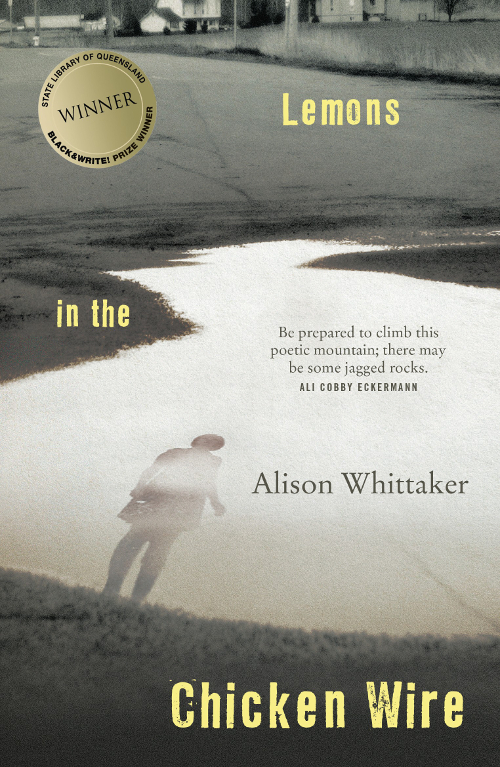

Lemons in the Chicken Wire by Alison Whittaker

Magabala Books, 2015

Gomeroi poet Alison Whittaker’s debut collection Lemons in the Chicken Wire is a necessary addition to contemporary poetry. Deftly handled at both the level of the poem and the book, Whittaker’s work introduces us to the worlds of queer Aboriginal women living on the rural fringe of New South Wales. The first half of the collection comprises poems very precisely located in this rural space and in that of adolescence. In ‘The First Coolest Thing’, Whittaker’s powerful use of repetition invokes ghosts of Gwendolyn Brooks’ ‘we real cool’. Its opening stanza is uncomplicated:

if she’s wearing thick lip gloss you’ll feel it on your face when you’re on the bus for hours back to your nan’s place

But the poem takes us to a far more ambiguous ending:

if she’s wearing fists you’ll feel it on your face when you’re on the dole and-shamed-and back to your nan’s place

Whittaker’s is a visceral poetics, calling to mind feminist literary theory on the intersection of the female body and aesthetics, especially in terms of the role of the wound or the bleeding body. This context meets with the queer aspect of her work in fruitful ways. In The Promise of Happiness Sara Ahmed defines the moment of queer pride as ‘a refusal to be shamed by witnessing the other as being ashamed of you’. In ‘Carry the One’ pride appears in the matter of factness of: ‘I carry the one / and Aunt Mary’s last devon roll / first blood from my uterine walls / I wait for ‘e so I can come’. In ‘Whatcha’ the ventriloquism of an elder family member becomes a direct act of witnessing: ‘Whatcha bleedin’ in the bath for, girl? / Don’t kid me, I can see it / See, there, a clot near the drain ‘ole / And your cunt pashed the rim while you were shavin’’. These recurrent images of menstruation are tied to the erotic, as in the sparse poem, ‘-ing; ‘ly’, which plays with the eros/thanatos binary in startling ways:

I sucked her fingers one by one where I lingered, rings of lipstick stayed on one knuckle, then another hot and red and suddenly sticky like a surprise cut red marks like keen slices as if she moved them, presently they would split at the joint like a doll whose ball sockets rotted dislodge into my throat gut and choke me instantly

As the collection develops in the second half, Whittaker begins to trouble and deepen the themes of these early poems, directly speaking to and integrating various literary, postcolonial and epistemological theories. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick states in Tendencies that queer is ‘a continuing moment, movement, motive – recurrent, eddying, troublant. The word ‘queer’ itself means across. Whittaker’s academic work at the University of Technology Sydney is concerned with postcolonial Indigenous epistemologies and their relationship to the criminal justice system; her poetics go across these areas, extending beyond them. In ‘The Double Mirror’ she layers the postcolonial theory of Sara Suleri with a racist encounter:

Suleri said the colonised

(in humid rooms, plucking affray socks from low slow-cutting

fans)

Whittaker then shows:

(myself watching him watching me, he stifles a grin and takes a

photo)

she said we now had no eyes or tongue. In the squinting light, our

calcified history

(I wonder where it goes, who he shows

The Bus Bitch/Lardo/Coon.jpg)

demarcated, cannot rescue us from the gaze of another

(I put lipstick on for this shit?)

What is remarkable, and displays the precision of Whittaker’s craftsmanship, is how the different registers in this poem are in balance. Similarly in ‘O, Eureka’ the speaker establishes a relationship between the wisdom of Descartes and their Nan:

And O, the first time I said a long white theory word she yarned stiff to impress me … And then, at every drawn goodbye like a choir, leaning each to the other to hold a clap my nan clasps my hands and whispers to me decolonising epistemology, and critical autonomy, and affective phenomenology. And what she says is: remember yourself, and call me once a week on which I ruminate O, Eureka!

In ‘The Double Mirror’ and ‘O, Eureka’, the common wisdom of when to wear lipstick or the advice of Nan is treated as a knowledge base equal to the theoretical.

In an interview with Tincture Journal, Whittaker writes that she:

wanted … to mimic the interaction between world and mind, and represent, in some small way, how colonisation dislodges meaning-making, language, self.

In the first half of the book Whittaker disturbs language through the aforementioned techniques of repetition as she shifts between very regular and suddenly syncopated prosody. In the latter half of the collection, as in ‘The Double Mirror’, Whittaker collages and adopts other nuanced formal experimentations, as well as engaging directly with the Gamilaraay language to attempt a decolonising poetics. Disruption of form and language also occurs in the overall layout of the collection. Many poems have incomplete or opaque titles (‘-in;-ly’ or ‘Re- ; In-’, for example), and Whittaker omits the conventions of a contents list and page numbers. These are processes by which the collection subtly resists the reader.

There is also a sting to these poems. Whittaker uses humour and wordplay in similar ways to the English poet Stevie Smith, whose simple prosody of hard rhymes and excessive repetition accumulate to create a sense of the uncanny. A triptych of poems concerning funerals is threaded throughout the book, distilling Whittaker’s concern for what she has called, in her essay ‘The Aniseed Terminus’: ‘[t]erminal Aboriginality’, an ‘accumulative mourning that leaves its hot stench in the air’. A morbid humour occurs because the ‘daily instalment of sadness dampens the eruption of grief at a new death each week, it allows mourners to chuckle at the sight of three ambulances at a funeral and a cousin tearing at the casket’. In ‘A Funeral’ the speaker’s grandfather is buried: ‘He had a summer funeral and we all wore short skirts / I could hear him whisper “skanks” as the ribbons wound him down. And / when a little cousin put soft serve on his coffin / we heard, through tears / “He’s lactose intolerant, you cunt!”’. Likewise in ‘Preface: Another Funeral’: ‘Uncle tripped over, twisted his ankle and tried to sue. / a couple deep in sleep in boxes’; and in the devastating ‘Epilogue: A Funeral’, ‘even the white stencilled cross makes you wither with her scowl / her forget-me-not fake lillies / “Don’t you fuckin’ forget me or forget to feed my dog!”’. These communal scenes and Whittaker’s use of vernacular language echo Ali Cobby Eckermann at her most powerful.

In a recent blog post for Meanjin, Whittaker questions the intersection of ‘bad poetry’ and ‘Aboriginal Women’s writing’:

criticisms of Aboriginal women’s poetics strike deep to their poets; their contexts, their motives. In the canyon between life and national politics in Australian writing, the poetry of Aboriginal women has offered its back as a bridge (or has been co-opted into one).

She continues to say that she has:

read and written Aboriginal women’s poetry that is unabashedly sentimental and in equal parts and without any contradiction, intellectual. ‘Bad poetry’ gave me the guts to write bad poetry.