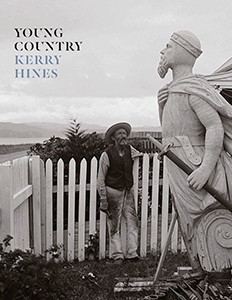

Young Country by Kerry Hines

Auckland University Press, 2014

The relationship between Australia and New Zealand has often been characterised as one of sibling rivalry, between an older and more established nation and a younger and less populous country. As the Honourable MP Phil Goff has commented, it contains ‘the closeness and the rivalries, the expectations and the tensions this implies.’1 To stretch the sibling metaphor further, it seems that the older sibling looms large in the younger sibling’s imagination but the interest is not always returned.

It is a commonplace to say that New Zealand is a ‘young’ country but it’s true, comparatively speaking. In Young Country Kerry Hines has written poems that test, draw and build on readings of an archive of photographs produced by William Williams between 1882 and 1891. Williams was active as a photographer in New Zealand for six decades. His work with the New Zealand Railways allowed him to travel around the country exploring remote regions. He also had a passion for camping, walking and canoeing which gave him access to sites that were unseen by most urban New Zealanders. His work was widely seen during his lifetime and continues to be used to illustrate a range of publications and historic site displays, yet Williams and his work are not currently well known. Certainly the publication of this book will raise his profile, along with that of the author Kerry Hines.

Young Country began as a PhD thesis at Victoria University in Wellington and has subsequently been adapted for publication. There are four sections: ‘The Old Shebang’, ‘Never far from water’, ‘Settlement’ and ‘Whakaki’. Hines began the project with the intention of engendering a ‘co-medial’ relationship between poems and photographs – that is, a relationship in which photographs and poems are presented as equals, the integrity and autonomy of each is maintained, and the co-presentation offers more than the constituent parts on their own. The juxtaposition of image and text on almost every double page means that we are reading one minute and looking the next. Hines’s poetry is ekphrastic in the sense that it is responding to, and amplifying elements from the archive of photographs but never explicitly describing them. As she intended, there is a more nuanced, glancing relationship between the two. Although the photographs may be the starting point for the poems, they never over-determine the images, leaving much to the imagination. The poems often contain disparate narrative threads that Hines deftly weaves together, as in ‘After The Flood’ that contains two separate stories. This poem was inspired by the flood that overwhelmed the Hutt Valley early in 1890. Due to the failure of this township, the settlement was relocated to its current site in Wellington:

Over our heads, debris in the trees. The Hutt, people said Run for your lives. That was how Wellington got started.

Section one of the poem introduces the flood while Section two moves onto the story of a man who sets his house on fire and the subsequent court case, told from the point of view of his daughter: ‘The case was thrown out; he aged ten years. / Fourteen witnesses. No hard feelings. / The banks of his life undercut.’ Faced with these two stories, the reader can draw a connection between the natural disaster of a flood and the personal crisis of a man whose life has been destroyed through his own impulsive actions. According to the notes at the back, this poem was inspired by the apparent arson committed by Williams’s father-in-law.

Although the viewer has no access to the ‘real’ Williams, he comes across as a seeker; a curious person who was trying to make sense of his new home. Born in Cardiff in 1858, he moved to New Zealand in 1881 at the age of 23. As Hines points out, his photography betrays an awareness of what constituted ‘a good view’, with many of his photographs being close to the work of contemporary photographers such as Burton Bros. and F A Coxhead. Yet there are other images in this volume that reveal theatrical and even experimental qualities. The photographer himself appears in some of the photographs that were taken at his early lodgings in Cuba Street, Wellington, which he shared with two other young men, T H (Tom) Wyatt and Alexander Barrington Keyworth. Their house was known within their circle as ‘The Old Shebang’. In a photograph of the same name, the three housemates strike poses while doing quotidian tasks in their backyard: cutting kindling, reading, collecting coal. In another image from 1883, Elsdon Best – later to become a noted ethnographer – and Tom Wyatt are dressed in mock Maori dress at The Old Shebang, as if they had ‘gone native’. The note to the photograph tells the reader that the same men joined the Armed Constabulary a few weeks apart in 1880 and may have served together in Taranaki, a site of conflict during the New Zealand wars.

The early landscapes of colonial New Zealand as recorded by Williams are stark, lonely and haunting. They emphasise the sheer slog involved with creating a nation out of the bush. In the late nineteenth century, the work of clearing trees and ‘breaking in’ the land was seen as central to the process of building a nation. The pioneers, who cleared the dense New Zealand bush appeared to commentators as cast in a heroic mould, equivalent to the American frontiersman and the Australian stock-drover or selector. Historian Keith Sinclair notes that it was believed that breaking in the land required a superhuman effort that inevitably formed the national character.2

In Young Country there are numerous photographs of clear-felled terrain as in ‘Land cleared of trees at Titahi Bay’ (1880s). Williams has captured landscapes in rapid transition as they were cleared in preparation for the infrastructure of Pakeha occupation. On the domestic front, the image of Mrs Lydia Williams using a rake on her land in Napier (1888) shows what a rough and ready place it was, seemingly just a mass of wild undergrowth and flooded ground, resistant to efforts to create a manicured garden. In ‘Settlement’ a woman’s walk down a local street is described in tangible detail:

She hesitates before she takes that road, a cross country ramble through the meaner houses. Tiptoeing mud, side-stepping sludge, trough, puddle and waste.

Viewing these images I found myself admiring the determination of the early settlers while harbouring an uneasiness about the fate of the first people they had displaced. As Alex Calder observes, ‘Pakeha are not only relative newcomers and strangers but also beneficiaries of the historical marginalisation of Maori.’3 They enjoy the fruits of the land and the wonders of nature at the expense of the prior inhabitants. Maori are represented in a number of Williams’ images, including ‘Digging a drainage ditch in Whakaki’ (1889) in which Maori men in traditional dress are digging furiously with white overseers standing above, giving orders.

Despite the tangible and continuing presence of Maori, most New Zealand poetry from the late nineteenth century accorded with the widespread belief that New Zealand was an ‘empty’ land, which has its counterpart in the Australian myth of ‘terra nullius’. In one of Blanche Baughan’s poems she imagines that the country had no monuments or graves: ‘Here at the end of the earth, in the fact of the Future, / Thou standest, a country to come! / Thou art not defiled with the dust of the Dead.’4 Visiting writers such as Mark Twain and Anthony Trollope were a major source of knowledge about the colonies: they both reflected the nation back to itself and exported intelligence of Australia and New Zealand to the Old World. Hines’ poem ‘The Author in New Zealand’ concerns the tour of the colonies by Professor Robert Wallace of Edinburgh University with ‘the object of observing the methods of farming and stock-raising and the peculiar characteristics of colonial agriculture.’ He ‘proceeds northerly’ through the colony from Whakaki to Broken Hill, emphasising the interrelated nature of the two colonies. The expert’s every word is hung upon by the locals who desire reassurance:

And yet his praise Freely given but not lightly meant. The best sheep country that the writer has seen In any part of the world. The shepherd’s daughter stands Intrigued: we’re to be A chapter –

Indeed, Wallace’s Australasian research was duly included in The Rural Economy and Agriculture of Australia and New Zealand (1891) with accompanying photographs of Whakaki station by Williams.

When confronted with historical displays in museums, I find myself ‘othering’ the early pioneers, seeing no connection between their struggles and my own. This book reminded me of the human traits that we have in common with these predecessors – humour, curiosity, desire, incompetence. ‘The Man Who Tried To Kill Himself With An Axe’ features a drunken man who couldn’t see the job through: ‘His problem was impatience / it’s the wrong physiology – the doctor/ demonstrated – inefficient from a muscular-skeletal point of view. / The jury was not unsympathetic.’ In another poem, ‘The Man Who Lived On Beer’ we learn ‘the man who lived on beer / lay in bed, and thought of carrots.’ This character had his origins in a Wairoa resident who tried to prove that it was possible to live on beer alone, with fatal consequences.

- Phil Goff, ‘The Trans-Tasman Relationship: A NZ Perspective’, The Drawing Board: An Australian Review of Public Affairs 2.1 (July 2001), p. 1 ↩

- Keith Sinclair, A Destiny Apart: New Zealand’s Search for National Identity, Allen & Unwin, 1986, pp. 8-9. ↩

- Alex Calder, The Settler’s Plot: How Stories Take Place in New Zealand, Auckland University Press, 2011, p. 4. ↩

- Blanche Baughan, ‘Maui’s Fish’, The New Place: The Poetry of Settlement in New Zealand 1852-1914, ed. Harvey McQueen, Victoria University Press, 1993, pp. 211-212 ↩