And to Ecstasy by Marjon Mossammaparast

And to Ecstasy by Marjon Mossammaparast

Upswell Publishing, 2022

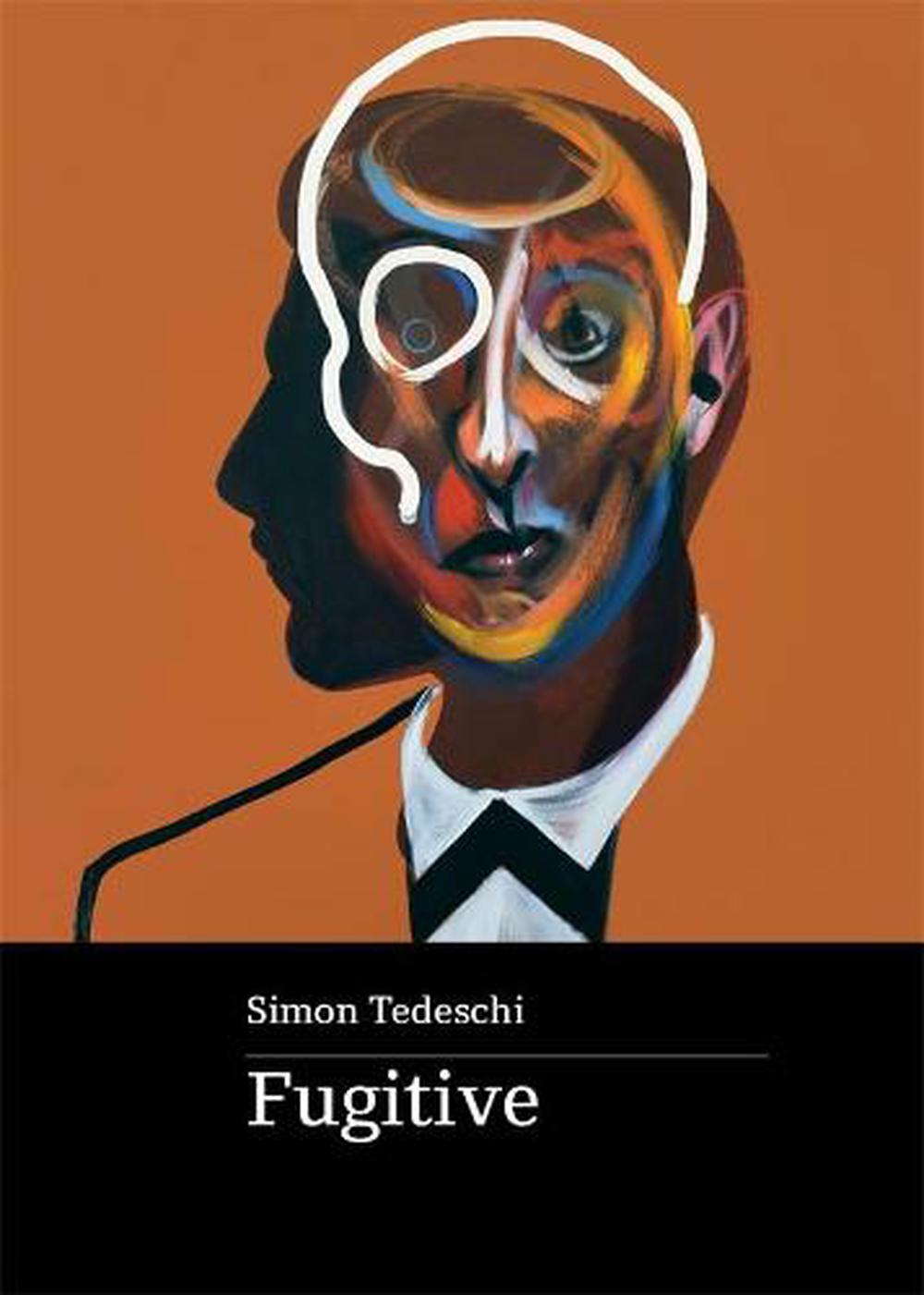

Fugitive by Simon Tedeschi

Upswell Publishing, 2022

In And to Ecstasy and Fugitive, Marjon Mossammaparast and Simon Tedeschi testify to psychic realities concurrent with place, realities that overflow Australian and international borders. Both books hinge on altered states of consciousness. Both are arranged in segments self-described as “pastiches” or “fragments” (Tedeschi 20; Mossammaparast 87). The books are consentient in exploring migration, cultural lineage, and home, but they bifurcate in distinct destinations: art (Tedeschi) and divinity (Mossammaparast).

Mossammaparast’s sculpted poems form sections that build to a conclusion, whereas Tedeschi’s meandering, book-length sequence cross-references itself continuously. Physical orientation on the earth is an ecopoetic and spiritual issue for Mossammaparast, whereas Tedeschi inhabits a more sociocultural, psychological ecosystem. Tedeschi’s ironic ruminations contrast with Mossamaparast’s passionate evocations, and the poets’ techniques differ vastly.

And to Ecstasy, Mossammaparast’s second collection, is an agile plunge into literal and figurative transportation. Shortlisted for the 2023 Kenneth Slessor Prize, it follows her acclaimed debut, That Sight (Cordite Books, 2018). And to Ecstasy proposes a “place outside of place / we never arrive, set into motion / without will, called to will” (76), a place in which Mossammaparast progressively locates her readers by moving us through a series of geographically specific vignettes into an integrated field of transcendence (59). The effect is one of hope. Human precarity is experienced with joyful surrender rather than grief or fear: “how beautiful it is to have an empty Centre / […] / not filled with names, but where rain falls / and spirit is the being moving hands” (16).

Mossammaparast’s voice is ecological, concerned with religious and cultural tradition, situation, and relationship. And to Ecstasy challenges geographical and perceptual boundaries, building from one world of literal travel to another of spiritual travel, and threading these together with glittering anaphoric images of water, fire, mountains, trees, bodies, and fishing nets. The book comprises of three parts. ‘[There]’ is an international travelogue in poems, ‘[Here]’ sifts through interior and exterior Australian landscapes, and ‘F i e l d’ takes an overview of embodiment and prayer. Each section is marked by herald poems that formally announce progression from zone to zone. For example, the closing poem of ‘[Here]’, ‘At The Gate’, uplevels the reader’s perception of place and simultaneously declares the poet’s intention for the next section:

glow this highest heaven, and I will live in the confluence of a miracle, on the tip of the spire catching charge with lightning, in all directions. You, and you, and you, beyond the paper and the words are also now lightning: this is what Love looks like, from here. (58)

Literary references to Emily Dickinson, Seamus Heaney, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī sprinkle the book’s 88 pages, identifying a few of Mossammaparast’s influences, and the ‘Notes and References’ section is a short but welcome guide to the poems’ more obscure content. To add subtext or scripture to her poems, Mossammaparast employs concrete shapes and offsets some columns in italics.

In the first section, ‘[There]’, visions of fire frame a preoccupation with matters of religion, politics, and the environment:

it’s the apocalypse in my thoughts, charred koala tufts that break this green relief, a northern season still in equilibrium. It’s cinders of kangaroo in my eye, embers shaking paradise out of trees. Forget even the homes on fire, that may be rebuilt: it’s the Open of Hand and the Destroyer on the doorstep (14)

And, floating like smoke to the right:

ashes to ashes dust to dust (14)

This section bears witness to diverse international climates and customs, for example, in Scotland, the poet “dreams of pipermen / skipping the Outer Hebrides / here to fall, to drowning” (24). In Italy, “in the Garden of Eden / a cycad grows / […] / that sprang before Australia” (31). In Iran, political and social unrest “flares in the sky, / radiant cells of children / burst alight in air” (21).

The second section, ‘[Here]’, plays with directional motion as a threshold for expanded consciousness. Australian culture contrasts with life in the rest of the world: “Australia dreams of a new carport, / a beat up ute to transport the fridge into the back yard, to mull the sea, / the Christmas pudding” (46). Water imagery is prominent as borders and spatial planes begin to merge. “God comes with clouds, in winter beams that fan / into the spectacle of genesis. Masts clang / against the slapping sea” (56). Mossammaparast now addresses her god directly: “We I call you, never made, but true, in the realm of forms […] /And I would have loved you to the palimpsest of blue mountains / your light holy, winged outside of” (43). Australia is spiritually “large, durable, extravagant, / the scale of megafauna. Confounding as platypus. / Countries still defining their prayerlines” (48).