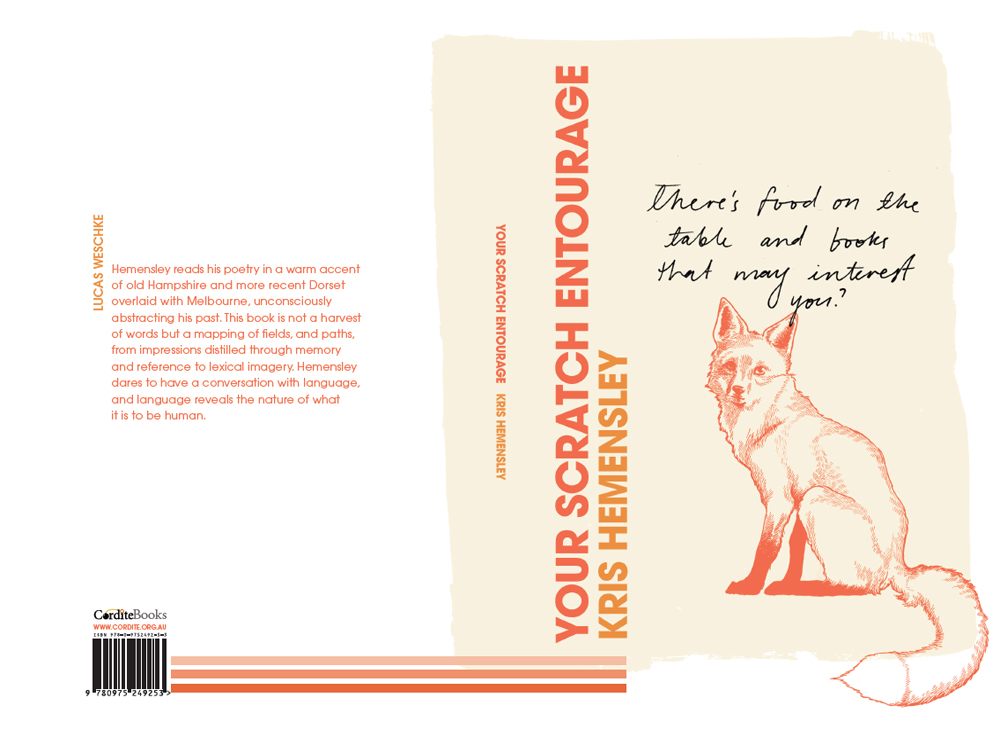

Cover design by Alissa Dinallo, Illustration by Lily Mae Martin

Order the book HERE.

How can one write words about a poet? Last year, Kris Hemensley and I considered Émile Chartier (Alain)’s assertion that ‘men are afraid to complete their thoughts’, on our way to visit Greta Berlin, whom I had first met in Zennor as a small child and whose father, Sven Berlin, had enthralled a young Kris Hemensley in 1963 with the accoutrements of the artist and his first taste of red wine. And down by the harbour in Weymouth, we had already discovered a shared admiration for W S Graham. A framework was emerging.

Hemensley reads his poetry in a warm accent of old Hampshire and more recent Dorset overlaid with Melbourne, unconsciously abstracting his past. The words are uttered to hang as sudden realities on the air. There is an easy intimacy and a careful measure in this, for Hemensley has clearly not rushed the words he has chosen to engage us, and they have come to know their places well. One hears though that the ghost is never far below the surface, as he will break off occasionally to compose himself, his throat constricted by emotion. Apart from a chapbook or two and a CD, it is thirty years since Hemensley’s last collection was published, and one senses that only the combined weight of these new works can have brought them onto the page.

These poems relate to people in their places, and are inevitably auto-biographical, as all art is. They take us into deeply personal territory: the territory of sons and fathers, brothers and lovers; into the territory of war and its enduring shadows. The chapters are stakes embedded in the ground to mark what needed to be acknowledged. This is not a harvest of words but a mapping of fields, and paths, from impressions distilled through memory and reference to lexical imagery, ‘there where the sun catches your shoulder’. In journeys and perspective, nature is drawn as domains not only of sentiment and matter, but also presence and conviction.

Hemensley’s choice of language, form and punctuation is fluid. If fourteen lines are the right vehicle, then good. If an opening parenthesis is required, its complement may not be. Elsewhere running prose sits comfortably in the body of the work. And his characteristic use of the twelve-syllable line is there for the careful reader. Hemensley clearly feels a kinship with other poets, and the trusted place he grants them here has the character of homage. One must recognise that these people have been chosen: chosen by our senses. When Graham told me where the words came from, I did not expect to encounter the same source again. One must recognise that these people have been chosen by our need. The poet is the last artist, using our finest tools to assert that we are not lost, always reaching out to limn that which can only be ‘elicited by the living’.

We are afraid of our thoughts because they lay us bare, and that is how the poet stands, the ‘human witness’ making his or her statement. Hemensley dares to have a conversation with language, and language reveals the nature of what it is to be human. But how else can we complete our thoughts? We choose our brushes, we make our mark, foolish people judge us.