Just now, I'm weary of the fractured, playful, tense world of the post-modern, post-language poets, the pomopomopomopony. 15 years back I was delighted to play with my mind in that way, to play with my politics in that way, to play with my ideas of language and literature in that way. But increasingly for me there seems to be a gap, a hollow, another path to follow. Some texts of the disenfranchised want for anchors.

Just now, I'm weary of the fractured, playful, tense world of the post-modern, post-language poets, the pomopomopomopony. 15 years back I was delighted to play with my mind in that way, to play with my politics in that way, to play with my ideas of language and literature in that way. But increasingly for me there seems to be a gap, a hollow, another path to follow. Some texts of the disenfranchised want for anchors.

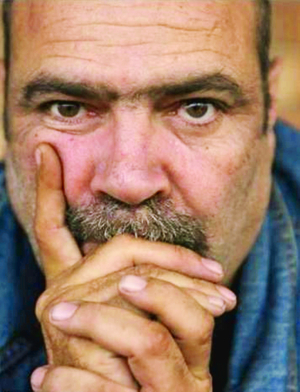

Richard Frankland took the stage in the Famous Speigaltent at the Melbourne International Arts Festival. This was his show ?´The Charcoal Club'. He began with a story and song about his daughter, her birth, her spirit. Behind him we saw projected images of (presumably) his family and others who were dear to him. Thus, he began his performance by declaring where he came from, the people who were around him, behind him, anchoring him – informing him.

It reminded me of the practice which is still alive in India and elsewhere and which was lost to Irish-Australians like myself only a generation or two back: Before a meal, a days work, before any cultural event, the Gods, the devas, the saints, the holy wo/men, the respected ancestors would be invoked to ground and contextualise the occasion in something more substantial that its own noises, something closer to the dreaming.

I was surprised, half way through Richard's performance, when I realised I had no anxiety about him hitting the right notes or stuffing up a song. That kind of anxiety is often with me at live performances. Richard's performance was emerging from a very safe place.

(It bothered me a little that he only fell in love with his new-born daughter after he had blown his spirit under her to let her know who he was – can we only love that on which we have made our mark? is that what the language poets were up to?)

On the afternoon before the show in the Speigeltent, I had been in a counselling session agonising about being trapped in my own harsh self-assessments. Urged to put words to my powerful frustration, the words were obvious; “I want to be free”. The image which came to me was of a young elizabethan prince, walled up alive inside a tower.

Now, 5 hours later, during his song ‘Cry Freedom', Richard Frankland stops and asks the audience to say the word with him; ‘Freedom'.

“Come on, don't be scared.”

“Freedom.”

“Come on, take a breath, breath out…”

“Freedom.”

I'm choking back tears, for him and for me as my word strains for air.

“Once more.”

“Freedom!”

He asks quietly; “How does that feel?”

Paul Grabowsky (on ‘Away', the Radio National Koorie show) described working with Archie Roach and Ruby Hunter on their recent musical collaboration, also part of the Melbourne Festival. Paul was struck by Archie's automatic deferral to Ruby. He would ask Archie a question or present him with a proposal and Archie would turn to Ruby “What do you reckon?” Ruby would sit for a while, silently, feeling it out. Eventually; “Oh, I think that'd be alright.” Richard Frankland, also in on this discussion, told us that he too came from a matriarchal tribe.

Now I wonder whether John Slavin, who reviewed The Charcoal Club for the Melbourne Age ( baby-ish sub-editor's heading ‘Frankland uses Anger as Opera'), may have benefitted by deferring to his partner before opening his lap-top? I wonder what was going on the night he attended? Confronted with the personal, heartfelt, and unpretentious parlour show, the wake and celebration which Michael Farrell and I relished, John Slavin was baffled by ‘the form' the show took. He noticed ‘anger', a ‘history of racism' and a lack of focus. John's review reads irritated, as though for him, Richard Frankland hadn't grasped the refinement necessary to take the stage in a serious festival. Apologies to John Slavin if I've misread him but I sensed in that review echoes of a desire to colonise creativity.

Video monitors, mounted either side of the stage, flickered to life 4 or 5 times during the evening with the talking heads of a group of black and less black Australians commenting, one after the other, on some aspect of the current state of play/war. I recognised names but unfortunately couldn't tell you too many specifics about most of these significant people. Germaine Greer's head popped up on the screen again and again. She is obviously valued. Comment after brief comment. Everything was arranged for effect: it seared.

As I sat there with Richard Frankland's songs, video images, stories and poems, with the skilled musicianship of Andy Baylor, Aurora Kurth, Monica Weightman etc., in this weird pseudo Bavarian tent at the pay-money-to-see-culture Melbourne Festival, despite myself I was coming home to a family inside and outside myself & Germaine Greer's iconoclastic thesis for rescuing this country made a visceral kind of sense.

In her Quarterly Essay last year, Germaine argued that despite the whitey's attempted genocide and consistent battering of the aborigines, the indigenous people have remained open to us, have continued to engage. Because of this openness of spirit, Germaine suggests, over the years indigenous values and ways have infiltrated white culture insidiously. Contemporary white Australians, she argues, are far more enculturated and imbued by the indigenous than we realise.

I recalled a comment made in 1994 by my old friend Dorothy Ferguson. Dorothy grew up in country Victoria loving Dolly Parton, Jerry Jeff Walker and cowboys. So in her mid 20's she moved to the USA. After 10 years away she came home for a visit in ’94 and discovered the pleasures of Melbourne's exploding stand-up comedy circuit. After cackling through a gig one night, we leant on the bar having a drink and Dorothy came out with something that surprised me; “Having been away and come back, it seems so obvious that much of the original stuff about Australian humour comes from the aboriginies – the whole attitude for a start, and what about the timing…” She got distracted and broke off, started eyeing off Greg Fleet.

Germaine reckons the solution is for us whiteys to decide to adopt the indigenous modes more consciously, to let our cultures and our selves be more profoundly transformed and led by their ways; the nation could become an Indigenous Republic.

What came home to me during the Charcoal Club was that regardless of my tribe's on-going conscious or unconscious genocide, the generous indigenous spirit was coming to get me whether I liked it or not, was infiltrating me bit by bit because, like the indigenous Australians I too had been up-rooted, bleached and taken for a fool.

Circumstances generally are much much worse for our indigenous peoples but we've all got the same disease. Aboriginal Australians have been brutalised but we whites are also lost, have also lost our ‘lore', our ‘family', our integrity as a culture. Many of our white young men are killing themselves or lost for meaning & when our hearts hurt we are firstly offered a chemical ‘fix', courtesy of BigPharm, just in case we were harboring the illusion that we had inner resources or that healing love could be found in family and community relationships, or in ‘spirit' or ‘dreaming'.

The indigenous spirit drags at me because like many (most?) of us in 21st century Australia the tap-root into my own dreaming has been eviscerated by ‘civilisation'. But the tap-root continues to reach for water … & there's water out there.

Sitting with Richard Frankland's deep, safe song,

with Germaine Greer's inspired and sometimes silly enthusiasm,

with a warm crowd of white-ish Melbournians in the Spiegeltent

it became quite clear that,although the creations of the mind are wonderous,

the compensatory obsessions(discourses), games(Art) or rages(politics) of the disenfranchised

are not to be mistaken for

the dreaming.

Will Day is a Melbourne writer.