Opera by Stuart Cook

Five Islands Press, 2016

In the poems of Opera, Stuart Cooke attempts to take the writing of place into new territory, and in doing so, accomplishes something remarkable. This collection is both substantial and complex, enhancing our understanding of what a poetics of landscape can encompass and the capacity of language to articulate it.

Cooke has long been uneasy with the label of ecopoet, as he mentioned in a 2014 interview for Peril Magazine. While his previous collection, Edge Music (2011), focused on writing from the geographical and historical edges of landscapes, Opera pushes beyond an attempt to speak ecologically. Cooke is one of many innovative Australian poets (Louise Crisp, Peter Minter, Michael Farrell, Martin Harrison, Bonny Cassidy) who have been attempting to find new ways of speaking about landscape that acknowledge the multiple histories landscapes can possess: environmental, cultural and colonised. Cooke creates a new vision of how to speak about the temporal, geographic, ecological and cultural histories of land and, in the process, expands our lexicon with which to express them.

The cover image grants the reader an excellent entry point from which to understand the key themes of Opera. The artwork by John Wolseley is a detail from a larger watercolour of the spore-bearing bodies of Cytarria in Tasmania and Patagonia and their Northofagus hosts. These plants symbolise the ancient biological connection between South America and Tasmania and, as such, perfectly represent the scope and objectives of this collection. In these poems, Cooke is viewing Australia and South America as landforms once connected as Gondwanaland – ancient landscapes whose shared geological, biological and genetic heritage is still expressed today. Rather than focusing on regional specifics or local endemism as means of expressing place in a particular space and time, Cooke adopts a macro-perspective, writing from an understanding of place that spans millennia.

But these bald mountains remain the wisest: their acrid soils skid through seasons, shirking the heavy texts of jungles, of cumbersome timber, of carbon’s tiresome routines. They lie across the azure like gods of the stone they cradle, they lap it up like great tongues that descend into a single throat, to the mad populous of the rapids, the willows and the bamboos draping, the swirling pollen in aphotic bivouacs, the flames of sun in leaves, where all sound’s reduced to a pure molten sign (‘Valle de Hurtado’)

These poems explore the myriad connections that link the continental fragments of Gondwanaland. Cooke’s overarching perspective sees not just trans-Pacific ecological associations but also political, cultural and linguistic linkages that have, over time, evolved in ways akin to biological speciation. All of the poems in the collection are creative responses to particular regions, but the geographic specifics are not necessarily mentioned in the poems. If the reader is keen to know which landscape inspired a particular poem they must consult the endnotes. I found this to be a cunning strategy, since by not making the poems’ geographic locations explicit, my sense of the multiple levels of connectivity and relationship existing between the various regions was constantly reinforced.

Cooke’s perspective acknowledges regional differences and environmental complexity while also honouring the languages that articulate their ecological individuality. Observed from this macro-level perspective, the linkages and connections Cooke explores in his poetry speak to the existence of a human commons spanning time, politics and cultures. This elucidation of what is shared rather than what differentiates is politically meaningful, since to confront global environmental crises such as climate change will necessitate the adoption of an integrated global vision. He writes:

as if f

alling spirits weren’t caught by anyone but picked

up from the plain by hard white hands it’s

hard to talk about the dry, about what

what should or shouldn’t be […]

Now (here comes the rain)

with a capacity for change only time will tell la

vida derecha echa la echaste (trust) live

the drought, eat bad rhyme. Shout: Give back the land!

My hair’s too thin to mimic a downpour (‘Sonnet to rain [Son al silencio]’)

In addition to geological and biological connections, Cooke recognises a commonality of histories, in terms of the colonisation and repression of indigenous peoples and the need for acknowledgement of these histories in poetry that speaks of place. The colonisation of Aboriginal peoples in Australia and the Mapuche communities of Patagonia share many parallels. Cooke is one of many contemporary poets exploring the potential of poetry to articulate visions of the landscape that are not regurgitations of the colonial perspective, but instead embrace the vast spectrum of human and non-human cultures. As he explains in a recent article in Landscapes, Cooke’s poems embody the recognition that any trans-cultural poetic vision taking an anti-colonialist stance must attempt to eschew Western visions of categorisation and subjugation and strive for multi-vocal expressions of a complex location. Using both his significant experience with indigenous communities and extensive reading of indigenous poets both in Australia and South America, he writes from a place that values indigenous perspectives, allowing this way of seeing to sit alongside an ecological understanding of place in his work. Cooke’s poems reflect the profound understanding that for Aboriginal people language arises out of and in response to Country and, as a natural consequence, language is an inseparable component of Country.

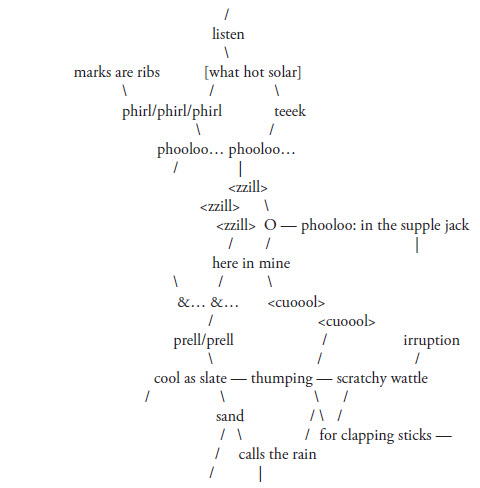

Cooke’s work becomes truly innovative when it recognises and explores the intersection between landscape, ecology and language. Cooke forges an entirely new syntax in his attempt to pull together and collate diverse material and experience from geographically and biologically varied locations. While creating his version of a transcultural poetics, in several sections Cooke frees the words or symbols from the need for communicating meaning, and instead invites them to act on the page and to provide texture in a sonic or graphic sense, which Peter Minter has written about this in his 2012 article, ‘Writing Country: Composition, Law and Indigenous Ecopoetics’. The poems ‘Biophilia’ and ‘Lurujarri’ both contain numerous examples of this. This is language as ecology and ecology as language. Cooke experiments with Jill Magi’s premise that, much as life evolves from non-living matter, so too can linguistic communication evolve from non-semantic sounds. For Cooke, language is a living system and such words and symbols can carry far more than their semantic value. ‘Lurujarri’ is a long poem in nine parts in which Cooke documents his experience of Country in the West Kimberley region of Western Australia. It is figurative, lyrical and experimental, with Cooke expanding the boundaries of language to represent a visceral experience of place. The physical, visual and aural landscapes are all rendered into text:

(‘Lurujarri’)

References to grammar and syntax proliferate in ways that speak to Cooke’s thinking about language as ecologically fertile. The profusion of grammatical terminology, alongside and combined with landscape imagery, brings to mind the role of sexual reproduction in genetic diversity and evolution. This reinforces what I perceive as Cooke’s thinking about language as part of Country as it seems to function ecologically in the poems, much like energy flowing through living systems. Lines of Spanish erupt in poems sporadically throughout the collection, reinforcing the idea of multi-layered connections between Australia and South America. While I spent some time checking my Spanish translations, I found it well worth the effort, particularly as it sparked thinking about the role of translation in linguistic connection and the writing of place. (Is literal translation important to the poems or is it more significant in its symbolic representation of another layer of cultural synthesis between these two continents?)