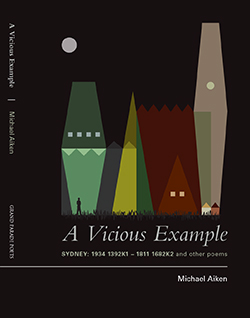

A Vicious Example by Michael Aiken

Grand Parade Poets, 2014

It’s 4 am. Nasruddin leaves the tavern and walks the town aimlessly. A policeman stops him. ‘Why are you out wandering the streets in the middle of the night?’ ‘Sir,’ replies Nasruddin, ‘if I knew the answer to that question, I would have been home hours ago!’ – Rumi, ‘On the Tavern’

Reading Michael Aiken’s A Vicious Example is like walking out of the pub and wandering city streets at 4 am, half-drunk and in sub-conscious wonder. The strangeness of it all: What year is it again? Where are we? Aiken’s collection is fragmented, forming thought-voices into obscure imagery that settles and unsettles on the mind. Aiken’s voice is lethargic, hopeless. There is only one narrative to this text that I can find, which from the beginning locates us and the poems in the Australian city. In the opening poem Aiken welcomes us to ‘come and see …’ what the rest of the country looks like after colonisation’s ‘Theft by Discovery’.

The collection’s language remains as plain as concrete and as layered as the city’s façade:

This city is like this country – broken bricks built over with steel, glass and nylon – the entire tumbling edifice propped precariously on a sandstone bed swarming with restless spirits. (‘The Macarthur Line’)

Reflecting on the work, I look outside of it, to MTC Cronin, Pam Brown, Lachlan Brown, and Greg McLaren. Bonny Cassidy also mentioned these poets in her launch speech at Melbourne’s Collected Works; I would like to further some of those comparisons here. On McLaren’s The Kurri Kurri Book of The Dead, Nicolette Stasko wrote, ‘I find myself marvelling at what I have ‘never seen’ though I recognise it as home. He can make beauty out of empty Coke bottles.’ This is the poetry of Aiken, too; however, for me, Aiken gets even closer to a city’s chaos – a mess which is reflected in the book as a whole. It is disruptive in layout, the sections are confusing and don’t fit together – like a post-colonial city. Aiken’s city is beauty-less: it’s too real. Have I seen it before?

Aiken is less about humanity, and more about its affects: chaos. Take the poem, ‘Object’: ‘A shell / is. / And, now that I have said so / it cannot be undone.’ His poetry is not the in-between, of, say, MTC Cronin’s in possession of loss. It is also not giving voice to the out-there as in Anthony Lawrence’s The Welfare of My Enemy. Aiken, in a sense, is more about the present. He gives presence to voices that surround us everyday but are rarely heard. Their sounds sway betwixt the living and the dead – in nature, in us. The work creates a cacophony that morphs into embodied feeling: mosquitoes being zapped in neon lights, burnt rubber, sunburn crackling into skin, city ghosts moving, rats crawling, ravens spying, and then death. Like drains which:

breed fleet mosquitos and feed the hungry frogs (‘Drainage Ponds’)

– and engender re-birth:

Off white Ibis

feed frogs to their young (‘Interlude’)

Throughout the book, Aiken uses the life cycle of nature in the concrete jungle as a way to focus on the co-existence between human and other organisms. I believe he gets closer to ‘showing’ the reader this than Tim Low does in The New Nature – to which Aiken makes reference in the collection. For example:

Off white Ibis

feed frogs to their young

in the fronds of a palm

on a Macquarie Street lawn

a man in a suit leans against

pissing in a cavity

of the trunk.

Tourists half hearted

sunbathe in the park

hardly long enough to burn. (‘Interlude’)

Re-reading, I wrote ‘brilliant’ beside ‘Interlude’. Why did this poem speak to me? The humour? I imagine frogs feasting in the fronds watching a suited man pissing into a tree; this image is hilarious. It’s one of many images that I have seen before – but haven’t noticed until now. It’s also the seriousness of the pissing metaphor that appeals. Maybe the cavity represents the city itself. Maybe my thinking of it as brilliant is seeing the cavity as a suburban swimming pool. Aiken is dragging us out of our half-awake urban state: ‘Fairy wrens scramble when ibis honk together / and death is averted / by the timely careening of a caterer’s van / with no time for wildlife’ (‘Palm Grove’). I think of the thousand trees removed for suburban pools, about the death of that wildlife, and the thriving of an-other: ‘A family of silvereyes camps out in the lantana / drawn closer together as more houses build up and out / like a dragnet / or a pod of dolphins closing in on little baitfish’ (‘Allagai’). We are all of us, Australian humans, a vicious example; but we exist here, don’t we? This is the question I hear Aiken asking.

As another young whitey, I’m unsure of my inherited role as occupier. Now, when I look around, all I see in us are Aiken’s ‘professional tourists’ (‘1732 5II2KI). Thus, I can’t help reading the ‘silvereye’ as an allegory for us settlers – you know, the diasporic nature of these migrant birds. Aiken invites the reader into exotic suburbia: ‘one thousand tiled pools / sunk in sandstone or scalloped out of clay’ (‘Take a step in exotic suburbia’). Lost in its sprawl I have forgotten about the start of the book – its centre? – the brilliant opening poem mentioned at the start of this review.

‘Theft by discovery’ creates a depressing image, haunting, and immensely sad. It sets a hell of a mood. The poem represents the beginning and the end of settlement: the city is chaotic, diasporic; it is impossible, and was always going to be from the start:

Our white whale is red and swims out there, through the sand. Her side is harpooned in several places then they’ve been chained together so people can climb. (‘Theft by discovery’)

The language is dry, like that country. The metaphor is huge, literally. I think of Daumier’s Gargantua (1831), where the French artist depicts King Louis Philippe the size of Uluru, with the people – taxpayers – walking a plank into the King’s giant mouth. By beginning the collection with the poem above, Aiken (I think) attempts to set his work, and us whiteys, free, by affirming our being as occupier. Aiken confirms this land as stolen, harpooned. The poems that come after ‘Theft by discovery’ swim amongst its affects, trying to make sense of the bloody mess that was/is the social experiment of ‘White Australia’.

That poem’s mood, its brooding on place, informs the collection’s pace. Throughout A Vicious Example reflections of identity are met with slow, deathbed-like breaths, and then, sometimes, optimistic interjections:

Each day is its own and only anniversary to celebrate (‘Anniversary’).

Whilst reading Aiken’s work I see myself in the city, heightened. The other day, on Sydney Road in Melbourne, I was riding my bicycle and observed poet Tim Wright, reading and walking toward a tram stop. Time paused. I wondered what volume of poems he was reading. And then I thought about this review, of how I want to write it walking, sipping coffee, in the city – in the real time where we read books nowadays. I thought it too superficial to write it cooped up in a library. I felt it, too, must be real and as sporadic as Aiken’s documentations: a new way of seeing myself in the city, and of seeing us: ‘We angle like fish, / manoeuvre to get a glimpse / of those with the bait’ (‘Sixty-nine poems’); or ‘You must be / an asset / to your employer / what with your business suited / rebelliousness / and your mohawk up your ass’ (‘Translations from the English III’).

This latter stanza struck me. Aiken makes me think how challenging it is to pursue a life of creativity, and of respect for an-other. From here – in the thick of the city’s smoke, trying to make some art – it would seem much easier and more rebellious to conform to a status quo. Fuck art. Fuck the environment. Fuck wildlife. Fuck the past. Fuck the red whale. Let’s walk all over her. The real punk is Aiken’s man in the suit, with a mohawk up his arse, and even his brand of punk is questionable: ‘Doesn’t anyone work in / this city / or are we / all just using / it for art? (‘07452352K2’). And, on a new thought (the poetry manoeuvres us once more), Aiken’s got me thinking of those colonial ships, with their cabins full of rum: ‘When I read what you’ve written / it makes me think / that you’re one of the greatest drunkards / who ever lived (‘Translations from the English II’).