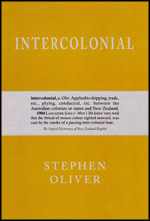

Intercolonial by Stephen Oliver

Puriri Press, 2013

Intercolonial, a new book-length poem by Stephen Oliver, focuses its attention on New Zealand, Australia, and the sea that lies between them. With sweeping long lines, Stephen Oliver zooms in on the details of place and geology: the poem is full of cinematic pans over landscape, seascape and human history, fulfilling what is often a purview of the long poem in naming the world and its inhabitants. His tight focus is evident from the very first lines of the poem:

Tusked cauliflowers and herded carrots, onions in piles, tumbled pumpkins, potato scree, boxed and stall in between scales that swung and creaked from the cream cabin roof of the Indian greengrocer’s Bedford truck ...

This close-up leads us to follow the truck into the streets of Wellington, and then to follow the unfolding map of the city as its roads, buildings and natural landmarks come into focus. We see the ‘council-red, No. 8 Brooklyn-west bus’, and pass under ‘Radio ZLW, the telegraph station on/ top of Tinakori Hill’, before looking out over the water. Reaching Wellington Harbour, our sense of timescale expands as we recognise the slower pace of oceanic and geological time unfolding beneath human history.

At the centre of the work is the figure of the poet’s great grandfather, Thomas McCormack who, leaving Melbourne, ‘sailed for Aotearoa in 1877, clouds in lit pews before him’; Oliver, like McCormack, has adopted a Trans-Tasman existence, spending long periods in both New Zealand and Australia, and his interest in history and the transactions between these two former colonies (the book’s title is not just reflective of the colonial status of these countries, but was a New Zealand term specific to shipping between the Antipodean lands) makes McCormack a fitting focal point. Nonetheless, other historical figures haunt the work, encountered through their passing contact with McCormack. In particular Solomon Blay, the ‘hangman at Hobart Town’, looms large in the centre of the poem as a figure McCormack encountered in boyhood, and subsequently encountered in dreams. Upon being granted a pension, the executioner ‘sought retreat first in Melbourne, then England’, yet remained ‘unable to escape his past’, just as the many hanged had been forced to face up to their own. With his identity as a hangman following him to Britain, Blay returned to Tasmania, taking up his trade again well into his seventies until he ‘died on August 18th, 1897, pauper.’ Blay remained for McCormack a ‘ghost’ haunting him for ‘years to come, a solitary figure, passing through his dreams.’ So it is that the hangman takes up residence in Oliver’s poem, and cuts a larger-than-life figure, overtaking, for a time, McCormack as a person of fascination.

Combining detail, quotation and a long line throughout the work, at times Intercolonial feels like it sits at the edge of prose: this is particularly the case when Oliver ventures into landscape and its markers:

Across the great western land bridge, north, to boulder strewn plains around Mt Taranaki, grassland and scrub, flax lined swamp dominated, interspersed with a few isolated ‘cloud forests’ on spurs; the silver, red, and black beech kidney and crepe fern, tree palm; the mountain cedar and yellow pine, totara, kahikatea, holding to valleys below the tree line, the gravel and sand wastes folding back to Cook Strait Narrows, and beyond, its eastern shoreline.

Such densely detailed passages mark the poem, its line-breaks feeling more determined by desired length for the line than by the layered meanings they create – yet the near-fanatical detail in each section combine with the layered segments to zoom in on different places and figures. This allows everything but the current subject of Oliver’s taxonomies to drop away, and become the poem’s strength even as they can frustrate. The overall effect of the book is akin to a montage of deeply explored moments, and the occasional prose-like quality of the writing makes the work feel like a hybrid between prose non-fiction and narrative poem. Each section forms a stratum of the poem – both as it exists and the unwritten, un-writeable, complete poem of the Antipodes.

The poet notes he has worked on the poem since the mid-1990s; Intercolonial feels like it could be a work of continual expansion, a continually unfolding, obsessive examination of place and personal history within it.