Let your soul stay cool and composed before a million universes.

A line from 1855, first published by Walt Whitman in the poem ‘Song of Myself’, appears again at the beginning of a film produced during a Creative Arts Fellowship at the Australian National University in 19691 Out of the 19th century transcendentalism of New England, the film’s subject emerges as ‘Anarcho-Technocracy’, specifically as it was theorised and transmitted by expatriate poet Harry Hooton (1908-1961). Hooton had died in middle age in Sydney, celebrated as the ‘poet of the 21st century’ by his friends and devotees. In this way, the trans-mediation of his poetry and philosophy onto film seemed strangely appropriate for his ambitious idealism: Leave man alone, man is perfect. Concentrate instead on matter.

In post-War Australia, Hooton’s vehicle to this future was titled 21st Century: The Magazine of a Creative Civilisation. It was first reviewed in December 1955 in the following way:

While there is much that may be pure 19th Century about most of Australia’s literary magazines (in, say, the ‘liberalism’ of ‘Meanjin’, the stuffiness of ‘Southerly’, the rough-neck-ism of the ‘Bulletin’, and the inverted Henry Lawson unionism of ‘Overland’), ‘21st Century’ in this, its first September issue, is at least 20th Century. (Fleming)

Figure 1: 21st Century: The Magazine of Creative Civilisation (September 1955). Edited by Harry Hooton. Design and Layout: Brian Ford and Margaret Elliott. Circulation: Corinne Joseph.

But only two issues of 21st Century would appear (the second in 1957, Figure 1). Following Hooton’s death, yet unbeknownst to them at the time, two of Hooton’s 21st Century collaborators would separately go on to have a significant impact on filmmaking in Australia: Corinne Joseph and Margaret Elliott. Joseph was in charge of the distribution of the inaugural September 1955 issue, Elliott the designer (along with Brian Ford). In 1969 it was Corinne Cantrill (née Joseph) who would make Harry Hooton with Arthur Cantrill, while living in Canberra, after having returned from a four-year stint in London. The Hooton film was intended to be a realisation of the poet’s materialist polemics: using direct film techniques, monochromatic light and hand processing, more than simply a biographical homage to the poet or a retelling of his life, it was an application of his thinking to the medium of film. In Harry Hooton, matter is the issue, the film-strip precedes the projection of light and the amplification of sound in the expanded field of the cinema as an audio-visual environment.2 Alongside the images, Arthur Cantrill composed a series of musique concrète using reel-to-reel tape processing – on a Revox A77 – whereby they understood the recording of sound as an instrument in itself. Their Nagra and Ferrograph machines allowed for feedback to mix into the synthesised sound. 3 Interspersed throughout the heavily abstracted and post-processed montage which organises the film, are audio clips of Hooton speaking as if from beyond the common grave in which he was interred; he had recorded 510 minutes of his poetry and philosophy to tape from his death bed, now available as digital audio through the National Library of Australia. The film, made 50 years ago, has since faded into historical obscurity. However, like the figure whose influence reached far beyond the poets and polemicists of Australia’s east coast (as Sasha Soldatow set out in the editorial introduction to Hooton’s Collected Poems in 1990), the Cantrills’s films have made a significant impact on a form of cinema variously known as ‘avant-garde’ or ‘experimental’ not only locally, but around the world, as recent retrospective screening programs of their work in Spain and Germany attest.

Artist-film and its relation to poetry is a principle concern of their early work, But the links existing between the practice and production of the two in Australia during the 20th century have not yet been established (see Laird). This may be because the Cantrills prefer ‘particular screenings’ of the hundreds of films they produced over five decades, and they have tightly control their distribution. Yet Harry Hooton remains important in that it represents a way into their fiercely independent work. It was screened in public as recently as June 2019 at the Arsenal in Berlin (see Stein). Furthermore, other than for the occasional presentations of the film, there is very little literature examining Hooton’s concerns for the 21st century, his poetry and philosophy of ‘Anarcho-technocracy’.

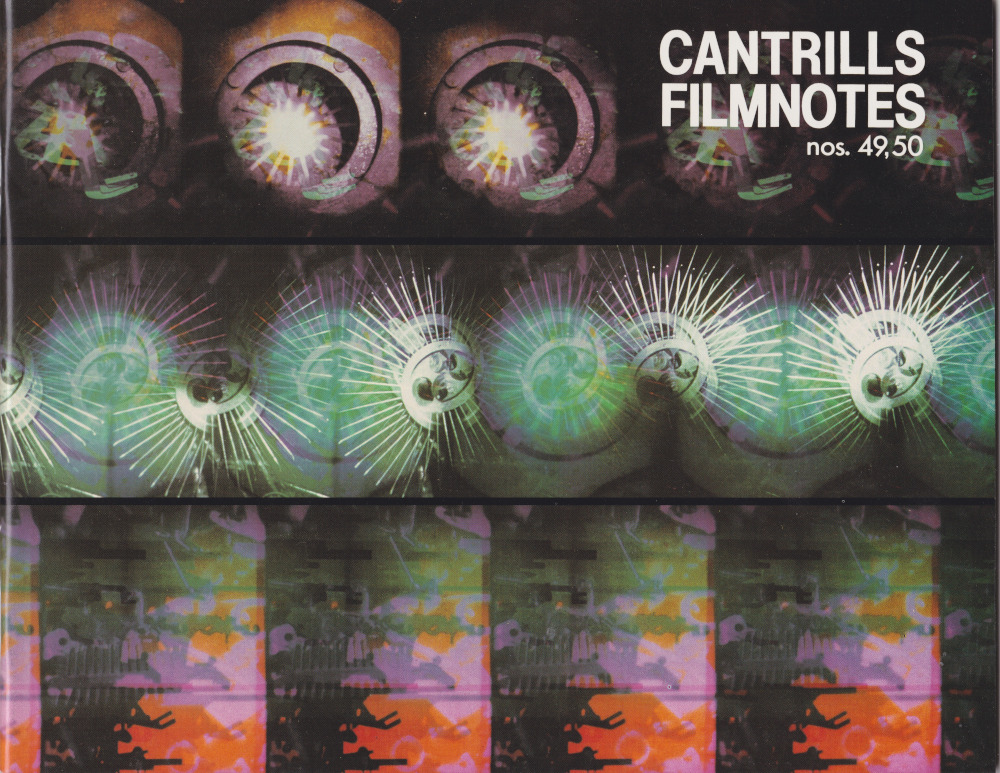

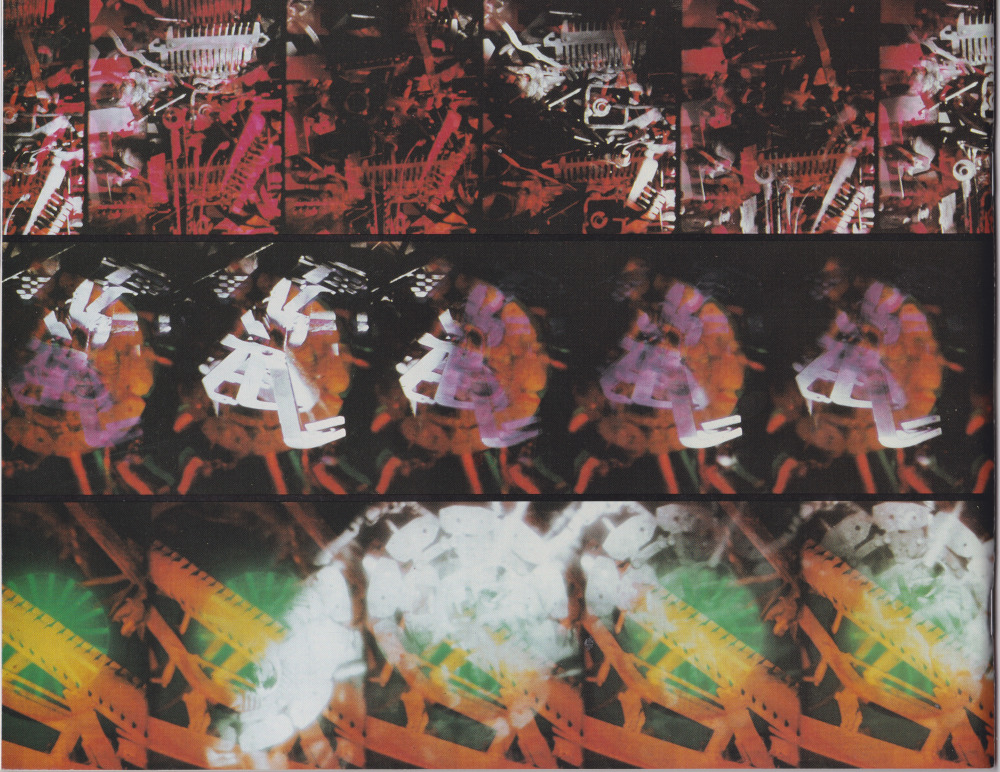

Figures: 2A & B. Front and back covers of Cantrills Filmnotes, Nos. 49,50 (April 1986) featuring images from Harry Hooton (1970) by Arthur & Corinne Cantrill.

Cinemapoetry

In 1986, on the occasion of the fiftieth issue of their journal, Cantrills Filmnotes, Arthur and Corinne Cantrill returned to Hooton, placing stills from their feature-length work on the front and back cover of the issue (Figures. 2a & b). The decision was self-referential: in the same year as they’d made Harry Hooton, they’d published a ‘Cinema Manifesto’ in the first issue of what would become a 30 year publishing project, by quoting Hooton there too: ‘LOVE MATTER TO DEATH, LET IT FEEL YOUR BREATH’ (Arthur Cantrill, ‘Cinema Manifesto’, 3). In 1970, the Hooton film had premiered at the Canberra Film Society, screening in the Copland Lecture Theatre at ANU on the 2nd of September. This was five years after their first ‘overview screening’ by the Brisbane Cinema Group, run by Stathe Black, which occurred before they had headed to London to work in film and television.4 The Cantrills’s first films appeared in 1963, cautiously navigating the conventional documentary and pedagogical forms (one early film, Mud, was shot in New Zealand at Rotorua’s thermal springs).5 In 1969 they had returned to Australia, resolved as to what they needed to do, the first issue of the Filmnotes appeared in March 1971, not long after the Hooton film’s premiere. In it they declared: ‘We want to make films which defy analysis, which present a surface so clean, so hard, that it defies the dissector’s blade’ (Arthur Cantrill, ‘Cinema Manifesto’, 3). Fifteen year later, inside Issue 50 of the Filmnotes, the Editors’ Comment reprinted the first lines of Hooton’s ‘Poetry’:

There are no rules for poetry Necessity makes, and breaks all rules. (Hooton, ‘Poetry’, Poet of the 21st Century, 101).

Their aim for film was the reconciliation of form and content, and the enduring influence of Hooton’s unique mixing of poetry with philosophy presented itself as a significant and local model for how to do this. Furthermore, they’d both seemed to coalesce around and figure out how to articulate the energies emanating from the unique conditions that had produced the amorphous scene known as the Push in post-War Sydney.

During the Second World War, Hooton had come to believe artists were the truly anarchic figures who could thus be the ‘technicians’ required for the benevolent administration of things in the industrialised dictatorship to come. At the same time, a teenaged Corinne Joseph had taken the chance provided by the wartime economy to study botany as an unmatriculated student at Sydney University. Australian cinema during the war years was dominated by the films of Charles and Elsa Chauvel, and the adventure documentaries of Frank Hurley. Yet, as Danni Zuvela has shown, there are also a number of early films made in Australia that ‘illuminate the conditions leading into the development of organised systems of experimental production, distribution and exhibition’ of film here, leading to the moment in the 1960s when experimentalism would take flight (2).

Arriving in Sydney in 1948, the Czech artist Dusan Marek began to produce short films in the early 1950s, which were directly influenced by European Surrealism, in turn an aesthetic response to the totalitarianism from which Marek had fled (7). Corinne had travelled in Europe after the war – at one point working with the International Youth Brigade on the Dobuj-Banja Railway in Yugoslavia – before returning to Sydney and eventually working in childrens’ creative leisure centres (Pinguim). Meanwhile, Arthur Cantrill had met Hooton through his work in the same programs in Sydney in the late 1950s. By that stage Corinne had already been associated with Hooton through his publishing projects, and when, in 1959, she and Arthur were both moved to Brisbane to work with disadvantaged children during school holiday programs, they moved in together and turned to collaborating on filmmaking, which followed from the theatrical activities they had devised for children (Arthur had for some time worked in puppetry).

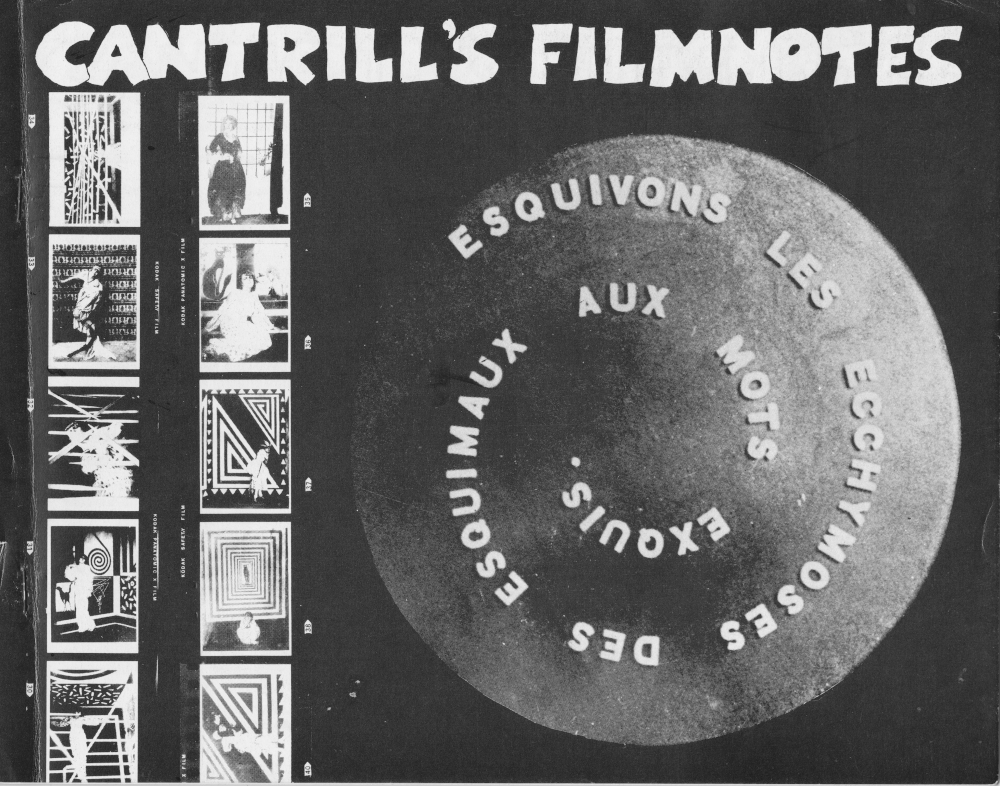

Figure 3: Front cover of Cantrills Filmnotes, Issue 1 (March 1971).

The other figures listed alongside Hooton in the first issue of the Cantrills Filmnotes (later it became simply Cantrills Filmnotes) are more recognisable as the artist-film luminaries that one would expect as reference points for such a journal. Fellow expatriate from the South Pacific, Len Lye, is there. The Cantrills had encountered Lye in Europe in the 1960s, and the link foreshadows their concern for the growing idea ‘pan-pacific’ artists in the global imaginary. Other canonical touch-points include Marcel Duchamp, whose Anémic Cinéma (1926) appeared on the cover of the first issue of Filmnotes, beside images from the even earlier artist-film Perfido Incanto (1917), directed by Anton Giulio Bragaglia. Bragaglia was associated with the Italian Futurists, and the manifesto of 1916, La Cinematografia Futurista, was translated at ANU and included by the Cantrills as the final text of the first issue of their journal (Figure 3)6 It therefore remains a quirk of this moment that the man they celebrate as one of their ‘mentors’ has since that time all but succumbed to the vicissitudes of a minor history. Hooton, as well as contemporary poets like Jas H Duke, Garrie Hutchinson, and Charles Buckmaster would come to provide the Cantrills with direct links to the performance of poetry in post-war Australia, even as they continued to explore new media, particularly on film and video. Most significant for this development, it seems, were the events held at The Maze, a countercultural venue for artists, for selling crafts, books, and even food in Flinders Street, Melbourne.

- The research for this essay was made possible by the Centre of Visual Art (COVA) small grants scheme. The author would like to thank Arthur, Corinne and Ivor Cantrill, Michelle Carey, Angelika Ramlow and the Arsenal in Berlin, and Cordite Scholarly Editor, Brendan Casey. ↩

- A related ‘Exhibition of Expanded Cinema’ at The Age Gallery, sponsored by the National Gallery of Victoria, was held between the 8th and 27th of February, 1971. As an outcome of the Creative Arts Fellowship at ANU, this series of installations and cinema events should also be seen in relation to the Cantrills’s Harry Hooton. See ‘Expanded Cinema,’ Cantrills Filmnotes, 1 (March 1971): 4-5. In part it appears the Filmnotes were issued as ‘expanded’ notes for the exhibition of their work, which included a number of artist and student collaborators, as well as early video works. See Stephen Jones, ‘Video in the 1970s: The Decade Before the Digital,’ Video Void: Australian Video Art. Edited by Matthew Perkins. North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2014, 36-40. ↩

- See the liner-notes to Arthur Cantrill, Hootonics, LP (sham074), Shame File Music, 2014. This is a collection of the music the Cantrills used as the soundtrack to Harry Hooton. ↩

- It is possible that this screening largely consisted in the short educational documentary films for children they had been making for the ABC, including a ten-episode shadow puppet production of Homer’s The Odyssey. See ‘Interview with Arthur and Corinne Cantrill,’ Astronauta Pinguim, 28 February 2014, Sao Paulo, Brazil. Accessed 4 April 2020, online ↩

- For the Cantrills filmography see http://www.arthurandcorinnecantrill.com/filmography.html ↩

- ‘La Cinematografia Futurista’ was first published in Milan on 11 September 1916. It begins: ‘As the book is such a primitive form of thought communication it is doomed to disappear with the cathedrals, museums, palaces and the pacifist ideal.’ It was signed by F T Marinetti, B Corra, E Settimelli, A Ginna, G Balla, R Chiti. Given subsequent events, not limited to the First and Second World Wars, it now seems particularly in poor judgement to reproduce the provocations of Italian Futurism as the touchpoint for the historical avant-garde in 1960s and 70s Australia (especially following the Tet Offensive during the Vietnam War). Nevertheless, in Sydney at the same time, Ubu filmmaker Albie Thoms’s first feature-length experimental film was titled Marinetti (1969). The two films – Thoms’s and the Cantrills’s – therefore force the respective subjects of their work into an uneasy equivalence. See Peter Mudie, ‘Albie Thoms (dissimilis aliqua alia),’ Senses of Cinema, 66 (March 2013). ↩