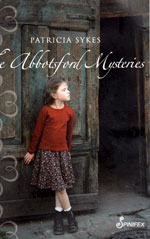

The Abbotsford Mysteries by Patricia Sykes

Spinifex, 2011

Patricia Sykes’ fourth collection of poems, The Abbotsford Mysteries, is a lyrical working-through of the experience of girls and women at the Abbotsford Convent in Victoria. While the site (located on the Yarra north of Melbourne) is now an arts and cultural hub, it served as a Catholic girls’ home from the 1860s until the 1970s, run by the Sisters of the Good Shepherd. The convent was built at the beginning of the twentieth century, and operated as a boarding house and school for ‘wayward’ girls and women, orphans, migrants and girls from rural areas. Given this context, it’s hard to read and react to The Abbotsford Mysteries without relating it to recent revelations in the media regarding the prevalence of child sexual abuse in Australian Catholic institutions, and the eventuating Royal Commission into such abuse. The poems work over ‘unfinished things’, making a space where ‘the best/the worst [and] the unspeakable’ cohabit. Particularly charged are the absences Sykes courts: girls who died, girls who ran away, poems that deal with sin’s structuring around power, silence and routines like prayer and chores. But these poems are also preoccupied with survival and escape, especially through activities like dreaming and wondering, as ‘Bad girls do the best sheets’ suggests:

cleanliness is next to Godliness is not always spotless some of our trough dreams ending as scurf some popping like soap bubbles a few living long enough to dodge the Bishop’s Parlour

Sykes writes in ‘Mortal, venial’, ‘In this humid confessional / everything is epic’: as a resistant discourse, Sykes’ lyric is a fragment art and resists the ‘tell all’ quality confession implies. But these poems are also public poems, and appeal to the plurality of experiences of an ‘our’, composing a collective lyric . The collection should also be considered as an example of documentary poetics. Throughout the poems, other voices and fragments of direct quotation from interviews – Sykes interviewed over seventy women for the project – are woven into the poems, marked by italics. This device is effective, although a little repetitive (are all quotes the same?). She has also used numerous other documentary sources, which leaves me wondering about the huge amount of supplementary text and memoir that couldn’t find a place in these lyric poems, but might have a place in prose poems, biographical poems or fictocritical work.

The Abbotsford Mysteries is striking in its range of sympathy. What emerges from these poems as they move through the different ‘classes’ of women is a sense of women’s solidarity, a hybrid identity that includes both internal subjugation and suffering but also resists exteriors of religious experience and patriarchal expectation. ‘As if women are rivers’, Sykes writes in ‘Coils’; ‘As if we fit together like old shards / … / in a history of broken glass’. Nonetheless, the collection is structured around the use of Catholic material, but it is adapted for other means: for instance, each section of the book ends with a collaged gloria. When Sykes’ uses the forms and vocabulary of religious experience, it is not to mount a direct, sacrilegious critique, but to voice a kind of irreducible experience that includes religion. This is most evident in the final section of the book, ‘The Glorious’. This is also the section with some of my favourite lines, those involving animals (‘Our docility is a crocodile’, ‘Trusting the Donkey’) and gardens. From ‘Having lost all fear’:

Having lost all fear the nuns carry on a loving disobedience (they know church men are also children) while on a table top of sand a needle keeps working a beautiful big supper cloth with poinsettias all over it the miracle of becoming a garden where there was none so that when the last supper comes around again we are certain to be flowers.

The Abbotsford Mysteries is an important book for the material it works through, sometimes beautiful and often sad; for this Patricia Sykes derives our praise.