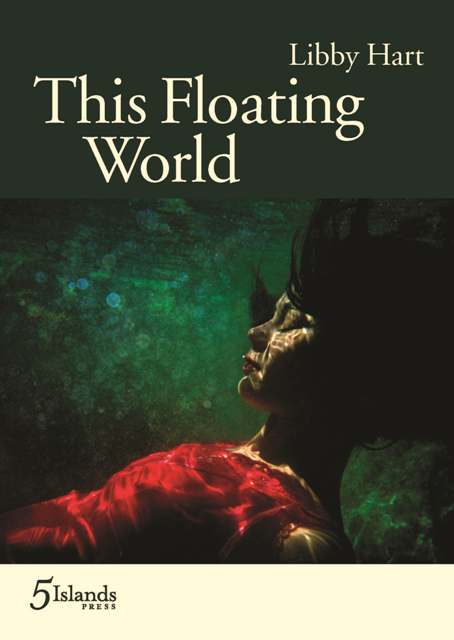

This Floating World by Libby Hart

This Floating World by Libby Hart

Five Islands Press, 2011

This Floating World is Libby Hart’s long-awaited follow-up to her 2006 Anne Elder Award-winning Fresh News from the Arctic. Like Arctic, the collection is heavily dependent on both the natural world and the nature of humans in relation to that world. I am making an educated guess that the book is a product of Hart’s residency at the Tyrone Guthrie Centre in County Monaghan, Ireland, as the structure of the second and major part is a songline of the area. From what I glean, Hart went to Ireland, fell in love with its extremities, saluted the wind again and again through a measured and responsive verse, dreamt of what the ocean might say, spied on lone figures, imagined their thoughts and longings and gave them voices. I love the concept. A map would have given readers a worthy visual, but I am willing to set aside the issue as it could well have been an aesthetic choice and, truly, the poems as maps speak for themselves.

The book is made up of two sections, though it is the second section – the songline – that feels central. I’m not entirely sure why there are two sections, unless there is something private going on in the layout. It would appear that in the first section, made up of only four poems, Hart is the ‘I’, perhaps writing personally to her lover, whereas the second section is made up of other voices: a homeless man, a bus driver, the wind, a dog, the rain. As the second section is so pointed and purposeful in both structure and intention, the first section doesn’t serve the collection as a whole. Incorporating the poems within the songline (there would have been sneaky ways to go about doing this) or even saving them for another collection would seem a better option. That said, I choose to focus on the second section.

As the term songline suggests, Hart takes us on a journey through Ireland. It’s not a very geographically focused songline, as it criss-crosses the island and finds the traveller retracing footsteps to get from one point to the next, so one should not lean too heavily on the songline as physical connection. Hart’s songline is an emotional connection, and she is so connected, so utterly attuned to her environment, that it is enviable.

One way in which we see this connection is through extreme repetition. Throughout this book there is a lot of movement forward, a lot of hands (even hands moving forward) and a great deal of waves, wind and rain. Love is fundamental, as is the isolation of man, and that isolation is best portrayed when set in relation to natural forces. She writes in ‘Lover’:

I’ll remember my legs looped at your hips

and how the weight of you held me down.

Otherwise I’d float in the rafters calling your name.

And in ‘Fisherman’:

Here they come, rolling in like thunder.

All written in cloud, all sluiced in wave.

Here they come.

These waves and thunders connect the people of Ireland, and that makes the setting of Hart’s poems come alive for readers; but what is really exceptional is how this local connection comes across as a universal connection. There’s a subtlety and tenderness with which Hart speaks to us that allows for the local to be translated into the universal, which in turn allows us to relate to the poems even we have never been to, for instance, Ballyshannon, a town in County Donegal, Ireland. In ‘Lone Figure’, for example:

I looked out towards O’Hanlon’s Hill

and the world felt very small

as if I could put it in my pocket,

rub it like a polished stone.

As typified in the chosen stanzas above, there’s an everydayness to Hart’s language; it’s not in any way difficult to make sense of her lines. The simple, however, is made complex not through grandiose metaphors or pretentious words (grandiose and pretentious being fine examples of words to which Hart would probably not pay much mind), but through understated imagery. It’s the sort of delicacy that a poet can’t necessarily practice as a skill; the poet needs to find it within herself. I felt I was reading something very emotive; the cerebral didn’t even come into play. I felt I was reading something extremely personal to the poet, and I therefore felt that Hart’s time in Ireland was incredibly inspirational to her. It is a beautiful talent for a poet to pass on her own inspiration, fully formed yet completely unassuming, and for the reader to connect with it so that the foreign at once becomes familiar. In the poem ‘The rain, speaking’, for example, Hart does not use any words. Her language is repetitive symbols of raindrops. And we feel her connection to the rain; we hear her speaking through the rain; we hear the rain speaking.

My advice to Libby Hart is to keep on writing in this way so that people with money will continue to provide her with the means to travel. I would love to see what she could create out of some concentrated time away in southern Utah, for instance, or on a small island in the Pacific Ocean, or in South Africa among shantytowns. The world awaits Libby Hart.