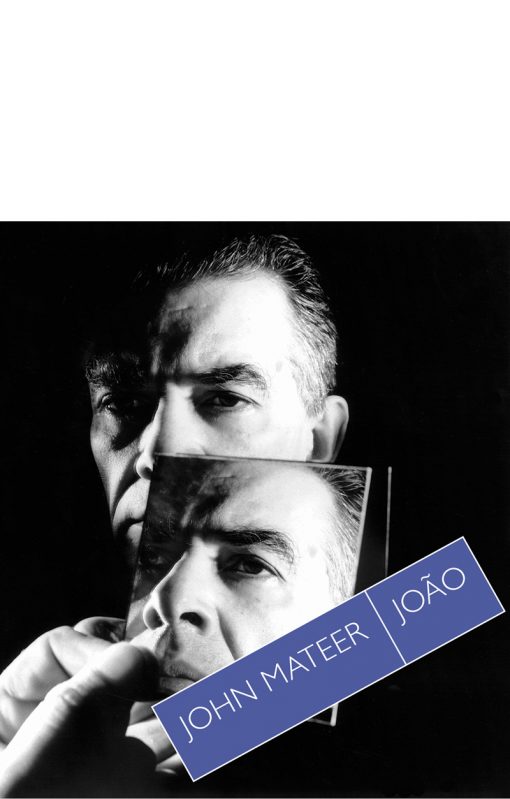

João by John Mateer

Giramondo Publishing, 2018

Of the 62 sonnets that make up John Mateer’s João, 58 are given to ‘Twelve Years of Travel’ and only four to the second and final section, ‘Memories of Cape Town’. This weighting emphasises travel not so much as the mode of exception but as regular or even habituated experience, while suggesting only a marginal place for the ‘home’ of Mateer’s South African origins.

The book’s title suggests trajectories that are personal and cultural. The name acknowledges Mateer’s and João’s matrilinear Portuguese ancestry, and João’s diverse cultural origins. João is the name of a line of Portuguese kings and gestures to European colonialism. It is also the most common boy’s name in Portugal and implies João’s non-identity in a world where travel means vertigo and cultural displacement.

Moving his persona through a series of places and relationships, Mateer affords João few moments of positive connection. Via his travels and an insecure cultural identity João is the ‘Lost Boy’, the ‘young lost poet’, ‘the Foreigner’, ‘the Foreigner!’ He has little interest in his world of literary conferences and festivals, friendships evoke uncomfortable pasts, he enjoys at best tenuous relations with his long list of girlfriends. Where intimacy is concerned, it ends often enough in that staple of travel, separation. In his relationship with Anna, for example, João is the ‘lost and nameless’ ingénue to ‘the more worldly Anna’, ‘who almost loved him’. Love is a near-thing but a matter of loss.

Irony and meiosis, however, inflect the poems’ sense of distance:

They dropped João outside a typical saloon bar for him to find working there the young Brazilian girl, the student who’d offered him a bed. As always João was thoroughly charmed, even with knowing he must wait till she finished work.

The indefinite article and affected syntax (‘for him to find working there’) suggest a chance event, casting João as naïve (or, alternately, calm and unassuming when love seems a sure thing). There’s further irony at a ‘BDSM dungeon’ in Melbourne: ‘Not that, really, / João and his beloved were ever there. Not that her lily-bright flesh / marks up easily, bruises photogenic’, the anaphora highlighting a comic denial. Sonnet 49 tells of a becak driver who wears a Superman T-shirt, and who, in João’s eyes, has a ‘superhuman simplicity’; everything proceeds casually enough until the last lines:

But, in a confusion, João had watched this old becak driver, his near complicity, not being shocked, on witnessing an accident, one man knocked down in the street: how he’d just pedalled past deadpan

The scene exposes João for his dutifully middle class view that the appropriate response in an accident is to assist. Warmer regard for the becak driver gives way to the bathos of a world traveller’s cultural shortcomings and we read on across a shifting affect, with the feeling that João’s next moment of cultural misperception is imminent.

Much of the distance João feels in his perpetual travels is transferred to the reader via this irony and via Mateer’s use of allusion. In his reference to a friend, Josef, who teaches ‘in a morgue’ and keeps ‘Marx’s Collected Works in the library as a memento mori’, Mateer’s appropriation of Marx as a lament for contemporary culture seems clear enough and integral to a poem loosely about societal failings. In other situations allusion seems vague, and for the reader, open; inferential. In Sonnet 44, for example, João and his girlfriend are found by a colleague, ‘mid-argument’ in a park. In the last line João ‘sadly […] remember[s] a statue’s lifted foot, that art.’ The statue remains nameless, the adverb an apparent indictment of João’s caricaturing of a partner who dramatically ‘stamps one’s foot’ or ‘puts one’s foot down’. Significance can seem at once incidental and staged; cultural references are often only, potentially metaphors.

Mateer’s grammar can be similarly obscure: ‘With his new flatmate, João, I should say ‘landlady’, an old famous punk rocker, he might learn more about life.’ And what seem important biographical details are often omitted. João’s ‘beloved’ in Munich faces ‘her own exile’, ‘her own tragedy’, none of whose details are given. As for João’s situation and his corresponding exile and tragedy, these, likewise, are never directly explicated.

In a shifting context that dramatises João’s lack of belonging, travel has a range of implications. If travel conventionally suggests the search for something different in a world of increasing sameness – ‘the body of legends […] lacking in one’s vicinity’ (Certeau) – or release from life’s routines; if it promises the kind of movement that wards off a stasis associable with death; or if it brings us, as it does Barthes at the beginning of the memorable Empire of Signs, the joy of the foreign and of language returned to its sensory substructures, then none of the above resound in João. Travel, rather, becomes an act of perpetual endurance. João finds his middle-class literary milieu tiresome: there is the ‘bespectacled lady […] who had once translated Sophia de Mello, really knowing only Spanish’; João is ‘appalled’ at the fame Rushdie wins by a ‘sporting quip and […] repartee.’ There is ‘vomiting as critique!’ in the millionaire’s garden as the writers ‘go through the motions of being gracious’. João’s world is inauthentic, ‘made-up’, ‘a movie’, ‘cinematic’, ‘a dream’. When Sonnet 20 asks, ‘What João were you doing there’, it feels like a question the reader has been asking throughout. Travel, largely, recedes to the human and psychological dramas it proposes.

Domestic or familial images are scarce and often only further remind João of his detachment from home. To his aunt in Cape Town, he has ‘returned from the Void’. While the boatmen of Capri are ‘stout, sweating […] indifferent to the tourists’, João, on learning that the women following the Flautist in Apollinaire’s ‘The Flute-Player’ ‘were probably whores’, remains ‘the Foreigner, worried they may have been overheard’. These kinds of hyperbolic and comic depictions of the well-travelled and polyglot, but unworldly, João are broken up to the benefit of the collection with moments of more forthright emotion. An example is when João spends a night in Chateau Rouge with a group of Senegalese and leaves ‘the dinner, yearning for Africa, unconfused’. Or, in Mateer’s homage to his friend Goran: ‘Goran, gentle, his speech the kind of warm quiet / that seems an uninterrupted silence, an endless, emancipated poem’. Irony aside, the sudden affect surprises, creating a tonal complexity that needs careful attention.