White Clouds, Blue Rain by Oliver Driscoll

White Clouds, Blue Rain by Oliver Driscoll

Recent Work Press, 2021

White Clouds, Blue Rain (2021) is Oliver Driscoll’s second poetry collection, appearing a short year after his 2020 I Don’t Know How that Happened. Like his earlier work, it is concerned with the everyday: small moments of domesticity and care; conversations both mundane and profound; fleeting interactions with, but more often, observations of, an outside world whose parameters are undefined, but which nonetheless feel tightly bound, contained. To say that this is a result of the pandemic, which has certainly imbued domesticity and its imaginary with a gravitas denied to it when it was considered womanly, would be incorrect insofar as Driscoll has always had an eye for the ordinary, has always been pulled by the intimate, the close.

If the collection has been affected by the pandemic, it might be seen in a slight shift in focus between I Don’t Know How that Happened and White Clouds, Blue Rain – while both dwell on interactions between people, the former is briefer in this, whereas White Clouds lingers and returns. Relationships, as much as the quiet maintenance of home, are central to the collection in a way that cannot be easily disentangled from the isolation and distance imposed by Covid-19: relationships to kin, to neighbours, friends, a lover, as well as to writers and artists and their work; existing relationships, experienced either in memory or within a proximal radius, or one-sided relationships are entirely maintained in a contactless abstract. We meet few strangers in White Clouds, though we watch them.

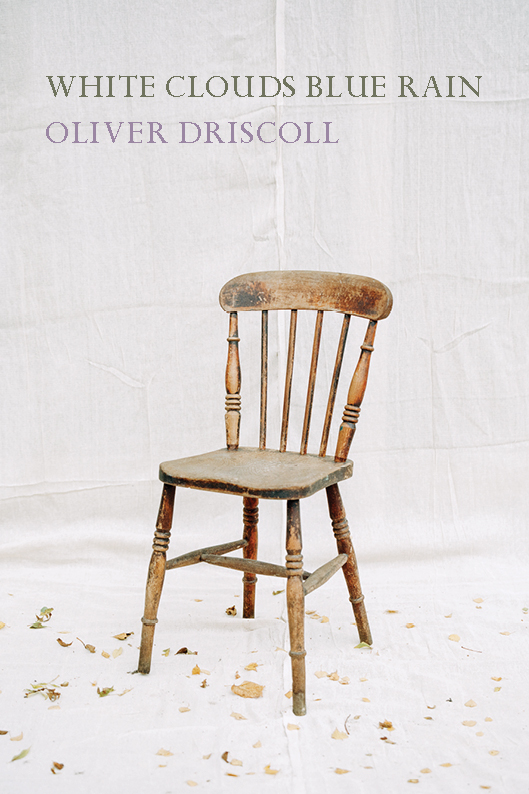

The collection is structured in a series of triptychs: a poem, a piece of extended prose, a black and white photograph, all untitled. These images, especially, add to the collection’s sense of disconnected melancholia. Mostly, they are photographs of a domestic made eerie through greyscale: the acute corner of a roof against sky, the cluttered corner of a room, windows flooding light into an over-saturated corner. Corners, actually, appear and reappear in these images, betraying a preference, perhaps, for the clean lines of the geometric. Indeed, the triptych structure is rigidly maintained throughout, glitching only in the last section when paragraphs break into the poetry, temporarily jostling the stanzas aside. The effect is inconclusive; something is undone but nothing is loosened. The slip is not jarring because the poems, like the sections of prose, are direct, unassuming and restrained. At their best, they are spare – almost thin – yet dexterous and surprising, as in this stanza in the collection’s last poem:

By now we know that not only do

eggs and bottles not have to look like

eggs and bottles

but

they don’t need to be painted at

all

These poems are not the main event and do not pretend to be. They are the deep breaths before launching into speech.

Perhaps ‘before launching into a monologue’ is more apt, a monologue in which domestic mundanity is given sumptuous expression. Everywhere there is the enumeration of things tidied, cleared, fixed, put to order, of books read, conversations had, thoughts idly pondered. It is deeply comforting to read of Driscoll cutting back ivy on a fence, pulling rubbish out from the back of his property, feeding his neighbour’s cat or taking out the compost. To encounter such simple acts of care over and over is nurturing in itself. Likewise, his relation of numerous conversations feels like having the radio on, a constant, comforting buzz. The conversations themselves vary in theme and emotional resonance and, at times, can feel a little contrived – a little too well turned and clever. Whether or not they are faithful representations of what was said is often beside the point: when they work, they are elegant and profound, as when he recounts his mother’s reaction to her grandchild breaking one of her ceramic pots: ‘Some pots, she wrote, have a lifefulness, but most do not.’ Even when these reports feel as though the borders of truth have been bent, the bending can be dismissed for the grace Driscoll offers us. For example, when Driscoll describes a conversation with friends, he relates a young woman he hadn’t previously met saying that ‘When it’s raining heavily or just cold and damp, she has the sensation that memory is located on the other side of her apartment walls.’ I cannot bring myself to care whether or not this was actually said, it is too moving an idea to not be repeated.

Driscoll’s interest in the small and near, taken with his direct, sparse style, engenders a curiously untextured world, albeit not a flat one. It’s rather that his sentences are so unadorned and clear that they necessarily draw straight lines and distinct shapes. They have the effect of an Edward Hopper painting: simple, restrained, still, melancholic in a diffuse, unspecific way. Dreams, memories and observations are recounted in the same tone, and relationships are conveyed through conversations recounted at a consistent anthropological remove. Everything is drawn along the same perspectival plane, everything equally close while being observed from the same distance. Depth accrues over the reading, as a mood or general vibe. There is no meaning, per se, but it feels like it.

In my favourite prose section, for example, Driscoll deftly interweaves anecdotes about camping with his father with fragments about boys lost in a New York sewer, a friend pulled from a river by his father, catching yabbies to eat, going to call his mother and not calling his mother, a broken piano key and others, each turn building a gentle tension that reaches its climax with Driscoll deep in a cave, inches away from a hole whose bottom is far too deep. The section is exemplary of how the collection as a whole is disconnected from time, moving across years in graceful loops, dipping into dreams, ruminations on books or art, conversations and snippets of life, unsituated yet accruing. The digressions are many and at their best, they are tangible: grounded in a history that is intimate and lived.