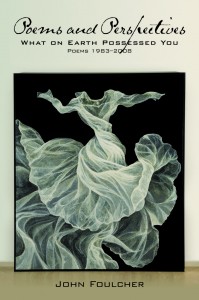

What on Earth Possessed You: Poems 1983-2008 by John Foulcher

What on Earth Possessed You: Poems 1983-2008 by John Foulcher

Halstead Press, 2008

I read the first three quarters of John Foulcher's What on Earth Possessed You: Poems 1983-2008 in one sitting, without picking up my pen. So enraptured was I with these twenty-five years worth of collected poems and a handful of new ones that I ignored my call to duty as reviewer in those first fifty-one pages, avoiding even mental notes, because I didn't want to break the seamless stream of one poem to the next. Reading poetry that consistently flows is truly a rare treat. Poetry is often a complex beast dressed in radiant robes, so usually one stumbles over a jolt in rhythm or a difficult word or some obscure detail pertinent only to the poet. But Foulcher's poetry feels natural, and it feels right; hence the flow.

Foulcher is an imagist. The 'Perspectives' section of this book will tell you this, but you only need to read the first few poems to determine it for yourself. Foulcher takes a moment and draws it out so that a story unfolds, allowing us not only to see the moment, but to sense it, as if it has happened, is happening, to us. I think his success lay in the conversational style he uses to show us these moments and characters. He talks to us in plain English. There is no extravagance in his language, only a clarity of word choice and a deftness at stringing the words together. The everyday-ness of his topics (such as chopping wood or swimming) makes the image that much more precious, because it points to the wonder that is simply a lived life; though he also captures war, religion and death with a faultless ease. The five page poem 'Living' not only brought tears to my eyes, but those tears fell quickly, wetting and warming my cheeks in a confusion of sadness and comfort.

In her eyes, something is leaving,

the way you'd focus

on a bird in flightthat's clear for a moment

then merely form, diffusing into colour.

It is fair to say that nearly every poem in the collection has a few perfect lines, or a perfect metaphor or simile; but for me the book seems to unravel with 'The Present Frame of the World'. In this poem, Foulcher takes an abstract concept and grapples with it in no concrete terms. The poem is from Convertible, which was published at the turn of the millennium, so perhaps Foulcher was wrestling with meaning in a technologically changing, ideologically conflicted world. Then another shift in his selected poems from The Learning Curve, where imagism is traded in for experimentation in voice, in order to capture the mood of the schoolyard. I skimmed through these, completely uninterested, and eager to return to his quiet, more subtle revelations, which I hoped would be revealed in his new poems. Though I am utterly disappointed in 'The New Cathedral', where Foulcher, again, ignores the concrete and invokes a surreal presence to explain away our modern world (which, I am sensing, rather frightens him), I was relieved when I read the final poem, 'Photographs the Size of Poems'. In it, Foulcher revisits his father, once again unfolding his stories and his illusive character through a series of images:

In my dream it's snowing, the air's like ash

and your breath looks like smoke. Wind

makes artistry of the cold, daubing flakes

of ice all over the lens. I wipe them away

but they come back, they're multiplying,

dividing, like cells under a microscope.

The cold gets colder, freezing your face

into an oval miniature, glistening, out

of focus, the camera shaking in my hands

and the snow coating everything white,

there's nothing but white in the frame.

I wake in the dark calling Smile, Dad. Smile.

It is a perfect ending to the collection, assuring me that the style which had captured my emotions so succinctly at the beginning of the book had not been lost to a new millennium or a man grown older, perhaps tired with the seemingly mundane in our lives.

In the book's stunning introduction, simply titled 'A Word from the Poet', Foulcher explains the book's structure by referring to the critical responses to his work by Geoff Page, Jeffrey Poacher and Robert Gray works to 'acknowledge the reader's critical intelligence by offering a number of ways of looking at the poems'. But he also points out that these critical responses run the risk of ruining poetry's primal effect on us.

I don't see how the critical evaluations can ruin anything, however, if one doesn't read these perspectives first. What these critical responses do is point the reader in the direction of a possible second reading. Armed with the opinions of practiced critics, the reader may wish to revisit the collection from a different view. I think it is a worthy risk Foulcher has taken, but only because the book spans twenty-five years and is a selected works. This sort of structure would seem entirely inappropriate following a single collection. But in the case of What on Earth Possessed You, I think it makes sense. In choosing the poems for this selection, Foulcher has sifted through a long career of works representing specific times in his own private history, imprints of his memory and significant reckonings. Why not conclude with others' perspectives on his own perspectives, summing up his career thus far in a way that is distanced from Foulcher's personal life reflected in his words? It suggests a bigger picture, carving out a specific space in the realm of poetics for an entire body of work, rather than allowing the poems collected in a single book to represent a poet's career. Some may vehemently disagree, quoting Foulcher's own words in his introduction, 'Poetry's a free thing, always, despite the attempt to contain it', but debate, if anything, sells.

Heather Taylor Johnson holds a PhD in Creative Writing and is a poetry editor of Wet Ink.