Imelda, of course, refers to the notorious former-pageant-queen-turned-First-Lady to the dictator Ferdinand Marcos, known for high-shouldered dresses, beehive hair and 3000 shoes. Her edifice complex1 was evident not just in her fashion sense, but Philippine contemporary land and cultural policy. Hastily expedited infrastructure projects in the 1970s reflect a common upper-middle-class anxiety about wanting to present the Philippines as a culturally progressive newly industrialising Southeast Asian economy receptive and equal to wealthy Western countries. In short, a social climbing exercise. This castration anxiety might well be explained by the title of National Artist for Literature Awardee Nick Joaquin’s essay ‘A Heritage of Smallness’, which blamed the Philippines’ lack of economic and cultural prominence solely on the Filipino people’s lack of ambition. As if his own lack of imagination regarding the range of possible causes for the Philippines’ many complex intergenerational messes, was not part of the problem. Nena and her sister, Aurora Bugarin, are maids named in Andy Warhol’s diaries. In Andrada’s poem, Nena and Aurora warn him about the notorious First Lady. They’re not meek or apolitical. They follow their homeland news even from far away. They are citizens – of the Philippines and the world.

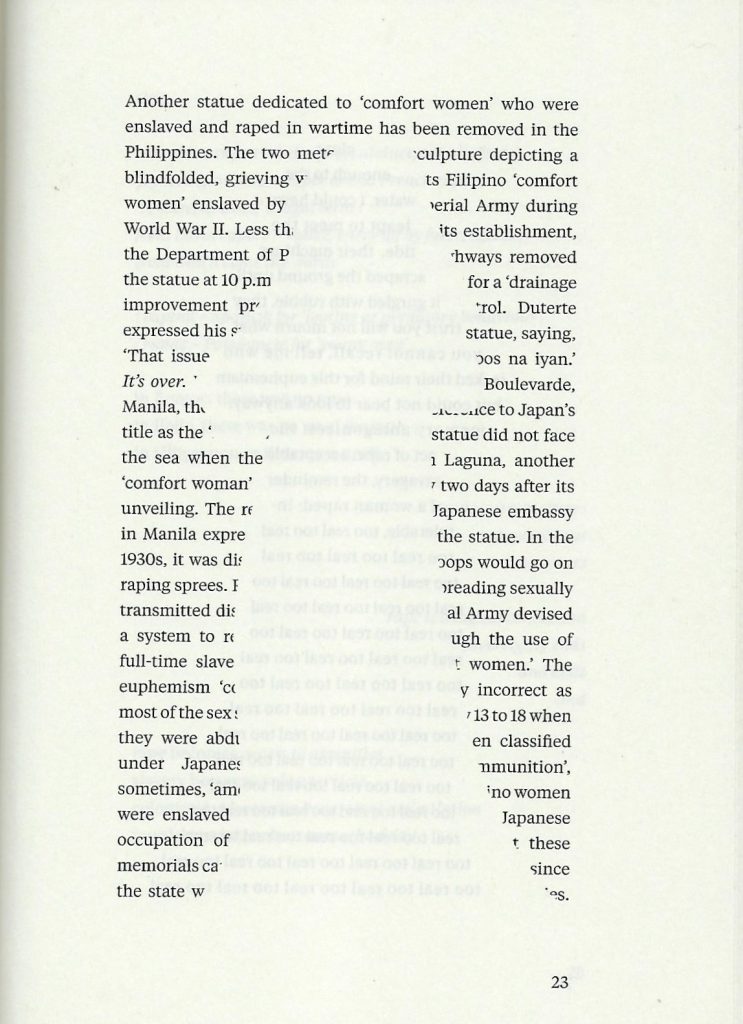

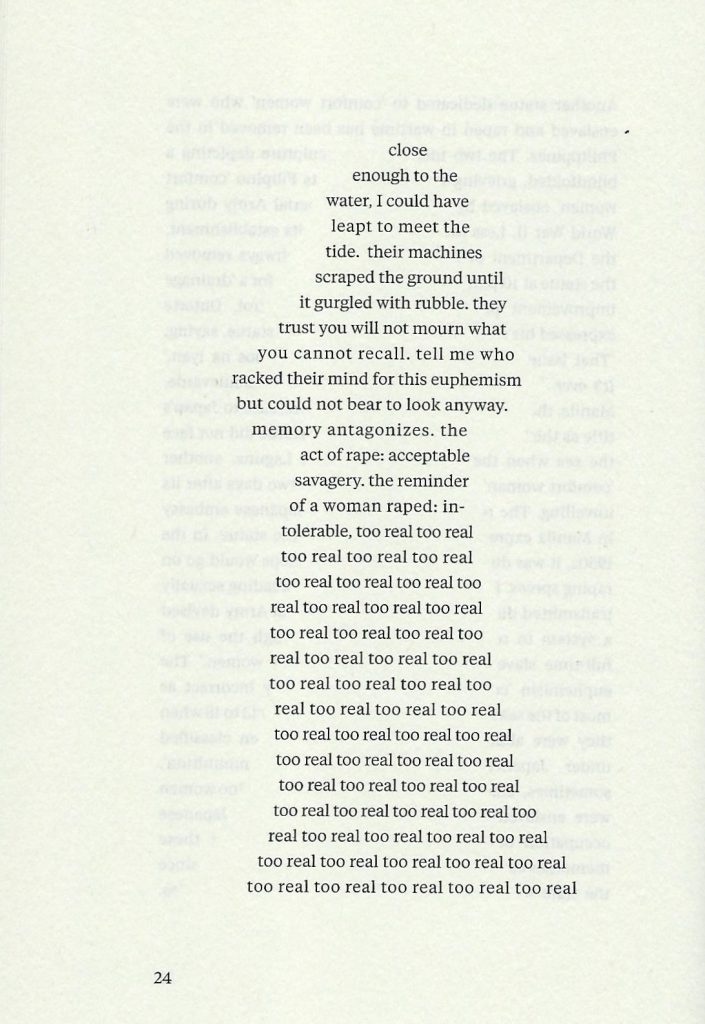

The book is divided into four sections: TAKE:, : COMFORT, : REVENGE, : CARE. Those familiar with twentieth-century Filipino history, either from living through it, or having grown up with these stories in their families, would know that ‘comfort women’ was a euphemism for Asian women sex slaves, including Filipino women, in the territories conquered by the Japanese imperial forces during the Second World War. ‘Comfort Sequence’, the first poem in this section has an empty space in the middle of the verse. The empty space is shaped like the familiar silhouette of a Filipina in the traditional baro’t saya, that visually interrupts a narrative account of how statues built to commemorate the pain and survival of the comfort women, were taken down during the Duterte administration.

The gap interrupts and disrupts both the page and the way this history is told. The existence of the comfort women and their descendants is a reminder of the impossibility of apolitical international relations. The removal of the tributes writes the women out of history, an attempt to wipe the slate clean so the Philippines can (re)present itself as a grateful recipient of aid from its wealthier Northeast Asian neighbour and former invader. The last women who lived through this generation will die soon. They not only risk being written out of time, but also risk being written out of history in the name of economic progress and diplomatic face-saving.

The erasure extends even to peacetime, even to a place as seemingly mundane as an Australian poetry gathering, in the poem ‘Vengeance Sequence’:

The 40-year-old poet who pulled me close and kissed me when I was 17. The poet who came up to me from behind and draped his arms behind me because he just had to. The married professor in his fifties who asked me to send him photographs of myself My bank account will fatten whenever someone tells me their maid, nanny, wife or ex is Filipino I take naps to undo the myth I am hardworking.

Here, the Filipino/a/x poet is among fellow poets, but not among one’s kapwa. Here, the Filipino/a/x poet is treated as an object for violent white possession through acts of unwanted sexual aggression, both in public literary gatherings, and the ways we are written about. In being treated like women who exist solely for the sexual enjoyment of entitled white male artists, we are told we are not and can never be fellow citizens in a poetry community of equals. We don’t get to own our bodies. We don’t get a say in how history talks about us. We exist solely to be enjoyed by white men, condescended to by white women, and have our writing and activism unread and unshared, get lower advances in publishing (if we get paid at all), commissioned only for diversity panels, and dragged into photos so organisations look good on grant applications.

Neferti XM Tadiar writes that the figure of feminised migrant Filipino labour throughout Marcos’s Martial Law years until the present, moved from the ‘prostitute or the mail-order bride to the domestic helper’ and now the nurse – ‘warm body exports … feminine bodily beings-for-others’ who end up raped or murdered by their partners or employers, or murdering their rapists and facing the death penalty in a country far away from a homeland whose government would not fight for them.2 Somehow, those of us who grew up in the 90s and 00s still confront these stereotypes when white people engage us in casual conversations about the Philippines. Intergenerational international political entanglements that began with over 300 years of Spanish colonialism and continued under American colonialism led to the circumstances that make Filipinos feel that we only exist as other people’s toys and tools, not people, definitely not artists. If you’re Filipino, you never get to be writers or artists in the public imagination, despite the objective material existence of many Filipinos all over the world making all kinds of art of a high standard. As unequal power relations are necessary to sustain capitalism, Filipino workers provide social and emotional labour that frees up men’s and middle-class women’s time for rest and leisure, and intellectual, cultural and political action.

- The ‘edifice complex’, after the Oedipus complex, was said to be a word tossed around in the 1970s to describe the Marcos government’s reckless infrastructure investments. Gerard Lico’s Edifice Complex: Power, Myth and Marcos State Architecture (Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2003) explores this in detail. ↩

- The first chapter of Tadiar’s Fantasy-Production: Sexual Economies and Other Philippine Consequences for the New World Order offers a close reading of the news coverage of the abuse, murders and executions of Filipina domestic workers in the Middle East. ↩