Young musicians competing for work on the Melbourne pub circuit say that they frequently have to pay to play. The cost of hiring expensive PA systems, lights, trucks, and possibly a manager means that rock ’n’ roll musicians are in the red before they even get on stage to sing the blues. It is a vicious circle. Bands won’t go to the union because every job is regarded as a step on the road to success. The more jobs they get the greater chance they have of getting signed up by one of the agents who control the local scene.

– ‘Young Bands Get Payment Blues’, The Age, March 12th 1981

Bon Scott’s bagpipe-boosted lyrics about life as a gigging musician in the 1970s ring true today – although, really, the bits about being ‘under-paid’ (as opposed to possibly-paid), and stopping in all the byways (as opposed to well-promoted and carefully spaced capital-city shows) now seem quite romantic. This classic AC/DC song featured prominently at the 2010 Save Live Australian Music (SLAM) rally in Melbourne, where the concept for the 1976 Countdown film clip, with band and bagpipers playing on the back of a moving truck, was re-enacted down Swanston Street accompanied by thousands of protestors.

While the 1976 crowd was presumably motivated by the possibility of appearing on Countdown and/or looking up some kilts, the 2010 SLAM crowd was mobilised against proposed state government liquor licensing changes which would classify venues hosting live music as ‘high risk’. This was a large, organised and policy-literate crowd with a local focus, quite in keeping with the flavour of Australian music-scene activism in the preceding decade. But the protest harked back to an era when Australian musicians needed to be street-wise but were highly unlikely to be planning-policy literate.

Shane Homan, an expert on live music policy history in Australia, notes that the heyday of the Australian music industry is dated by many participants as being between 1978 and 1988 (Homan 2000). This also coincides with the ‘Countdown era’ (Duffield 2009; Stratton 2006). This was a period in which some people made a lot of money, and a lot of people went to live music shows in pubs. It’s also the period against which descriptions of live music decline are frequently measured.

This era can be characterised by fewer bands, working more often, and in a conspicuously more (manual) labour intensive and hierarchical fashion. At a distance of thirty years, its day-to-day workings give an impression somewhere between On The Waterfront, Wall Street and Puberty Blues.

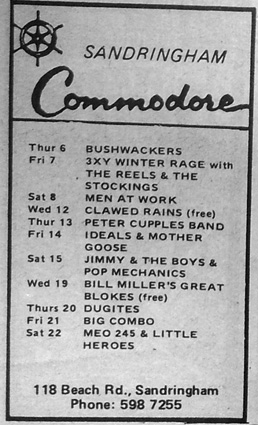

At this stage it wasn’t uncommon – or even particularly high-status – for bands to play several times per week, or on the same night on different sides of town. Gross takings were high compared to the present day, but overheads were tough. Since pubs did not have their own public address systems until later in the 1980s, rock gigs required owning or hiring a (gigantic old-school) PA, and paying for roadies, a lighting technician (!), and a van. A lower-rung band might command $200 per night, several nights a week, or a higher-status band $3000 per night, not adjusted to inflation – figures that would seem downright optimistic decades later. But with many extra hands and equipment costs involved, musicians often encountered the ‘pay to play’ scenario (Milsom, Thomas & Hawkes 1986). Meanwhile, the role of support bands in this was not dissimilar to toilet-seat warmers in English private schools, helping to lug boxes in the wee hours in the hope of one day being on the other side of the door.

While bands were busier with gigs and engaged in more manual labour than they are today, they spent comparatively less time on booking and publicising shows of their own accord. Most gigs were organised by booking agencies, which at this stage dealt with nearly all bands rather than just the bigger names. The best chance for publicity for a new band was to get on the good books with an agency and work up to headline gigs through frequent work around town, and then hope for a hit record and a Countdown appearance to gain national exposure. It was more of a niche inner-city endeavour for bands to approach venues directly or produce their own publicity material, though this would certainly become the wider norm by the 1990s. In the short term the big money, and the path to Australian stardom, lay in the holy trinity of:

a): booking agencies/record companies (often the same, unashamedly vertically integrated, alternately scary or nurturing entity);

b): Countdown (the weekly ABC music television program); and

c): large suburban venues.

In Melbourne, large venues were located in suburbs such as Frankston, Ferntree Gully, Mulgrave, Essendon, Doncaster and Armadale. In Sydney there were large-capacity (or, at least, very crowded, since fire regulations were often flouted) venues in suburbs such as Caringbah, Blacktown, Mona Vale, Parramatta, and Dee Why. Before the introduction of random breath testing in 1982 these further-out venues were handy for drink-driving audiences. Large suburban venues tended to be linked with agencies rather than having a direct involvement by the publicans in booking live music, but the profits and crowds involved were impressive (see: Freeman 1981; Hutcheon 1982). Countdown, the popular ABC music television program running 1974 to 1987, complemented the suburban circuit, as publicans were keen to host household name bands, and took on novice acts on lower profile nights as part of agency deals.

For the 1983 live music maps shown above, this different lay of the land can be seen in the relative lack of inner-city clustering, and the ring of suburban venues, particularly visible in Sydney, the home of the mega profit ‘beer barn.’ Unlike later decades, inner-city venues were part of the picture, but not yet the lion’s share.

While the recording side of the music industry showed signs of waning (or, more accurately, de-bloating) at this stage, nobody was in any doubt that Australian pub rock was profitable and plentiful. Playing frequently held no particular status but was viewed as a means to an end. The prize, at this point, was a recording deal, and then fame and fortune. But a basic four-track recorder (ubiquitous as a budget home recording device by the 1990s) retailed at over $1000, not adjusted to inflation, and recording in a studio was a genuinely expensive proposition. A decade later, the backing of a record company was exciting because it offered chances for exposure and global distribution, but in 1983 it represented, well, recording. And the prospects for bands with a successful record were splashed with dollops of eighties-style optimism, as Australian performers at the top of the proverbial pile were household names: Cold Chisel, Men at Work, AC/DC, INXS, Midnight Oil, Crowded House, Divinyls, Models, Paul Kelly, Hunters & Collectors, Hoodoo Gurus, Mental As Anything, Boom Crash Opera, The Choirboys, et al.

In 1983, Men At Work achieved what had previously seemed impossible, becoming an Australian band with a US number-one single and album. Subsequently, many Australian bands with national-level success chased this overseas dream, but frequently had to start from scratch. Some bands, such as Cold Chisel and Hunters and Collectors, had a nasty enough time overseas to be content with being Oz Rock favourites (‘You Got Nothing I Want’ is Cold Chisel’s tribute to the experience).

Basically, for musicians in the early 1980s live music was a reliable workhorse, offering a life of regular gigs but punishing overheads, powerful agencies, beer barns, drunk drivers, and unabashed arse-licking hierarchies, all operating under the shimmering sun of potential eighties stardom. So, a little bit familiar, but also enough differing norms to the present to make it seem novel. And even more so than today, this was a man’s world. Data from the author’s wider research project estimates that females constituted, at the most, 9 per cent of Australian popular music performers in the 1980s. In a recent Ausmusic study (Throsby 2010) this figure has risen to a whopping … cue sarcasm … 30 per cent.

Australian musicians who were not Oz Rock favourites and who operated outside the approval of Countdown, booking agencies and suburban circuits – perhaps bands with girls in them, or girlish boys – could be loosely grouped as ‘inner city’, ‘punk’ or ‘post punk’, a scene which flourished in the late 1970s and early 1980s and was documented by journalist Clinton Walker (2005) and director Richard Lowenstein (1986, 2009). The buzz period of this scene (1978) is depicted in the historically accurate party movie (how many of these are there?) Dogs In Space. Longer term, performers from this inner-city scene often decamped to the UK rather than entrust their futures to a limited network at home, with well-known exiles including the Go Betweens, Triffids, Moodists, and Boys Next Door (later The Birthday Party). Setting out, as Antipodeans were inclined to do at the time, with the notion that anything in London would be nicer and more civilised, such musicians were often shocked to find that they had in fact been having a relatively good time back home, with food and heating. But by the 1990s, the geographical choice of more independent musicians was to stay in Australia.

A change in mood for the mainstream pub rock circuit started a few years into the 1980s, with the introduction of new fire regulations in Sydney, as well as random breath testing across all states in 1982 (see: Cribb 1984; Homan 2000, 2003; Maddox 1984). At this point the threats to the pub circuit were still viewed in terms of potentially ‘throwing bands out of work’ (O’Meara 1985), or their ‘bread and butter’ (Maddox 1984), presumably because, even if overheads were nullifying, bands were busy, gender-skewed and structured enough to resemble traditional paid employment. But out on the patio, change was crackling over the cane fields …

I’ve always felt in retrospect that we were at the tail end of what we’d call the golden era of rock in Australia. The venues were just starting to change and something was different. People were changing their behaviour, poker machines were coming in, breathalyser. I don’t ever remember people saying ‘wow this is a healthy scene, this is fantastic’. They still complained. But if you compare it to what happened after, it was incredibly healthy.

– Musician active in Sydney in late 1980s (interview July 2014)

Five years ago would we have been interested in (let alone bought) a mini-album comprised solely of unsigned bands, most of whom are based in rural areas? The newest Triple J Unearthed compilation is selling like hot cakes … Post silverchair, if you’re young, talented and ambitious your chances of succeeding have improved.

‘Young Talent Time: The Hunt for the Next silverchair’, Beat, 21 August 1996

As for other features of Western life, the 1990s was a period for Australian music in which nothing immediately disconcerting seemed to be happening, but in which the landscape of everyday life, and in particular one’s long-term prospects in the labour market, were cleverly restructuring. While barriers in global trade increasingly were being removed, live music activity clustered spatially more than ever before. The ‘grunge’ or ‘alternative’ scene (these terms sound very dated now!) emphatically broke into the mainstream in 1992, with the first Big Day Out and Nirvana’s first and only, and of course wildly successful, Australian tour (see: Shea 2014).

Pingback: Bowie in the Pub: How Sydney Music Died - AUSTRALIAN MUSIC MUSEUM PROJECT

Pingback: The iconic Melbourne live music venues we dearly miss from the last 30 years - Beat Magazine