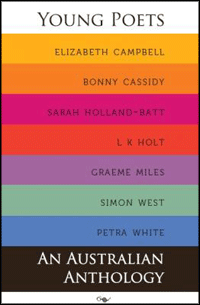

Young Poets: An Australian anthology, edited by John Leonard

John Leonard Press, 2011

I’ve respected John Leonard Press since its beginnings in 2006, and over the years a theme has formed across its publications. Leonard’s poets have a lot in common. There is nothing slapdash about any of them. These are poets clearly enticed by language and by the theories of life. Don’t expect rhyming. Don’t expect clichés. And do not, above all, expect anything simple.

Let us begin, as Leonard has in his press’s new anthology, with the incredibly skilled Elizabeth Campbell, whose poetry is as textured as it is precise. Though I mean that summary to be a compliment, I cannot help but feel that I’m missing some emotional connection with Campbell’s poetry – as if her writing is precise almost to a fault.

Take this excerpt from ‘A Mon Seul Desire’:

Ashy heron, fallen magpie face off, and both are hunted by the falcon. Myth we reject turns inward – the selfless lover loves no self in his other, loves only love, ends folding on himself, ceremonial: love’s mind loves its own luminous terminology: you, only, I, we, two: my sole desire ...

It is final lines like this which can make my heart grow large, as if it were a lung taking in new air, but we cannot read a single line of poetry in seclusion to the rest of the poem, and it’s the rest of the poem that distances me from what ‘desire’ might imply. It’s clearly a very complex word, and it would appear as though Campbell takes a round-about way to get to the heart of the matter.

She goes so far beyond the word that I become lost, and it is this persistent manner of interrogation which has me re-reading stanzas, trying to follow implications. Understanding that this may be the way Campbell’s mind works, tenaciously incorporating philosophy and mythology into her poems, I find it interesting that her writing style is so sparse. In fact it might be why I find her to be such a fascinating poet, one I admire. I just can’t feel her poetry.

Onto Bonny Cassidy, whose imagery is intoxicating, if you can only be patient enough to follow it through. From ‘Range’:

There’s a slip

incised into the bank – a deep shelf

wedged well with kindle and roll, some of it bunched up

to roots, some flipped –

under the rim of earth and wrack

a slip cut round the sandstone skirting: no rushing cavers

(that bird was landing in a puddle, after all)

just a deeper crevice swallowing striped chips of shale.

An opening for some kind of

except it ducks in from the bank

and turns a few metres down,

back to the bed

sinking clack and drop in currents of gravel.

Instead of light there’s air

getting higher and

oaks shedding themselves

into dark, thrown circles.

Her style is visually intense and demands close – too close? – reading. And this leads me to the crux of my critique. John Leonard chose an alphabetical ordering of poets, and Campbell and Cassidy just happen to be the heaviest. As they represent the first two of the ‘young poets’ whose work, according to Leonard’s introduction, ‘ensures the serious continuance of an art that is possibly vulnerable from being too little read’, I begin to feel intimidated. There’s an intellectual approach to these poets’ work which erases any chance of gut and instinct, and I’m immediately feeling their weight.

When I reached Sarah Holland-Batt’s section I found relief. This is not to say she is easy or accessible because she does take us out of our comfort zone with emphasis on foreign soil, but still there are moments of everyday speak that I find great comfort in after the intensity of Campbell and Cassidy: ‘Five years I lived / by that black mountain range’ (from ‘The Idea of Mountain’) and ‘Noon, / I bring the mail in’ (from ‘Letter to Robert Lowell’). It is so nice to finally feel less of an outsider and more of an ally. We read in ‘The Quatrocento as a Waltz’,

Open the window: outside it is Italy. A fat woman is arguing over the artichokes, someone is dying in a muddy corner, there’s a violin groaning in the street.

This writing is clear, the images so plane (however out of the ordinary), that the poet’s world on the page becomes our world as well.

LK Holt returns us to the intensity of the first two poets, leaving Holland-Batt to be that memory of splashed water on our faces. As her pen name gives little away as to the question of her gender, so do the poems fail to lean toward an obvious male/female slant. One half of her poems are about males, with four beginning with the word ‘He’ and one – my favourite, ‘Unfinished Confession’ – about a male wishing himself sexless and genderless. Holt shuns the ‘I’ in the personal sense and holds fast to assuming new identities. When we think we might grasp a bit of the poet, it is in the form of the pronoun ‘we’, in which the poem is again about someone else (the second half of the ‘we’). Holt promotes the personal stories of others, rather than of herself, and narrative and content often triumph over imagery in the process.

Leonard writes in his introduction that, in the case of the poets in this anthology, ‘the momentum of the poem is not so much inward, towards a presented self, as outward to a world and its mysteries, of being and of language’. I’m a fan of Holt’s and have no doubt she should be included in a book which showcases not only our best young poetic talents but our best poetic talents, but in the case of this anthology, I feel pairing her with Campbell and Cassidy in the first half of the book, means that too much of the ‘outward’ is overload. I find it difficult, then, to not compare Young Poets with Felicity Plunkett’s Thirty Australian Poets, which also aims to highlight today’s young poets, and make the judgement call that the later is a better production for its overall diversity.

Another negative of the alphabetical ordering is that the structure ensures we only hear female voices for more than half of the book. It jars at first, but when you reach the end of the collection you realise that Graeme Miles and Simon West aren’t only situated too far down the ABC procession, but they are indeed the only males out of the seven poets. Quite an interesting statement on today’s young poets, when historically the case is the opposite.

With Miles it’s very personal – however personal surrealism can be. In his poems it’s as if the physical body diverges from the rational and enters into absurdity. Examining its parts rather than its whole, new perspectives emerge, as in ‘Body’s Poem’:

I read the body’s poem in different ways. Thinking from the centre of the chest, I peered up through a swan-like, periscopic neck. While thinking from the belly and the crutch became an old drunk or a cat.

Miles compares the human body to those of various animals again and again in his short selection, suggesting primal instincts are more than sexual desire and the nurturing of an offspring (thought he goes there as well). Sometimes the body becomes disassociated from the soul, as in ‘Isis and Osiris’, in which a man at a party jumps into a box, which is then dumped into the sea:

Somehow his body breaks up through whole countries. Fingers worm their way into soil and deserts. Toes curl up under their nails like snails. Limbs turn tree ...

The man’s wife puts him back together and we see the power of love and the vulnerability it yields as ‘though in bed at night / he creaks where he’s mended’. I could attempt a reading of ‘Talking Glass’, begins with these lines:

I went to find pasta for the wary to prepare their pianos. I tried to speak, knowing that I’d spoken pasta in the past, but now there was broken glass between my teeth.

But interpreting this poem would mean that I might have to reach too far. I could say that the mouth works mechanically, that speaking – apologising – is what is socially acceptable though in essence is nothing more than words as useless as shards of glass, so the mouth and heart are disparate entities, but I might be trying too hard. Nothing is simple with Miles. But his work is a lot of fun.

Simon West is the nature poet of the group, but to say his poems are simply about nature would be wrong. The focus is not the apricot tree, but what a person can learn about himself and those around him through the apricot tree; there is a symbiosis West seems to be working with. Birds make an appearance in more than half of his poems, but not one single poem uses a bird as its focus. Such is the case for language, or rather the absence of language. For West, a poet dependent on words must accept silence into his day. In ‘A Minor Sense’ ‘you’ must block out the cacophony of the neighbourhood to find your way to meditation:

an awareness of surroundings, and through a window without curtains a light glows in your own empty room. You know when you take a deep breath and can feel the air? Well, that’s how it is, here, in place, at the end of the day. But all this, is it told in praise? And on what grounds? And it’s gone, as you circle in.

So once you begin to interrogate, forcing words into the empty room of your mind, that perfect moment is gone. West’s poetry is about recapturing it. As with nature needing man in these poems, the absence of language needs the presence of words. It is a case of the after being of no use to us unless there was a before, and I find this idea very spiritual.

Petra White fits into this group of young poets not only in age but also in the way she steps outside of her poetry, reserving her words for others. Yet there is little distance to cover in reading a poem like ‘Woman and Dog’, for instance, if you begin with an outsider and want to reach the heart of the poet. I feel as though I am capable of understanding White more than any of the poets presented in this anthology, and recognition can be a major factor in liking (that is going beyond admiring) a poet.

In White’s work, we see a young girl playing in the water in ‘Ricketts Point’ and though White is not in the poem, we know she realises the joy of abandonment. We read office memos and, though White does not claim to be one of the workers, we see she’s aware of how business and commerce run our lives. We see a kangaroo and, well, this is where I have to change gears. White is so talented that we begin to think she must live in a kangaroo refuge, or work in the field of animal linguistics, or was once in a former life an actual kangaroo!

And here I end this review, giving thanks to the alphabetical ordering of the poets for at least giving Petra White the perfect opportunity to end the anthology: a good one, an important one, but at times a bit too much like a text book.