Object Permanence by Toby Fitch

Object Permanence by Toby Fitch

Puncher & Wattmann, 2023

The Inclination Compass by Gareth Sion Jenkins

Puncher & Wattmann, 2023

Toby Fitch’s Object Permanence: Calligrammes (Puncher & Wattmann, 2023) and Gareth Sion Jenkins’ The Inclination Compass (Puncher & Wattmann, 2023) both represent not only the culmination of large bodies of work, but also can be considered avant-garde in their experimentation with the boundaries of poetry as a visual medium. Taken from the French term for advance guard or vanguard, the avant-garde is, by its very definition, always out in front, pushing ahead, self-consciously, even egotistically, leading the way. Yet, over one hundred years after the emergence of modernism, the term avant-garde has become problematic in numerous ways. Although compounded by the passing of time, a paradoxical desire to break with the past in favour of the radically new, even as this very newness is seemingly defined by repetition, has always been at the heart of avant-garde experimentation. To alleviate this problematic, A.J. Carruther’s has preferred to refer to contemporary Australian poetry that is radically experimental as either neo-avant-garde and then, increasingly, as “experimental poetry,” even describing Fitch’s work as “post-vanguardist” (Contemporary Experimental Poetry in Australia: Tendencies and Directions, 2017). However, in their desire to surmount the separation between visual and linguistic, the compartmentalisation of space and time enforced by our sequential written form, the aims of these works can be seen as, in some sense, classically avant-garde.

Puncher & Wattmann’s expanded edition of Object Permanence brings together over a decade of experimentation with a form of visual poetry that has become Toby Fitch’s signature: the calligramme. This is a form of poetry whose words are typographically arranged to create a visual image that contributes to the meaning of the poem, made famous by Guillaume Apollinaire’s 1918 collection Calligrammes. In ‘Object Permanence: How does the calligramme take shape?,’ an essay that also stands as a manifesto of sorts for his explorations with the form, Fitch has written a micro-history of the calligramme, briefly tracing the roots of this visual form back to ancient Greece and through the medieval period. However, Fitch’s greatest visual influences are the moderns: the French symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé and, particularly, avant-garde provocateur Apollinaire. This influence is strengthened further by Fitch’s repurposing of textual fragments throughout the collection from a range of symbolist and modernist poets, though he also combines these with allusions to the mythical, the contemporary, and the mundane. A further element Fitch adds to his calligrammes, collaborating on design and typesetting with Chris Edwards, is colour. Inspired by modern internet culture and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Theory of Colours (1810), the collection’s often gaudy, fluorescent colour schemes emerge out of a black background, adding a further visual layer to the poems that shapes their meaning.

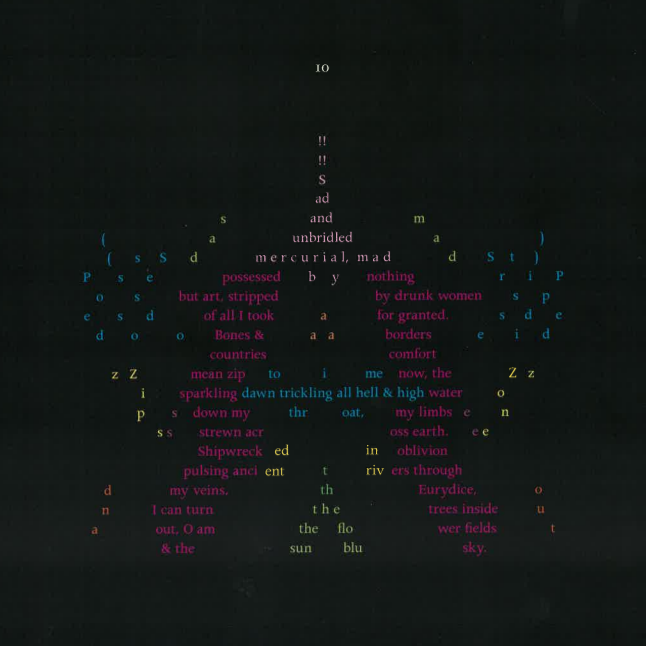

‘Rawshock,’, a series of ten calligrammes, shows how all these diverse elements form a rich textual and visual chemistry within each calligramme (n.p.).

The poem itself is somewhat opaque on first impression, other than notable allusions to Orpheus and Eurydice. However, Fitch reveals in his ‘Notes’ that the poems not only regurgitate phrases from early-modernist poets (Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Baudelaire, Mallarmé, and Rainer Maria Rilke) to offer a retelling of the ancient Greek myth, but do so using the ten original Rorschach inkblots as templates. Created by Hermann Rorschach, the ambiguous designs of these standardised inkblots have been used for psychological testing. The mythical content of the poems combines with the ambiguous nature of the shapes to provoke and play with how the reader might interpret these calligrammes. Is ‘2’ a gate to Hades? Could ‘5’ be a harpy? Does ‘10’ represent Orpheus being brutally dismembered for what he has seen? By drawing on a myth in which Orpheus is punished for relying on his vision, rather than his faith, Fitch foregrounds the power of sight, even as he ironically employs a textually-stored myth to do so. In many ways ‘Rawshock’ epitomises the problematic Fitch poses with his calligrammes: what we see visually shifts our perception of the story, just as reading the narrative, in turn, shapes how we ‘see.’ Employing myths and textual fragments, Fitch adds further complexity to this hermeneutic feedback loop. ‘Rawshock’ asks provocative questions about the connection between myth and the subconscious, but in a wider sense this series signifies Object Permanence’s underlying interrogations into the nature of perception and reality.

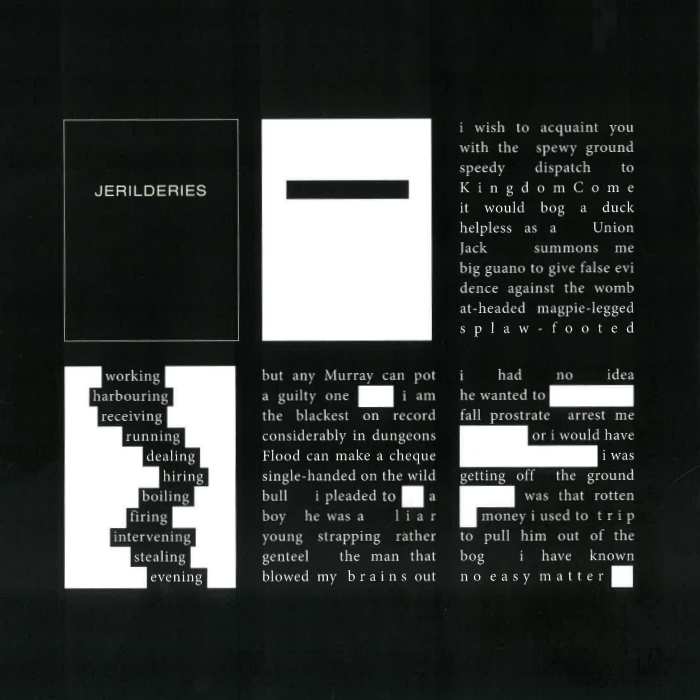

Traditionally the Australian avant-garde has been perceived as lagging behind, but Fitch’s ‘Jerilderies’ calligrammes remind us that sometimes one is so far behind that it can be imperceptible from being ahead. The radical manifesto-style declaration of Ned Kelly’s Jerilderie Letter and its rawness – lack of punctuation and shifting range of registers – led first Peter Carey and then a range of poets to admire its ‘avant-garde’ qualities. Fitch draws on fragments of Ned Kelly’s original letter and creates thirty-five helmet-shaped collages that recall the myth and its iconography:

I found the stark black and white rendering of this series and its simple imagery (recalling Sidney Nolan), among Fitch’s most striking. A glance at the real Jerilderie Letter reveals the level of Fitch’s invention, the fragments he employs from the letter are often no more than one or two words and he re-sequences Kelly’s words in a pastiche worthy of James McAuley and Harold Stewart. A colossal mythical figure, Kelly is therefore already kaleidoscopic in his range of ‘truths.’ ‘Jerilderies’ plays on these elements to collapse and reform Kelly – “a rogue knows nothing about roguery” – into a supra-real figure, recalling that great modernist literary hoax, Ern Malley (n.p.).

There are so many complex and inventive poems in this collection that they all deserve in-depth treatment. For example, ‘PRO ME THE US’ utilises an anagrammatic translation of Rimbaud’s ‘Promontoire’ to build a skyscaper skyline out of text. The ten part ‘Argo Notes’ combines intermixing colour and amorphous shapes with collages from Maggie Nelson’s Argonauts to suggest genderfluidity. Meanwhile, in the form of a red square tilted on its side, ‘Janus’ suggests that thanks to the Anthropocene – “carbon plague of suburbia” (n.p.) – our gateway might be both opening or closing. And then there is ‘Oscillations’, whose winding form and content not only embody both a cyclone and a stormy relationship, but recall Lewis Carroll’s ‘The Mouse’s Tail,’ an early modern calligramme from Alice in Wonderland which Fitch identifies in his ‘micro-history’ of the form. Each calligramme leads the reader down such rabbit holes.

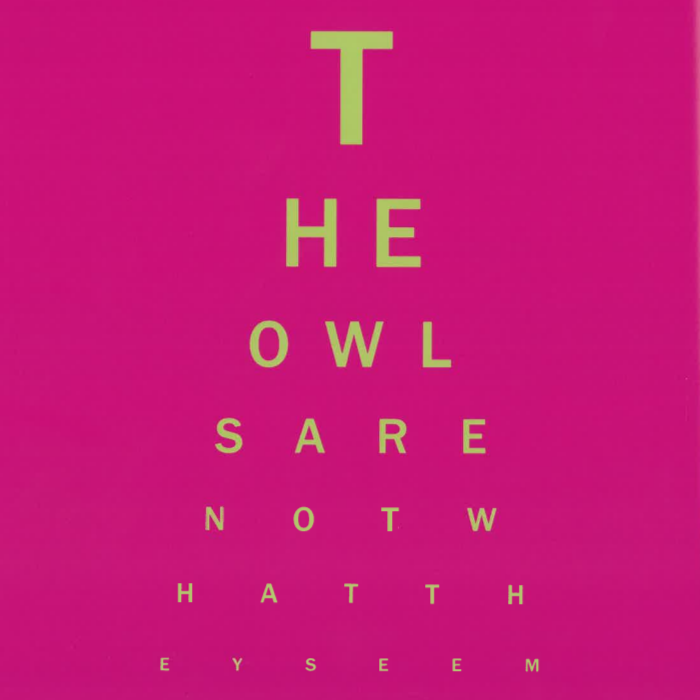

Yet, some of Object Permanence’s most striking poems are its simplest. For example, the series ‘Eye Test 1-4’ visually recalls an eye chart that tests visual acuity, though with a simple message encoded by Fitch:

Detecting the message, despite its simplicity, is not instantaneous and this creates an amusing moment where play is returned to the mundane, making us realise how encoded our ways of seeing and reading are. Of course, as with all of the collection’s calligrammes, there is more than meets the eye: the lines are fragments of dialogue from David Lynch’s Twin Peaks’ surreal red room dream scene, which itself eschews traditional structures of speech. However, it is the fundamental interplay between image and text, grounded in childlike simplicity, that truly captivates and returns the collection’s focus to questions of ‘vision.’

Fitch’s title, Object Permanence, is a psychoanalytic term that defines the point in a child’s psychological development when they can form a mental representation of an object, allowing them to understand that the object still exists even if it can’t be seen. Fitch’s calligrammes play a double trick on us, his poems evoke objects that are not truly there even as they viscerally alter our interpretation of texts that ask us to not see what is not there; instead we must imagine.