How do you write about a place that’s not known for much – or that is known for being ‘not much’? If the Romantics sought to imbibe the sublime through encounters with wild nature and the modernists hoped to record the shocking dissonance of urban life, it’s easy to forget that some poems reject the easy juxtaposition between such extreme environments and instead delve into the everyday details of smaller towns, or duller suburbs. The histories, bits of natural landscape, poignant moments, and the glaring hypocrisies that second-wave modernists captured in their jagged and expansive works brought texture and intrigue to places like Black Hawk Island, Wisconsin; Gloucester, Massachusetts; and Briggflatts, a hamlet in the Northwest of England. If the representational fortunes of such formerly unsung locales improved with the twentieth-century long poem’s flourishing, more recently even the suburbs have become objects of interest, feeding trends like ‘normcore’ – though their stain is still carefully concealed by young artists and intellectuals hoping to maintain their avant-garde cred.

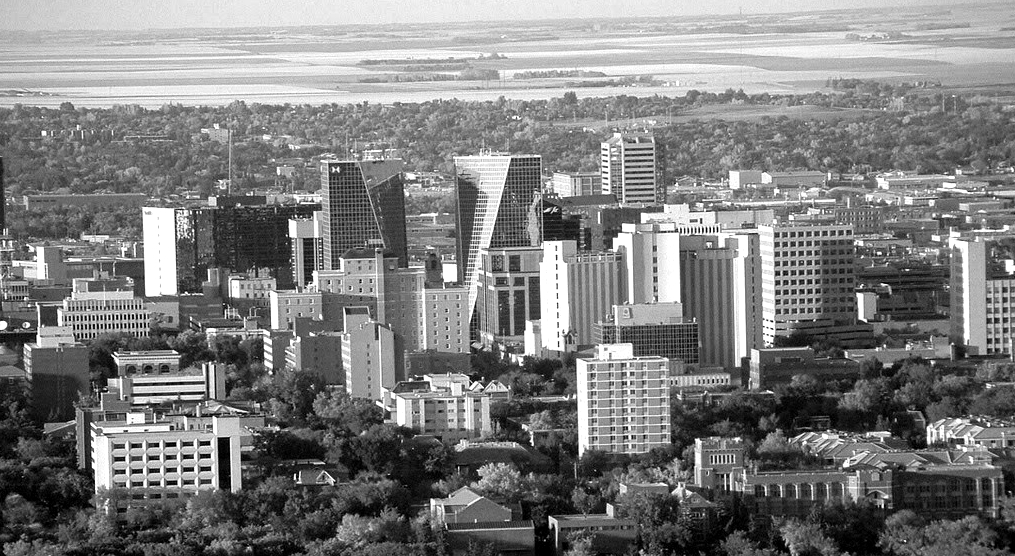

I open this essay with such reflections because my hometown, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada – a place about as ‘normal’ as one could imagine – has recently been immortalised in a long poem by Garry Thomas Morse. Prairie Harbour (2015) is the product of a year and a half spent in the city, which is, to put it colloquially, out the back of Bourke and often perceived as boring, suburban, and culturally irrelevant. Regina is a geographically isolated city of 195,000 people, and is often regarded as a bit of a joke. It’s similar to the areas of the U.S. called ‘flyover states,’ or perhaps to an isolated spot like Alice Springs. But like any area overlooked by – dare I say it? – snobs and elitists, the city of Regina and the province of Saskatchewan punch above their weight in in many areas: as Morse’s modernist-influenced collage makes clear, there is significant history that long predates the founding of the city in 1882, and there is a rich artistic legacy as well.

With Morse, the representation of the city’s history, its regional ecology, and its arts and vernacular culture are in capable hands. Morse is the author of nine books, the most recent of which, Discovery Passages (2011), documented his mother’s Kwakwaka’wakw ancestry, and was a finalist for two of Canada’s most prestigious honours, the Governor General’s Award for Poetry and the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. While I think Morse’s work receives less discussion than it deserves, Discovery Passages was also popularly lauded, and was voted one of the Top Ten Poetry Collections of 2011 by the Globe and Mail, Canada’s newspaper of record; one of the Best Ten Aboriginal Books from the past decade by CBC’s 8th Fire; and it was also recommended by the 2014 First Nations Communities Read program for public libraries across Canada.

The title of his new book, Prairie Harbour, is a gentle oxymoron playing on the name of a new-ish housing development charmingly located on the flight path of the Regina Airport that exemplifies the city’s dull, if undeserved suburban reputation. But Morse offers more than just mockery of what is not-always-affectionately known as ‘the city that rhymes with fun.’ In fact, he pushes back against imputations of suburban mediocrity: his peripatetic ‘I’ wanders from art galleries to orchestral concerts to the library, through the city’s downtown and its trendy neighbourhoods, and along less remarkable streets (including one that was memorable to me because it was where I lost control of the car on a patch of ice on my way to high school). All the while, these adventures in urban geography are arranged in a sophisticated counterpoint with Morse’s archival explorations, aesthetic ruminations, and meditations on contemporary culture and politics.

Some of Morse’s archival routes are traced through his own surname, which leads him to a variety of locations and figures, notably to Massachusetts and Jedidiah Morse, a man whose life spanned the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Here’s how Morse describes him in a poem from the highly fragmented first section of the book:

Morse, père,

‘father of American

geography,’

held the

lectern fast

against French

Illuminati

& wasn’t so keen on the skull-

measuring gloss on Native

Americans in Encyclopedia

Britannica

& hoped for grand

‘civilization,’ blessings

on heathen lands

& happenstance

in his Report to the Secretary

of War of the United States

on Indian Affairs (40)

As this gloss on Jedidiah Morse’s life and work begins to suggest, two key themes of Prairie Harbour are colonisation and settler colonialism. These are very much a part of daily life in Regina and in Saskatchewan, where approximately 15% of the population is of Indigenous ancestry. Morse explores these themes through an accumulation of historical detail that accretes slowly and laterally, but not in a predictable order. The poems skip around through historical time and contemporary incidents, and the satirical middle section, ‘Company Romance,’ traces unexpected connections and creates resonances across a vast temporal scope that runs from the earliest explorers of the North American continent to the present day. Like many other ‘poem(s) including history,’ to borrow a phrase from Ezra Pound, the past has explanatory value for the present, but its lessons can be oblique and indirect.

For example, in a poem titled ‘Matthew,’ Morse reflects on the biography of Matthew Cocking, a seventeenth-century diarist and explorer in the employ of the Hudson’s Bay Company, the chartered corporation that controlled the fur trade in much of North America for several centuries and was at one time the de facto government of what was to become Canada. Recounting Cocking’s exploits (and exploiting his unfortunate last name), Morse offers a humorous characterisation of Cocking’s disparaging views:

whenever he dangled a bauble for a pelt, and found the French had already got there first, he wrote in his journal that the Natives are lying liars full of lies. (62)

If Cocking seems a man of his time, a typical explorer, or even an easy target, Morse traces direct – and more uncomfortable – continuities between Cocking’s moment and our own. He suggests the complex legacy that figures like Cocking have left: ‘one day,’ he explains at the end of the poem, ‘I’d have nowhere else / to buy my g_ddamned pants’ (62). For Canadians, this reference is clear: while Cocking himself may be a minor footnote to history, his employer, the royally chartered corporation that once governed the land, is now a prominent department store in our malls, and it even goes by the same name (although it is more commonly called The Bay). If Cocking seems distant, the company he worked for is very much present and affects us intimately in our urban architecture and even in the clothes we wear.

Morse makes clear that this is more than just a matter of shopping malls: in the final stanza he explains an all-too-common irony: in spite of his disparaging views, ‘Cocking / found the three Native ladies / that were right for him’ (62). Although Morse allows for comedy in this instance, he attends carefully to the legacy of colonisation for Indigenous women, which continues to be particularly disastrous. The poem ‘The Present, Missing’ (which you can hear Morse reading over at The Puritan) is one of the most poignant expressions of this crisis that I have read anywhere. He begins with a plainspoken description of ‘a friend of mine, lovely to be- / hold for being decently real,’ who was ‘on the verge of making a few / changes when out of nowhere / the axe / fell’

(81). This friend went ‘MISSING’ in Regina, and

the local sex workers helped search for her but the police did not though Native folks go missing on snowy evenings all the time (81)

Morse refers to a few prominent crises here. The word ‘missing’ appears five times in this short poem, which frames the friend’s disappearance as part of an epidemic of murdered and missing Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit people in Canada. Activists, artists, and scholars are working to draw attention to this crisis, and have gathered their efforts under the hashtag #MMIWG2S, an incantation that cries out for justice: the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s official review suggests that over the past 30 years there have been nearly 1,200 cases of murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls. However, many critics, including legal scholar and activist Pamela Palmater, have argued that the RCMP’s number is ‘grossly under-counted.’ Morse’s poem also suggests that a broader view of the crisis is necessary. His description of ‘Native / folks go[ing] missing on snowy evenings’ references another frightening tradition: ‘starlight tours’ are a police practice wherein an apprehended person, usually Indigenous, is taken outside the city limits, beaten, and left to make their own way home. In areas where temperatures routinely dip below -40C, starlight tours have often been fatal.