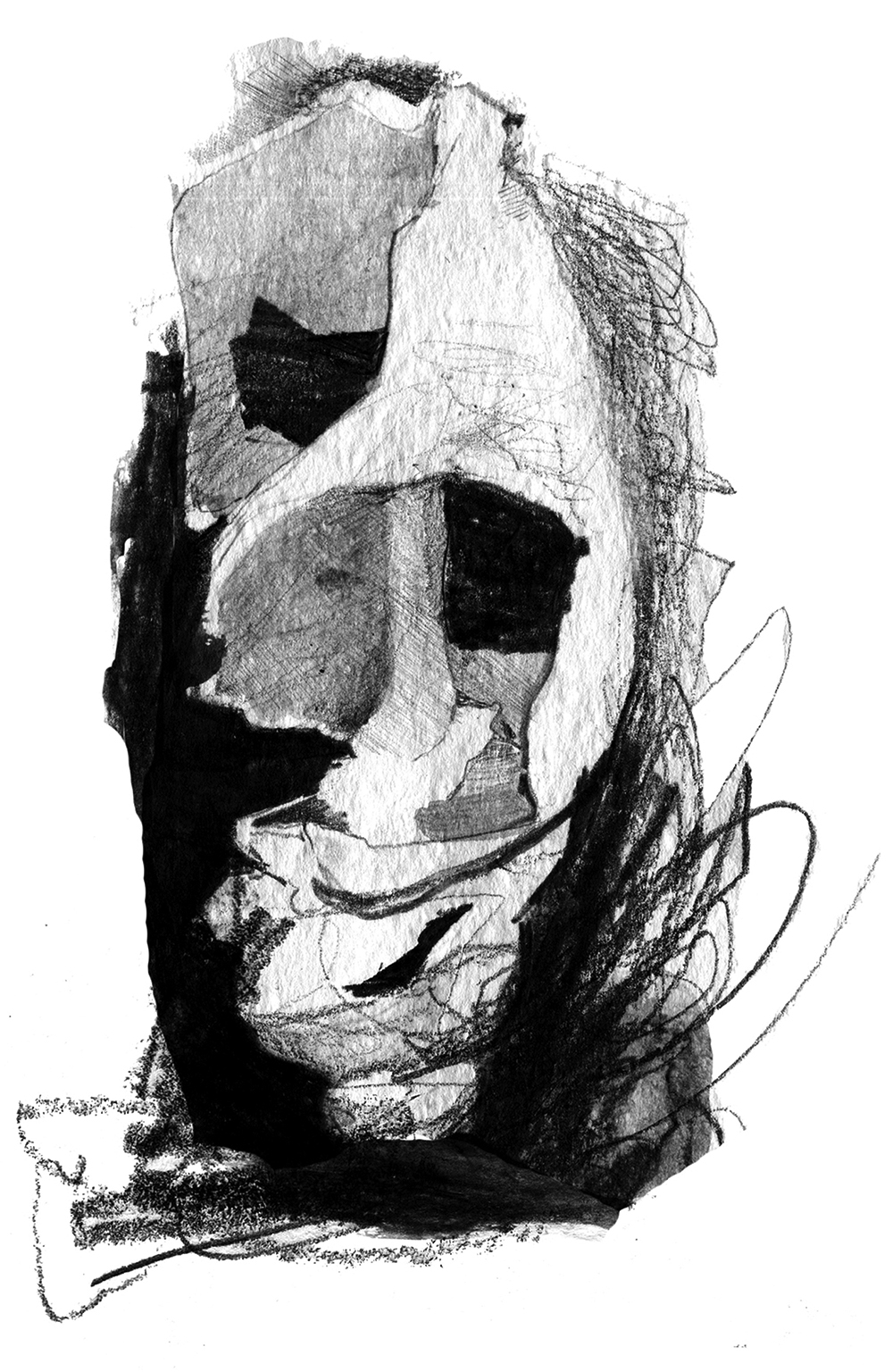

Mel Pearce | Untitled | In response to Alexis Late’s ‘Procedure’

Alexis Late’s ‘Procedure’ draws on the conventions of Confessional poetry by women in English – particularly on the influential work of Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton – to make a creative statement resisting the masculinist imposition of clinical discourses to the raw subjective experience at the centre of this poem: the speaker’s abortion, and its visceral consequences for her rage, guilt, hurt, and defiance.

In stanzas 1 to 3 the speaker begins in conversations experienced as attack, with a metaphor of a hunter trapping an insect, and the speaker expressing herself as insect under threat of being devoured. The insect ‘flutters weakly,’ is ‘blanched’ – a bloodlessness whose significance will become apparent.

In stanza 3 the pursued insect becomes the speaker. The insect is pinned to an entomologist’s board, a cruel skewering of the self, fallen victim to a kind of casual masculinist rationality: ‘splintering / under your gaze,’ ‘single-minded’ ‘with each quick piercing.’ Then a pivot in stanza 4 to the pins that stick women, and the pins that women stick in sewing. Here the connotations are of sewing as a scene of ritualised violence done to women in the prison of domestic conventions stifling women’s autonomy historically. The staccato assonance of ‘pins, pins, to fix, to fix her’ employs repetition to draw out the subtle twin meanings of ‘fix’ as both a transitive and intransitive verb. Taking an object, ‘to fix her’ is the masculinist, medicalised understanding of women as broken objects necessitating repair, and taking no object, with pins ‘to fix’ as in the immobilisation of the captive insect. ‘Sewing her silence / an inheritance passed on’ offer the subtle twin readings of sewing as a silent, normative stifling of women’s expression reproduced generationally, but also a craft made in silence that speaks women’s traumas to the world. These lines echo the portrayal of Philemona in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, who is raped by Tereus and has her tongue cut out to ensure her silence, but weaves a tapestry to expose her violation. The twin status of sewing is one instance of a theme running throughout this poem, which features scenes of women’s immobilisation, women’s damage, women’s injury, portrayed in a way that criticises these practices in a refusal of the theft of women’s expression and women’s bodily autonomy. In the opening stanzas of ‘Procedure’ I am reminded of the conflicted, visceral rage alongside the pins of medicalised trauma in the work of contemporary Melbourne poet and artist Jessica Knight, and, in particular, a photographic work from the ‘Paper Dolls’ group exhibit at the Docklands in 2014. The artist is photographed from behind, naked, vulnerable, before a wall covered with X-rays of her many surgeries, the bright streak of steel implants down the length of her spine, and the punk scrawl of her poems up the wall alongside, wounded and defiant: ‘I HAVE MORE BACKBONE THAN YOU.’

In stanzas 5 to 7 of ‘Procedure’, the speaker, ‘weaving quietude and guilt / while you tell me how you feel,’ defies her partner’s selfish need via the feminised violence of sewing – ‘Still, it seems to me / your mouth is a wound / I want to stitch up’ – and the object of the speaker’s rage becomes apparent: the terror of pregnancy, ‘the frightening consequences / of blood and semen,’ and her injury at her partner’s selfish scorn: ‘I was slipping from / your downturned mouth, / like a stitch from a knitting needle / now futile and crooked.’ The knitting needle again connotes the feminised violence of sewing, but its presence in this line as producing something sloppy and wrong is haunted by the knitting needle as iconic of the feminised violence of desperate, self-inflicted backyard abortions.

The speaker performs a kind of reactionary nonchalance in stanza 8, with the brashness of the imperative mood (‘Fuck the world!’). The linguistic device of chiasmus, repetition with inversion of the word-initial sounds, draws ‘Fuck the world!’ and ‘we fucked’ into a syntactic parallel. This device draws out the disturbing brutality of ‘fuck’ as a verb here, meaning that to fuck someone can be a little too close to fucking up someone. In stanzas 9 and 10 the speaker’s guilt in the wake of abortifacents returns to the feminised violence of sewing, occupying the paradox of a malevolent emptiness, a nothingness that won’t stop growing: ‘I cowered before guilt, / and its threat of emptiness / that gaped at me / like a hole in my stocking, / widening, widening.’

The representation of the violence done to and by women’s bodies in pregnancy, miscarriage and abortion has a long history in women’s art, including in the work of pioneering women’s autobiographical Confessional poets Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath, and it is Plath’s work in particular that Late draws on in this poem. Late’s ‘Your mouth is a wound / I want to stitch up’ echoes Plath’s ‘Blood, let blood be spilt; / Meat must glut his mouth’s raw wound’ from the poem ‘Pursuit.’ So too does the stick of pins echo Plath’s ‘My Japanese silks, desperate butterflies / May be pinned any minute, anesthetized’ from the poem ‘Kindness.’ Late’s poem is on well-worn ground depicting the visceral and emotional gore of lost, aborted pregnancy. In this Late stands alongside contemporary peers such as emerging cultural critic and essayist Leslie Jameson, whose 2014 essays ‘Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain,’ and ‘The Empathy Exams,’ republished in her 2014 collection of the same name, grapple with the inheritance of the aesthetic traditions of women’s Confessional poetry, and with questions of women’s subjectivity and suffering. Depicting women’s embodied pain is always intensely personal, and yet almost a cliché in its frequency and banality, a structural consequence of markedness in an intensely misogynistic world. What lends Late’s account its timeliness and its originality emerges in stanza 10: the speaker’s guy has the gumption to mansplain her own abortion to her by text message. Where Jamison’s narrator in the ‘The Empathy Exams’ wants her nice-guy boyfriend ‘close to her damage,’ to experience her abortion and ‘hurt in a womb he doesn’t have’ (31), Late’s speaker is more sorrowful, a hurt rebuke at the condescending ignorance of this man: ‘When you explained / the procedure to me / so calmly over text, / you dropped my heart, like a rag, / in a pool of dirty water.’ The semantic ambiguity of ‘it’ and the pregnancy connotations of ‘carrying’ in the final lines open a space for a subtle double reading: Regretful ‘I didn’t know you were carrying it [my heart]’; or barbed and sarcastic ‘I didn’t know you were carrying it [this pregnancy, its consequences].’