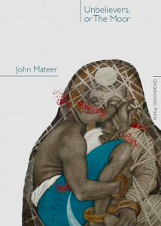

Unbelievers, or ‘The Moor’

Unbelievers, or ‘The Moor’

by John Mateer

Giramondo, 2013

Emptiness: Asian Poems 1998-2012

by John Mateer

Fremantle Press, 2014

In his two most recent books, the prolific John Mateer presents work developed over the long haul. His concluding essay in Unbelievers is a reflection on the seven years of writing behind that body of work, and Emptiness emphasises in its subtitle the 14-year scope of that collection. Despite the years of writing they represent, both collections bear a freshness of focus, expressed through Mateer’s formulation: ‘the irony of Elsewhere’.

As the the books’ titles suggest, an idea of ‘the East’ is central to Mateer’s project – one concerned with invisible histories, cultural translations, meetings and exiles. Barry Hill’s endorsement of Emptiness lauds Mateer as, ‘the best guide I know to the poetics of travelling in what we call Asia.’ While Hill rightly directs our attention to the invented nature of the zone known as ‘the East’, I’m inclined to suggest that rather than a guide, Mateer’s work represents a poetry of unsettlement, where constructs of both ‘East’ and ‘West’ become equally disorientated. Calling into question the historical contingencies of territory, Mateer’s poetics are alive with the contradictions and contested histories embodied by particular places. More than guiding, therefore, the poetic gestures are archaeological; disturbing and unsettling the surface meaning of ‘Elsewhere’.

One of the main features of Mateer’s poetics of unsettlement is a conceit I will describe as ‘decomposition’. Appearing in various guises across both books, decomposition represents an ephemeral, ironised state in which the significance of an historical or formal construct is revealed at its moment of disappearance or decay. Unbelievers foregrounds this process in the book’s third poem, ‘The Books’:

Not all books were thrown on the bonfires. Some, as Ibn Zunbul recounts, were stored in abandoned mosques. Our Traveller, hearing of this, was led to a mosque, And through the keyhole saw nothing, But heard – not wind – the rustle of worms. Maybe, he thought, all books are the Uncreated?

The poem’s emphasis rests not upon destruction as such, but rather the temporal process by which things eventually become undone. When things decompose they become something else, but what they become often tells us much about what they were. This process of metamorphic change can illuminate the elemental parts of the whole. In chemistry, ‘decomposition’ is a term that generally appears with an object, denoting an analysis of the constituent components of a substance (for example, bacteria decomposes milk into its solid and liquid elements). I borrow this particular meaning of the term to suggest that Mateer uses poetic language to ‘decompose’ history’s manifestations – the nations, states, empires and languages that result from the conflation of space with ideology. The narrative of conventional history transforms into a narrative that reveals gaps and contradictions. In Unbelievers afterword, Mateer comments that:

You could say I am interested in lost histories. I wouldn’t really see it like that … I wouldn’t think so much in terms of lost histories, rather in terms of histories that appear and disappear, and histories that are influential even if invisible.

Drawing a swift analogy between history and language, and echoing the writings of Daniel Heller-Roazen, Mateer continues that as with history, it is never entirely clear where one language begins and another ends. Similarly – and intrinsically to Mateer’s work – poetics mirrors this horizon of appearance and disappearance:

We have the material – the form – of how we think words should be composed to be a poem, and those words themselves, whether naturalised loan- or foreign-words, all that elusive material. And besides, both might come to us twinned in the media of sound or writing, with their own heritages and constraints of performance.

Decomposition acquires layered meanings then, relating to a notion of historical analysis, but also alluding to the poet’s approach to formal composition. The poems in Unbelievers and Emptiness develop a compact between the two, where the functions ‘analysis’ and ‘composition’ propose analysis as decomposition. The figural manifestations of rotting and wearing away are reinforced by the use of decomposition as poetic method, which positions the material poem at its own reflexive point of decay.

The actual term ‘decompose’ appears in the seventh poem of the ‘Monsanto’ series of Unbelievers:

Roof, lime-lichened tiles and rotten beams, caving-in, then the walls, maybe, though they decompose like music

The series comprises of twenty-one short, untitled poems enigmatically related to the contemporary terrain of the Portuguese village of Monsanto. Superficially an account of a location seen through a traveller’s lens, on another level the poems are highly attuned to the temporal dimensions of place. At times the speaker recalls an abstract journalist, a poetic foreign correspondent reporting ‘at the scene’. On one hand there is an imperative to mimic conventional journalism to tell a story as it is happening. Bold opening lines such as, ‘You are still dreaming’, approximate journalism’s perpetual present through the continuous tense. On the other hand, time fills numerous dimensions – it has depth and solidity, it inhabits the landscape. The speaker of the Monsanto poems reports a split, spatialised time:

Two bell-towers, both ‘clocked’. Between each pealing of their hour a few minutes’ discrepancy that you allow to be infinite, or Monsanto

As with the line, ‘decompose like music’, the pause between the two bells expresses decay through sonic metaphor. The poetic utterance is characteristically Mateer: matter-of-fact, while at the same time firmly abstract in fixating on this moment between meaning and un-meaning. The poem produces an imaginative interval that spans the ideal and the actual (the infinite/Monsanto). Placed at the edge of temporality, the speaker initiates a decomposition of Monsanto’s history. In the interval between the two bell-towers, the speaker reports at the scene of history’s unmaking. But what is the scene at Monsanto? What has happened?