplify episodic thinking and the discontinuities of broken narrative. He engages culture in scraps and shards.

The performative and visual are prominent in Stone Grown Cold. Gibson is also a filmmaker and creator of audiovisual installations. Sometimes his poetry can be imagined as film, sometimes as song. His lyrical adverbial phrases enhance narrative possibilities that relish the abject, the perturbingly awkward and the disaffected, sometimes in archetypical ordinary suburbs like Rooty Hill – ‘The street’s a tract of sump-oil’ – and Miranda Fair – ‘Go set a suburb on fire.’ In one deliberately unmannered poem everyone is so far off their faces on ‘meth home-cook’ that they have become embodied spectres whose ‘thoughts waft all misshapen.’ Other situations or scenes have haunting eerie undertones that are deliciously creepy – ‘They brought a cold mattock up from the basement’.

Not everything is gloomy though. There’s plenty of genial humour and wit in the sets of Zen-ish lists of tasks and personal superstitions, in an experimental rendition of pop songs like Russell Morris’s seventies classic ‘The Real Thing’ and in some celebratory sinning – ‘Sex in a church. Minutes later: a hailstorm.’ As a bonus, Gibson gives seasoned advice to the bewildered – ‘Bluff your befuddlement with droll savoir-faire.’ These are some of the many unusual pleasures to be found in this savvy and unique collection.