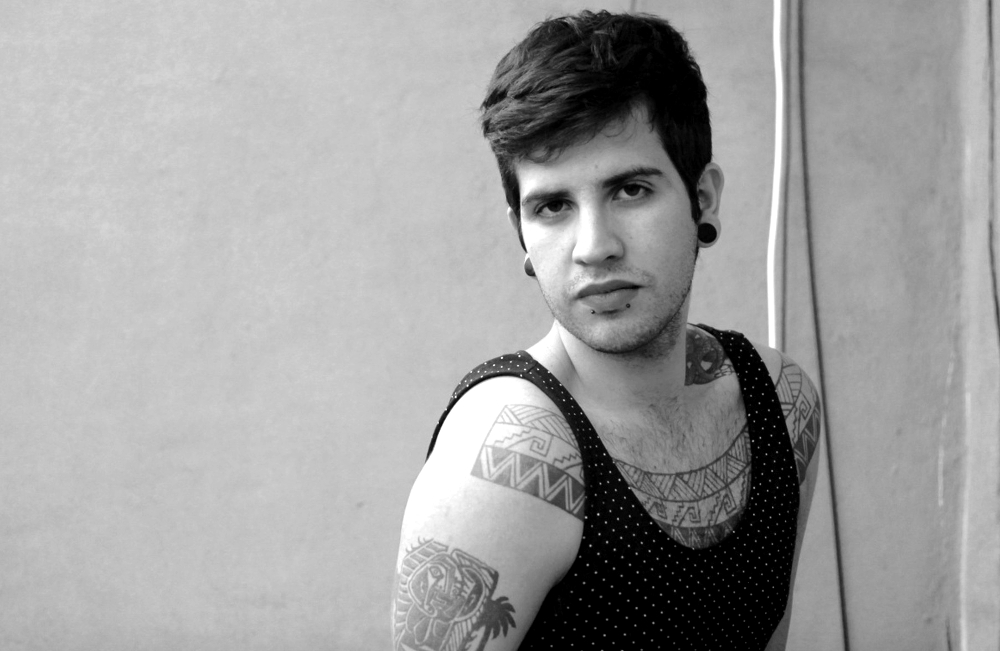

Image courtesy of Jess X Chen

Christopher Soto (aka Loma) is a Brooklyn-based poet who has received several awards for his writing and activism. Most notably, he is the author of the chapbook Sad Girl Poems, which discusses his experiences with domestic violence and queer youth homelessness. Born in Los Angeles, Soto relocated to pursue and receive an MFA from New York Univeristy. Since, he’s had a pronounced effect on the literary world. He is the editor of Nepantla: A Journal Dedicated to Queer Poets of Color, founded at the Lambda Literary Foundation and will be published by Nightboat Books in 2018. He is also the cofounder of the Undocupoets Campaign, working to create grants for undocumented writers in the United States. I corresponded with Soto before he began his most recent tour, discussing his life and work in literary activism and what it is to be a poet in the incipient days of the Trump presidency.

Ainslie Templeton: Thanks for taking the time to talk with us, Loma. I saw that you were recently nominated for the ‘Freedom Plow Award for Poetry and Activism’. Congratulations. Can you tell us about the future of literary activism for you?

Christopher Soto: Thank you. I’m excited about that nomination, to be alongside Francisco Aragon and J P Howard who are friends of mine (and Andrea Assaf whose work I am just discovering now). There are so many people doing literary activist work so it feels special to be recognised.

As for the next steps I want to take within my literary and activist explorations; I want to finish my first full-length manuscript and finish editing the Nepantla anthology with Nightboat Books. Other small projects, such as the Trump Tower protest I hosted, will likely come along the way.

AT: Can you tell us more about the Trump Tower protest?

CS: Yes, I worked with Kyle Dacuyan and Brittany Michelle Dennison to host a ‘Poets Vigil for the NEA’ outside of Trump Tower. People gathered to mourn the proposed loss of the National Endowment for the Arts, to read poems and to yell at Trump. The NEA’s annual budget is approximately $150 million (or below $0.50 per person annually). The proposed defunding of the arts is not about saving a budget but rather it is about stifling the creative and intellectual communities in America.

AT: Did your literary activist endeavours start with you first chapbook Sad Girl Poems? I know that you brought this chapbook on a ‘National Tour To End Queer Youth Homelessness’, can you tell us about that?

CS: I’ve been protesting for over a decade now. My first day of high school I ditched sixth period to go protest President Bush and the wars in the Middle East, when he came to speak in my hometown. Also, in those days I would host large poetry events as fundraisers for various causes. I would bring in poets, rappers, drumline, breakdancers, everyone would come together in their arts for a particular cause. In high school, I was speaking about Darfur. Now, my politics have continued to grow and shift and the projects that I am organising are even more developed. One such project is the ‘National Tour to End Queer Youth Homelessness’, which I started after my chapbook launch. That started in part because I was on the verge of homelessness again myself at that time.

AT: I was really taken by your poem ‘Transactional Sex with Satan’, and found myself rereading it a few times. In it you write:

Bound & bruised // I’ve become the siren & shipwreck // synonyms for lonely. My sex is // melancholic terrorism // or // witchcraft in // the Catholic Church.

What’s your relationship with the confessional (poem) and how that relates to innocence?

CS: Rachel Zucker was my professor and taught me about contemporary American confessional poetry. Yet, I still have a hard time understanding what that means outside of white girls like Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath sometimes.

My poems are not direct translations of my lived experiences. I’m not sure what a direct translation of my lived experiences would mean either? All poems being a process of omission? Maybe in a way my poems are skewed confessionals.

Pertaining to innocence. I’m not interested in a narrator who is ‘innocent’. I believe that narrators need to evaluate themselves and maybe even incriminate themselves in a way that isn’t always heroic. Or at least, that’s the writing I find interesting. I like a vulnerable narrator and not the facade of a hero.

AT: You have been so deliberate in framing your work and tying it in with your activism, which I think is surprisingly rare in the publishing world. I see a lot of poets, writers, artists – and often young people – making their work and sort of just sending it out into the world and hoping for the best. Can you talk about pushing back on capitalist, white supremacist, and queer-fetishising structures of receiving your work and your voice?

CS: I speak up when I feel something needs to be said and I write about what’s important to me. I talk to the people (often poets) of shared experience and don’t talk to people who are not open to critical and creative conversations. I think my experiences in writing and publishing poetry, as far as who I have attracted to me, has been contingent upon my needs as a person in this world. My activism is built upon my needs for this world.