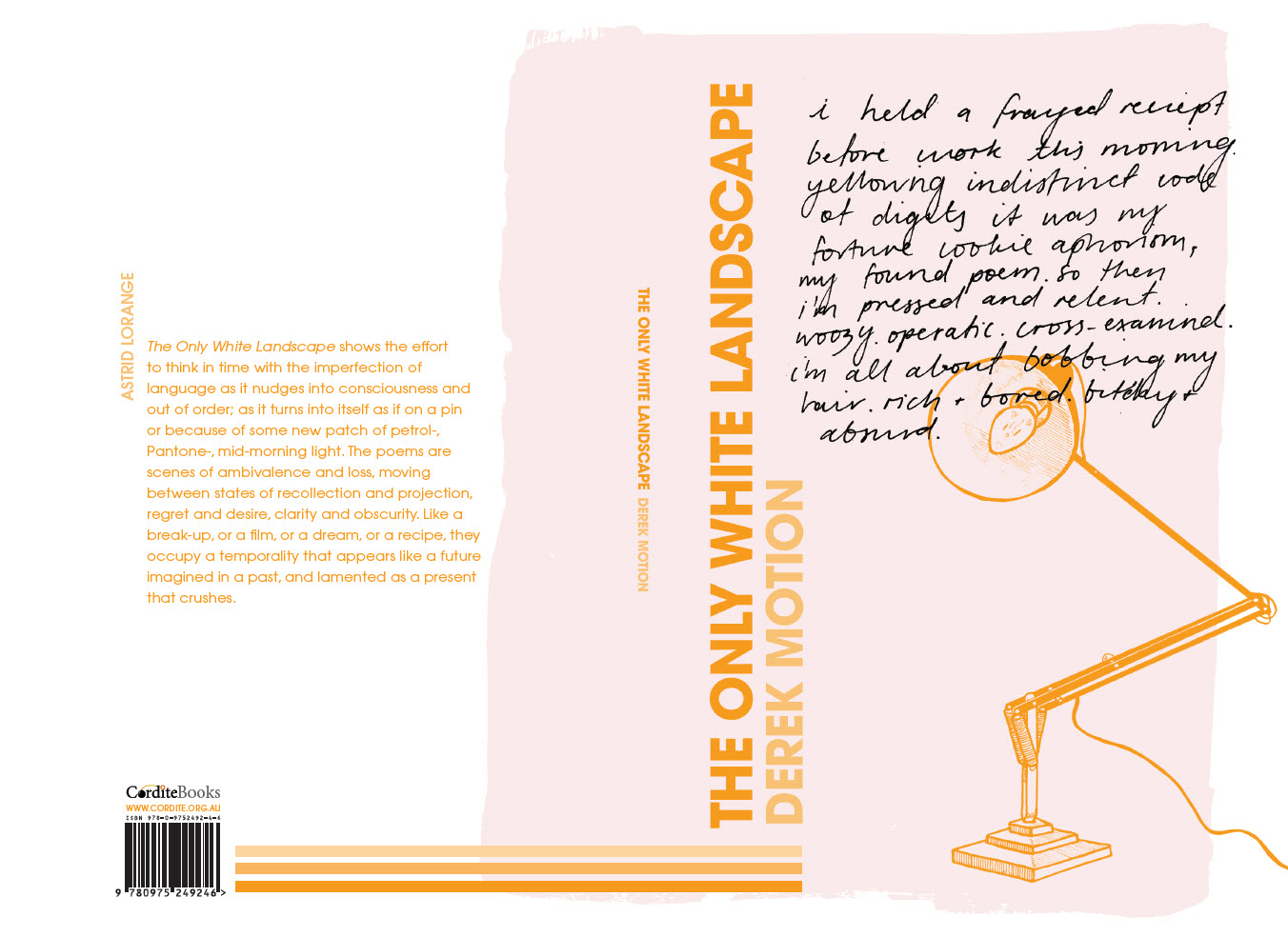

Cover design by Alissa Dinallo, Illustration by Lily Mae Martin

In Gut Feminism, Elizabeth Wilson reimagines melancholia distinct from a conventional post-Freudian understanding. Rather than thinking of melancholia as a feeling-state that registers the loss of something both loved and not-loved – that is, rather than thinking of melancholia as an ambivalent feeling towards what has been lost – she proposes that we think of melancholia as a feeling that actively loses (destroys, forgets, misplaces, denies, erases) what it at once desires and refuses, and therefore, in many ways, is ambivalence itself.

The Only White Landscape is melancholic, in this Wilsonian sense. The poems are scenes of ambivalence and loss, moving between states of recollection and projection, regret and desire, clarity and obscurity. There are preoccupations that link the poems across the collection: bodies (and the clothes they wear, the language of their presence and absence), light (and its close relationship to time), administration (and the twin labours of work and home). Like a break-up, or a film, or a dream, or a recipe, they occupy a temporality that appears like a future imagined in a past, and lamented as a present that crushes. Poems, to paraphrase the poet Eileen Myles, who was paraphrasing someone else, are inventories of prophecy: they write what hasn’t happened as if it were a record of what has been. Motion’s poems are made from partially recalled lamentations that may or may not have been, but which threaten to be felt in / as the irretrievable presence of a memory: ‘later she’ll chew her lip at the verb / manoeuver’; ‘in the lag the over-sharp afternoon / it backlit the tarmac’; ‘earlier & my daughter plays piano’; ‘my future speculative rendered in oils: / heard turned, sci-fi vantage, imagine tigers / this abandoned account’.

The title can be read in two ways, grammatically speaking: there is only one landscape that is white; there is a landscape and it is only white. White is the signifier of Australia’s settler-colonial context, as well as and relatedly a signifier of blankness, neutrality. The whiteness of the title’s landscape cannot escape its racialised reading, just as the landscape of regional New South Wales, or the inner city of Melbourne, or the rail that connects the two, cannot be read without consideration of the race relations on which the very concept of land depends. This book is then, in some way, a study of melancholia in a historical sense, too: the feeling of inhabiting an untenable version of the world.

What version would ever be tenable? Poems trade on this question, a million different variations of it. A poem is, we could say, ‘a physical symptom of trying / to find the right words, maybe –’. Or, to say it differently, a poem is a way of finding a grammar of wrong words made most real: ‘you do have to be lonely’, like ‘a bolting solo in reverse’. The Only White Landscape shows the effort – never more emphatic than in a poem – to think in time with the imperfection of language as it nudges into consciousness and out of order; as it turns into itself as if on a pin or because of some new patch of petrol-, Pantone-, mid-morning light.